These articles were initially posted on Gants Hill United Reformed Church’s blog in 2020.

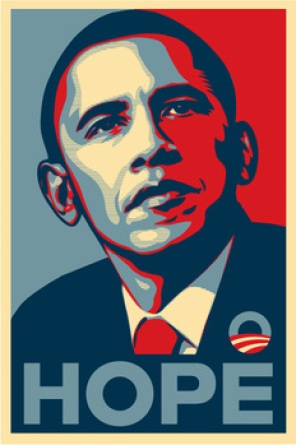

This image has been doing the rounds on social media over the last couple of years. Each named person lived during times when skin colour was more important than intelligence and personality. Whilst racism is nowhere near as bad as it was half a century ago, many people with ethnic backgrounds still face adversity, particularly in the United States. This poster encourages those people to dream, lead, fight, think, build, speak, educate, believe and challenge like the many heroes of the past.

Thurgood Marshall is famous for being America’s first black Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. As well as serving as a lawyer, Thurgood campaigned for civil rights, believing that racial discrimination went against the Equal Protection Clause of the US constitution.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland on 2nd July 1908, Thoroughgood “Thurgood” Marshall learned how to debate from his father, William Canfield Marshall, who worked as a railway porter. At family meals with his father and mother, Norma Arica Williams, Marshall participated in discussions about current events, which fuelled his desire to become a lawyer. Marshall recalled his father “turned me into one. He did it by teaching me to argue, by challenging my logic on every point, by making me prove every statement I made.”

In 1925, Marshall graduated from the Frederick Douglass High School in Baltimore within the top third of his class. After this, he attended Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, where he became the star of the debate team. Marshall involved himself in sit-in protests against segregation and joined Alpha Phi Alpha, the first fraternity founded by and for blacks. During this time, Marshall paid little attention to his studies and found himself suspended twice for his behaviour.

Marshall’s attitude changed after he married Vivian “Buster” Burey (1911-55) in 1929. His wife encouraged Marshall to be a better student, and he graduated with a BA in American literature and philosophy the following year. To become a lawyer, Marshall enrolled at Howard University School of Law in Washington DC, for which his mother pawned her wedding and engagement rings to pay for the tuition. In 1933, Marshall graduated at the top of his class.

After graduating, Marshall began a private law firm in his home town and represented the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which he joined in 1936, in various lawsuits. In one court case, Murray v. Pearson, Marshall represented black students who wished to attend the University of Maryland Law School, which at that time only admitted whites. Not only did Marshall win, but he also created a legal precedent making segregation in Maryland illegal.

At the age of 32, Marshall founded the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which supported many civil rights cases before the Supreme Court. Of these cases, Marshall won 29 out of 32, most notably Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which paved the way for integration in schools. For some of the court cases, Marshall had the support of J. Edgar Hoover (1895-1972), the 1st Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Marshall and the FBI particularly wished to discredit civil rights leader T. R. M. Howard (1908-76), whose policies went against the NAACP. Howard also believed in legalising prostitution, arguing that “man’s sinful nature made it impossible to suppress the sex trade”.

In February 1955, Marshall’s wife Vivian passed away from lung cancer on her 44th birthday. Later that year, Marshall remarried Cecilia “Cissy” Suyat (b.1928), a civil rights activist of Filipino descent from Hawaii. They went on to have two sons, Thurgood Marshall Jr. (b.1956), who was the White House Cabinet Secretary under Bill Clinton (b.1946), and John William Marshall (b.1958), the longest-serving member of the Virginia Governor’s Cabinet.

Marshall’s successful career attracted President J. F. Kennedy (1917-63), who appointed him to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1961. This was a new seat created by the president, which Marshall held until 1965 when President Lyndon B. Johnson (1908-73) appointed him as the first African American United States Solicitor General. This also made Marshall the highest-ranking black government official. Marshall called his position as Solicitor General “the best job I’ve ever had.”

