Renowned for his captivating portrait paintings, Tate Britain’s exhibition Sargent and Fashion explores the acclaimed works of John Singer Sargent, delving into his unique approach to portraying his subjects. Sargent used fashion to express identity and character and often chose his subjects’ attire or manipulated their clothing to achieve his desired artistic effect. The exhibition features nearly 60 of Sargent’s paintings, including rarely exhibited portraits. Additionally, period garments are displayed alongside the portraits in which they were worn.

Before John Singer Sargent’s birth on 12th January 1856, his father, FitzWilliam, worked as an eye surgeon at the Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. Following the loss of his older daughter, Fitzwilliam’s wife, Mary, experienced a breakdown, prompting the family to go abroad to recover. From then on, they lived as nomadic expatriates, primarily based in Paris but regularly moving to different European locations. Although they led a modest and quiet life, they avoided society and other Americans, except for friends in the art world. During their time abroad, six more children were born, but only four of them lived past childhood, including John Singer Sargent.

Although his father provided a basic education, Sargent preferred outdoor activities over his studies. Despite several unsuccessful attempts at formal schooling due to their nomadic lifestyle, Sargent became fluent in English, French, Italian, and German. His mother, an amateur artist, and his father, a medical illustrator, provided him with sketchbooks. His mother believed travelling throughout Europe and visiting museums and churches would provide Sargent with a well-rounded education. Sargent diligently worked on his drawings, often copying images and sketching landscapes. At thirteen, Sargent received watercolour lessons from Carl Welsch, a German landscape painter.

After an unsuccessful attempt to study at the Academy of Florence, Sargent began studying with the French portraitist Carolus-Duran (1837-1917) in Paris. In 1874, Sargent passed the exam required for admission to the École des Beaux-Arts, the premier art school in France, and took drawing classes, including anatomy and perspective. Sargent shared a studio with James Carroll Beckwith (1852-1917), who helped him connect with other American artists abroad.

Carolus-Duran taught Sargent the alla prima method, which, inspired by Diego Velázquez (1599-1660), involved working directly on the canvas with a loaded brush. This technique differed significantly from traditional ateliers, but Sargent soon impressed his peers with his exceptional talent, which allowed him to meet prominent figures in the art world, including Degas, Rodin, Monet, and Whistler. Despite his initial focus on landscapes, Sargent’s interest gradually shifted towards portraiture. Sargent’s first major portrait, depicting his friend Fanny Watts in 1877, marked his debut at the Paris Salon.

Following his time with Carolus-Duran, Sargent travelled to Spain, where he immersed himself in the works of Velázquez, absorbing the master’s technique and gathering inspiration for his own future pieces. Upon returning to Paris, Sargent quickly gained numerous portrait commissions, thus launching his career. In between commissions, he produced many non-commissioned portraits of friends and colleagues.

In the early 1880s, Sargent regularly exhibited portraits at the Salon, such as Madame Ramón Subercaseaux (1881). Amalia Subercaseaux and her husband Ramón, a diplomat, were some of the first clients of Sargent in Paris. Sargent portrayed Amalia as a fashionable woman, comfortable in her elegant home. Her white afternoon dress, featuring a long, buttoned bodice and pleated organza skirt, was adorned with black velvet, ribbon, and lace. Amalia’s pose, seated at the piano but turned towards the viewer, highlighted the train of her dress for maximum impact.

In Portrait of Madame X, Sargent depicts Virginie Gautreau (1859-1915) in a graceful pose that evokes classical sculpture. Although she was American, Gautreau lived in France and was celebrated in Parisian high society for her striking looks, which she accentuated with dramatic gowns and bold white makeup. Sargent persuaded her to sit for a portrait, promising to create “a tribute to her beauty.”

Although Portrait of Madame X is now one of Sargent’s most celebrated paintings, it is also his most controversial work. The first version of the portrait of Madame Gautreau featured an intentionally suggestive off-the-shoulder dress strap on her right side, creating a more daring and sensual overall effect. Sargent later repainted the strap to its over-the-shoulder position to reduce the controversy, but the damage had been done. It led to a decline in French commissions, and in 1885, Sargent considered giving up painting and going into music or business.