Following the retirement of Tom C. Clark (1899-1977) in 1967, Johnson appointed Marshall as the 96th Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, the first black man to hold the post. When questioned about his success as an African American, Marshall said, “You do what you think is right and let the law catch up.”

Marshall served on the Supreme Court for 24 years, during which time he fought on behalf of black citizens. As well as civil rights, Marshall campaigned for abortion rights and the end of the death penalty. He also fought against anything that made women unequal to men. When Marshall retired in 1991, he expressed the wish that President George H. W. Bush (1924-2018) did not use race as a factor when deciding on his successor. Bush nominated Clarence Thomas (b.1948) to replace Marshall, the second black man to hold the position of Associate Justice of the Supreme Court.

Many accused Marshall of resigning over disagreements with the new conservative approaches of the Supreme Court, but in truth, his declining health was the reason for the decision. Less than two years later, Marshall passed away from heart failure on 24th January 1993 at the age of 84. The Supreme Court honoured Marshall with a lying in state at the United States Supreme Court Building in Washington DC, followed by a burial at the Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

There are several memorials dedicated to Thurgood Marshall, including an 8-ft statue in Lawyers Mall, Maryland. The airport in Baltimore renamed itself the Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport in 2005, and in 2009 the General Convention of the Episcopal Church added him to the liturgical calendar, designating 17th May as his feast day. Marshall’s life is the topic of the 2017 film Marshall, starring Chadwick Boseman (1976-2020) as the first black Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Many people know Rosa Parks as the black girl who refused to give up her seat to a white person on a bus. Even Doctor Who portrayed the story in a recent episode, but how many people know Rosa’s background? How many people know more about her than the bus incident? She is a recognisable name in the Civil Rights Movement, but is that all – just a name?

Born Rosa Louise McCauley on 4th February 1913, Rosa grew up in Tuskegee, Alabama, until her parents, Leona and James, separated. Rosa moved to Montgomery with her mother and younger brother Sylvester, where she lived on her grandparents’ farm and attended the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Rosa’s mother taught her how to sew, and by the age of ten, Rosa had completed her first quilt. She continued to sew while studying academic courses at the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls, making herself dresses to wear. Although Rosa enrolled at a high school set up by the Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes, she dropped out when her grandmother became unwell.

In 1932, Rosa married the barber Raymond Parks, who belonged to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Rosa took on jobs as a domestic worker, but her husband encouraged her to complete her high school education, which she achieved in 1933. A decade later, Rosa joined the NAACP, becoming its first female secretary. For some time, she was also the only female member. As part of her role, Rosa investigated false rape claims against black men and the gang-rape of Recy Taylor (1919-2017), a black woman from Abbeville, Alabama. The Chicago Defender called the resulting campaign concerning the latter “the strongest campaign for equal justice to be seen in a decade.”

Rosa experienced “integrated life” while briefly working for the Maxwell Air Force Base, which did not condone racial segregation. This made her realise the extent of the differences between the lives of blacks and whites. Rosa also worked as a domestic and seamstress for Clifford (1899-1975) and Virginia Durr (1903-99), a white couple who encouraged and sponsored her attendance at the Highlander Folk School to learn more about civil rights in 1955.

To travel to and from work and school, Rosa used public buses, which since 1900 had specific seating areas for blacks and whites. The front four rows were for whites only, and blacks were encouraged to sit at the far end of the bus. Over 75% of passengers were black, which made the rear of the bus very crowded. Blacks also had to use the back door of the bus, but on one occasion, it was too crowded for Rosa, so she used the front entrance instead. After paying, the driver insisted she leave the bus and enter through the back door. As soon as Rosa had stepped out of the bus, the driver sped away.

Rosa avoided that bus driver until 1955 after a long day at work. She did everything right: she entered the bus through the back door and sat in the first row of seats designated for black people. During the journey, crowds of people entered the bus, meaning many people had to stand, including white people. Seeing this, the driver asked those in the first row of black seats to stand up so the whites could sit. Whilst three blacks got up and moved, Rosa remained seated. The driver demanded her to move, and when she did not, he called the police. The police arrested Rosa and charged her with a violation of Chapter 6, Section 11 segregation law of the Montgomery City code. The NAACP bailed her out of prison that evening.

“People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn’t true. I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.” – Rosa Parks, Rosa Parks: My Story, 1992

Rosa Parks was not the first to refuse to give up her seat, but her actions inspired the NAACP to organise a bus boycott. On 5th December 1955, the day of Rosa’s trial, campaigners distributed 35,000 leaflets saying, “We are … asking every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial … You can afford to stay out of school for one day. If you work, take a cab, or walk. But please, children and grown-ups, don’t ride the bus at all on Monday. Please stay off the buses Monday.” That day, over 40,000 black people walked to work instead of getting the bus. Some had to walk more than 20 miles through the driving rain.

As Rosa’s trial continued, so did the bus boycott. For 381 days, black people in Montgomery avoided using the bus. Since they made up at least 75% of commuters, the bus companies suffered from a loss in bus fares, forcing the city to repeal its law about segregation on public transport. Rosa did not wish to take credit for this success, and Martin Luther King Jr agreed that Rosa was not the cause of the boycott but the catalyst. “The cause lay deep in the record of similar injustices.”

Although Rosa became an icon of the Civil Rights Movement, she suffered as a result. She received many death threats, disagreed with King’s approaches, and both she and her husband lost their jobs, prompting them to move to Hampton in Virginia in search of work. Rosa found a position as a hostess but soon moved to live with her brother in Detroit, Michigan. Her brother believed the discrimination against blacks to be less severe in the northern states, but Rosa failed to see any improvements.

When African American John Conyers (1929-2019) stood for Congress, Rosa gave him her full support and convinced King to do the same. After Conyers’ election, he hired Rosa as his secretary and receptionist, a position she kept until she retired in 1988. She visited schools, hospitals and facilities with and on Conyers’ behalf, plus attended Civil Rights marches across the country. During this time, she became an ally of Malcolm X. She later took part in the black power movement.

Rosa continued to support the Civil Rights Movement in various ways, although she never took a leading position. During the 1970s, she helped organise the freedom of several prisoners whose actions of self-defence had landed them in police custody. Unfortunately, Rosa could not contribute much later that decade due to the poor health of her family, although she donated what little money she could to the cause. In 1977, both her husband and brother passed away from cancer. Following these losses, she broke two bones after slipping on an icy pavement, prompting her to move in with her elderly mother in an apartment for senior citizens. Her mother passed away in 1979, aged 92.

With renewed vigour, Rosa returned to the Civil Rights scene, co-founding the Rosa L. Parks Scholarship Foundation to provide scholarships for college students. When asked to speak at various organisations, Rosa usually donated her speaking fee to her scholarship foundation. Later, she established the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development, which aimed to “educate and motivate youth and adults, particularly African American persons, for self and community betterment.”

In her later years, Rosa faced several challenges. At 81, a man broke into her house and demanded money. When she refused, he attacked her, landing her in hospital with facial injuries. Rosa suffered severe anxiety after the attack and moved to a secure complex. Whilst she felt safe there, her fragile mind made it difficult for her to manage her finances. In 2002, she received an eviction notice due to a lack of rent payment. When members of the public found out, the Hartford Memorial Baptist Church in Detroit raised funds to pay the rent on her behalf, allowing her to remain in her home for the remainder of her life.

Rosa Parks passed away at age 92 on 24th October 2005. Before her funeral, a bus, similar to the one on which she refused to stand, drove her casket to the US Capitol in Washington DC, where she became the first non-government official to lie in honour in the rotunda. At her memorial service, the United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice (b.1954) said she believed that if it had not been for Rosa Parks, she would not be Secretary of State today.