Observing the reactions of critics towards the original Portrait of Madame X, French poet Judith Gautier (1845-1917) wrote, “Is it a woman? a chimaera, the figure of a unicorn rearing as on a heraldic coat of arms or perhaps the work of some oriental decorative artist to whom the human form is forbidden and who, wishing to be reminded of woman, has drawn the delicious arabesque? No, it is none of these things, but rather the precise image of a modern woman scrupulously drawn by a painter who is a master of his art.”

Before the Madame X scandal, Sargent had considered moving to London and even sent paintings to the Royal Academy of Arts. One such painting, Dr Pozzi at Home (1881), depicts Samuel-Jean Pozzi (1846-1918), a Parisian doctor and gynaecology specialist associated with avant-garde art circles, who typically wore fashionable tailored suits. In a departure from the norm for portraits of professional men, Sargent portrayed him in an intimate domestic setting, dressed in a crimson dressing gown and Turkish slippers before a dark red curtain.

In England, Sargent spent more time painting outdoors than in the studio. His first success in the country was Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (1886), which helped to establish his reputation in Britain. Sargent spent over two years working on the painting, with most of the work done outdoors to capture the light as he desired. The inspiration for the painting came from Chinese lanterns hanging among trees and beds of lilies, which he saw while staying with friends in the Cotswolds. He then added the figures of two girls lighting the lanterns, both wearing specially made white dresses for the painting.

During his first trip to New York and Boston as a professional artist in the late 1880s, Sargent received over 20 important commissions, including portraits of Isabella Stewart Gardner, who became his patron. While in Boston, Sargent had his first solo exhibition, showcasing 22 paintings.

Upon returning to London, Sargent resumed his busy schedule. While some portraits were done in the client’s home, most were completed in his well-stocked studio, furnished with carefully chosen items for the desired effect. Unlike many artists, Sargent rarely used pencil or oil sketches, opting to apply oil paint directly. He also managed all tasks, including preparing canvases, varnishing the paintings, arranging for photography, shipping, and documentation.

In 1890, Sargent produced two non-commissioned portraits as show pieces for the Royal Academy, of which he became a full member in 1893. The first depicted Ellen Terry, a renowned British actress, as the Shakespeare character Lady Macbeth. Terry not only captivated audiences with her talent but also served as an inspiration to numerous artists and writers. When Sargent attended the premiere of Macbeth on 27th December 1888, he was so moved that he decided to create her portrait. Originally intending to depict a scene from the play, Sargent instead chose to portray Terry in a striking pose that highlighted her magnificent costume.

The second of these non-commissioned portraits was La Carmencita (1890). Carmen Dauset Moreno (1868-1910), also known as Carmencita, was a celebrated Spanish dancer who performed in the United States, Europe, and South America. Sargent was greatly impressed by her performances and had the opportunity to see her dance in New York on several occasions. He even painted her in a studio that he had borrowed, and she also danced at a private party in his studio in 1895. Carmencita was known for her dynamic and intricate movements, but Sargent portrayed her in a more static pose.

In the 1890s, Sargent averaged fourteen portrait commissions per year, including Mrs Hugh Hammersley and Lady Agnew of Lochnaw. Sargent formed a close friendship with Mary Hammersley (1863-1902), who often hosted him at her London residence, where he would mingle with fellow artists such as Walter Sickert (1860-1942). Sargent depicted her wearing a cherry silk velvet gown adorned with gold lace at the cuffs, hem, and neckline. Mary fondly recalled her experience of sitting for Sargent, noting that on some days, he would be entirely consumed by his work, while on others, he would charm everyone with his piano-playing skills. Portraits such as Hammersley’s inspired sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) to describe him as “the Van Dyck of our time”.

Lady Agnew (Gertrude Vernon, 1864-1932) welcomed Sargent into her London home to discuss her portrait and consider a variety of gowns. Eventually, they settled on a white silk gown with sheer organza sleeves and lavender trimmings. Sargent painted swiftly, completing the work in just six sittings, using long diagonal strokes to capture the purple sash and the light and shadow on the fabric of her lap. The portrait received great praise when exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1893, solidifying Sargent’s standing in Britain and leading to his election as a member of the Royal Academy soon after.

Sargent painted three portraits of novelist Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-94), including one with the author’s wife. Sargent became acquainted with Stevenson (1850–1894) in his early days in Paris. The joint portrait of husband and wife was completed in Stevenson’s residence in Bournemouth, England, during the peak of his literary success. In the painting, Sargent captures Stevenson’s restless energy, depicting him as “walking about and talking.” Stevenson is walking away from his wife, Fanny Stevenson (1840–1914), who is dressed in exotic attire and appears to be a peripheral and seemingly passive figure despite her strong personality. During the Victorian era, it was common for people to wear clothing from other cultures, often without consideration for the origins of the garments.

During his career as a portraitist, Sargent painted two Presidents of the United States of America, Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) and Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924). Sargent’s portrait of Wilson is less ostentatious than other portraits. The painting was created during the First World War when Sargent contributed a blank canvas to a fundraising effort for the British Red Cross. He agreed to paint a portrait if someone offered £10,000, and the successful bidder could nominate the sitter. Irish dealer and collector Sir Hugh Lane (1875-1915) offered to pay the amount but passed away before choosing a subject. He left his estate to the National Gallery of Ireland, which decided on President Wilson as the nominee.

In 1898, a wealthy Jewish art dealer named Asher Wertheimer (1843-1918), who lived in London, commissioned Sargent to create a series of twelve portraits of his family. It became the artist’s largest commission from a single patron. Sargent depicted Ena and Betty, the eldest Wertheimer daughters, in the family’s drawing room. Betty wore a striking red velvet evening gown and held an open fan, while Ena dressed in shimmering white satin. Sargent also painted a portrait of Ena dressed as a cavalier, holding a broomstick as a sword. In another painting, the younger sister, Almina, opted to wear a Turkish robe to emphasise the family were Ashkenazi Jews. British culture stereotypically exoticised Ashkenazi Jews by depicting them in typical Eastern clothing.

One of Sargent’s final notable sitters was Thomas Lister (1854-1925), an esteemed politician and huntsman who inherited the title of fourth Baron Ribblesdale from his father. Lord Ribblesdale embodied the spirit of the Edwardian aristocracy and was known for his meticulous attention to his appearance. After careful consideration, Sargent decided to portray Ribblesdale in his distinctive “ratcatcher” hunting attire, which he regularly wore, rather than a typical riding outfit.

In 1907, at fifty-one, Sargent decided to close his studio for good. He expressed relief, saying, “Painting a portrait would be quite amusing if one were not forced to talk while working… What a nuisance having to entertain the sitter and to look happy when one feels wretched.” Between 1906 and 1913, Sargent made several trips to the Swiss Alps with his sisters, Emily Sargent (1857-1936), a talented painter, and Violet Sargent (Mrs Ormond) (1870-1955), along with Violet’s daughters Rose-Marie and Reine. These family members became the subjects of several of Sargent’s paintings, such as Nonchaloir (Repose) (1911).

Sargent depicted Rose-Marie Ormond reclining, possibly asleep, on a sofa within an unidentified and opulent interior adorned with ornate French furniture. The focal point of the scene is the fabric. The sofa is draped with a dark patterned fabric, mirroring the design of the Kashmiri shawl enveloping Rose-Marie. The French title ‘Nonchaloir’ can be translated to mean indifference or a lack of concern.

Throughout his extensive career, Sargent created over 2,000 watercolour paintings while travelling across various locations such as the English countryside, Venice, the Tyrol, Corfu, the Middle East, Montana, Maine, and Florida. Through his watercolours, Sargent indulged in his early artistic passions for nature, architecture, exotic cultures, and mountain landscapes. Sargent also depicted his family, friends, gardens, and fountains in watercolour, often portraying them in Orientalist attire, set against brightly lit landscapes that allowed for a more vibrant colour palette than his commissioned works.