At her death, Rosa left an extensive list of legacies, which continues to grow. Long before she passed away, places were named in her honour, such as Rosa Parks Boulevard in Detroit, and she received many medals and awards: Martin Luther King Jr. Award (1980), Presidential Medal of Freedom (1996), Congressional Gold Medal (1999), and several honorary doctorates. Since her death, the Rosa Parks Transit Center has opened in Detroit; Michigan renamed a plaza Rosa Parks Circle; the asteroid 284996 Rosaparks was named in her memory, and the Rosa Parks Railway Station opened in Paris. Americans also remember Rosa Parks with a statue in Montgomery, unveiled in 2019.

My blogs are now available to listen to as podcasts on the following platforms: Anchor, Breaker, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts and Spotify.

If you would like to support my blog, become a Patreon from £5p/m or “buy me a coffee” for £3. Thank You!

Pepe the Frog was a cartoon amphibian with a humanoid-like body created by Matt Furie (b1979) in 2005 for a comic called Boy’s Club. It quickly became an internet sensation with people sharing Pepe with various facial expressions as a way of displaying opinions about certain ideas. Variants include “sad frog”, “smug frog” and “feels frog”.

Pepe the Frog was a cartoon amphibian with a humanoid-like body created by Matt Furie (b1979) in 2005 for a comic called Boy’s Club. It quickly became an internet sensation with people sharing Pepe with various facial expressions as a way of displaying opinions about certain ideas. Variants include “sad frog”, “smug frog” and “feels frog”.

The Hope to Nope exhibition focused on a handful of demonstrations from the past decade, including video footage of marches and loud protests. A great deal of effort was focused on the Grenfell Tower tragedy, which occurred on 14th June 2017 and is still close to many Londoners’ hearts. A year on from the worst residential fire since the Second World War, hundreds of green-clad activists took part in a Justice for Grenfell Solidarity March demanding justice for the victims who lost their homes and loved ones. Investigations revealed that the incident was an accident waiting to happen and people are still angry about the way the situation was handled.

The Hope to Nope exhibition focused on a handful of demonstrations from the past decade, including video footage of marches and loud protests. A great deal of effort was focused on the Grenfell Tower tragedy, which occurred on 14th June 2017 and is still close to many Londoners’ hearts. A year on from the worst residential fire since the Second World War, hundreds of green-clad activists took part in a Justice for Grenfell Solidarity March demanding justice for the victims who lost their homes and loved ones. Investigations revealed that the incident was an accident waiting to happen and people are still angry about the way the situation was handled.

In Manchester, her home city, Emmeline Pankhurst is also being honoured with a statue. Scheduled to be completed in December 2018, sculptor Helen Reeves has designed the bronze tribute to “stand guard as an enduring reminder of the struggle for the vote, beckoning us to keep going forward as we continue the journey towards gender equality.”

In Manchester, her home city, Emmeline Pankhurst is also being honoured with a statue. Scheduled to be completed in December 2018, sculptor Helen Reeves has designed the bronze tribute to “stand guard as an enduring reminder of the struggle for the vote, beckoning us to keep going forward as we continue the journey towards gender equality.”

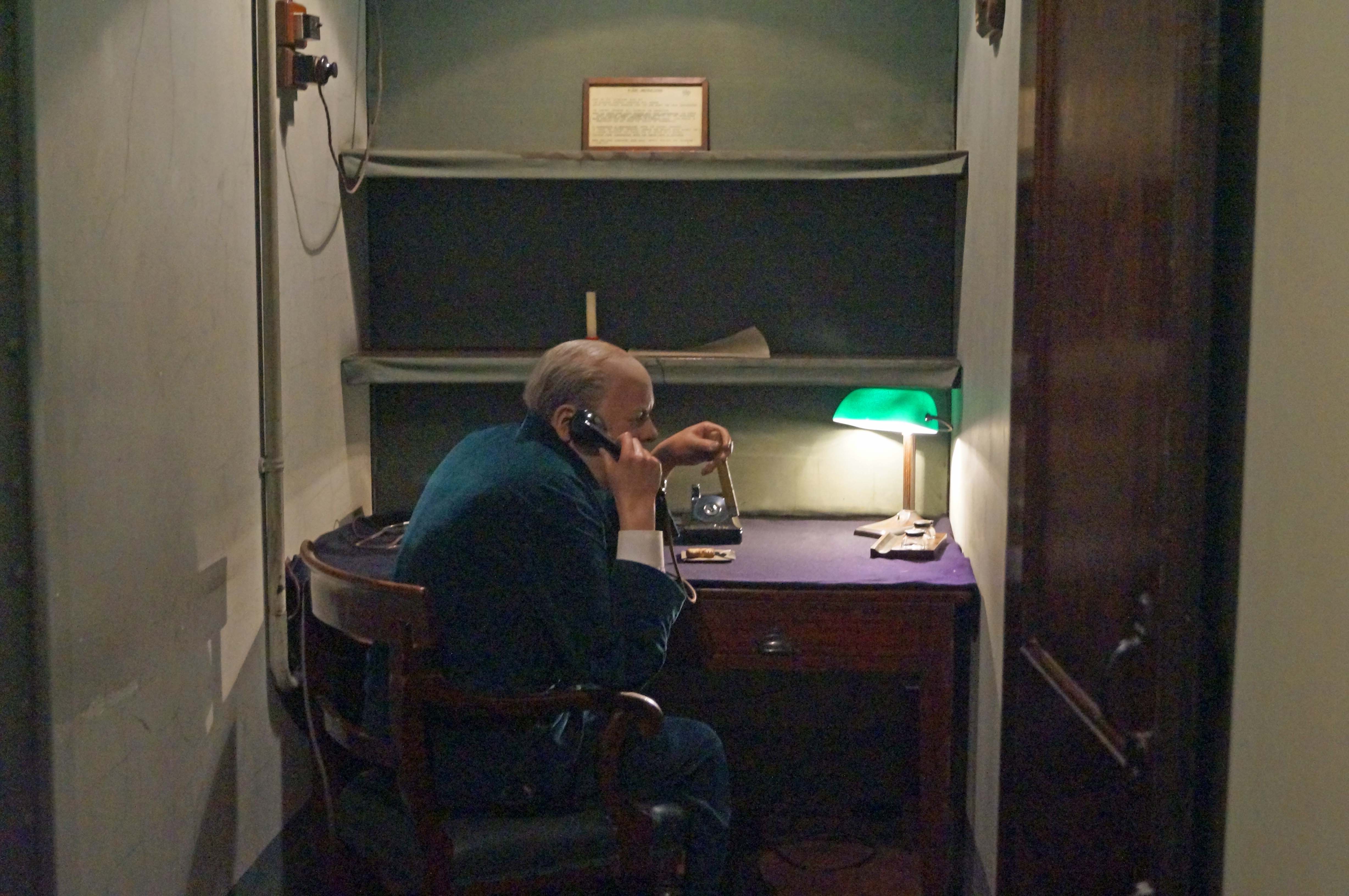

In the centre of the museum stands a 15-metre-long, digital, interactive table that provides a timeline of Churchill’s life. By using a touchstrip at the edge of the table, visitors can select and explore dates and events during Churchill’s life, viewing over 2000 documents, images and videos. This lifeline is continuously updated as more is discovered about the prodigious War Hero.

In the centre of the museum stands a 15-metre-long, digital, interactive table that provides a timeline of Churchill’s life. By using a touchstrip at the edge of the table, visitors can select and explore dates and events during Churchill’s life, viewing over 2000 documents, images and videos. This lifeline is continuously updated as more is discovered about the prodigious War Hero.