In 1907, Sargent journeyed to the Italian Alps, accompanied by an array of clothing likely obtained during his travels in West Asia. In The Chess Game (1907), Rose-Marie is depicted playing chess by a stream, dressed in a Turkish entari, pink slippers and pantaloons, and a draped cashmere shawl. Meanwhile, Sargent’s valet, Nicola d’Inverno, wearing Turkish şalvar (loose trousers) and a long jacket, is seated beside her. Similar to previous European artists, Sargent utilized traditional West Asian attire to craft a whimsical scene detached from the original context of these garments.

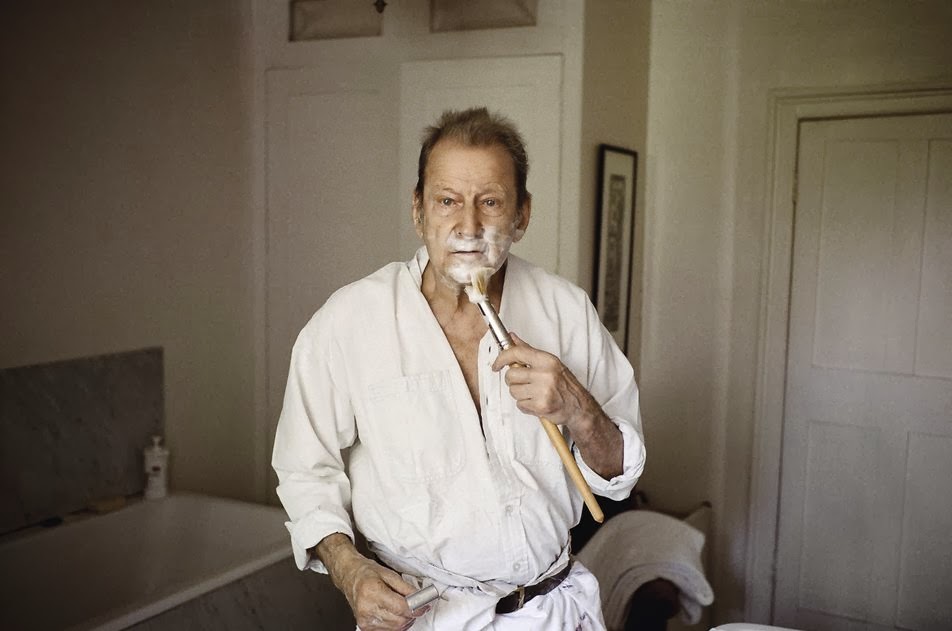

Sargent lived as a lifelong bachelor, maintaining a wide circle of friends, including Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), his neighbour of several years. While biographers once depicted him as reserved, recent scholarship suggests he was a private, complex, and passionate man with a possible homosexual identity. Sargent also had a reputation as “the painter of the Jews”, influenced by his empathy for their shared social otherness. Despite the homosexual rumours, Sargent had numerous relationships with women.

Sargent helped establish the Grand Central Art Galleries in New York City in 1922, where a significant retrospective exhibit of Sargent’s work took place in 1924. Following this, he returned to England and passed away at his Chelsea home on 14th April 1925 due to heart disease. Sargent was buried in Brookwood Cemetery near Woking, Surrey.

John Singer Sargent’s portraits not only depict Victorian and Edwardian fashion, but they also document the end of an era. Sargent stopped painting most commissioned portraits in 1907, turning his hand to large-scale mural projects and First World War scenes. By the 1920s, fashion changed due to the widespread availability of ready-to-wear clothing. No longer were women wearing the fitted garments in Sargent’s paintings.

Tate Britain celebrates Sargent as a skilled artist with an eye for fashion. His attention to detail records the colours, textures and weights of fabrics available in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He also demonstrated that clothing can reveal a great deal about a sitter.

Sargent and Fashion is open at Tate Britain until 7th July 2024. Tickets cost £22, although concessions are available. Advanced booking is recommended.

If you would like to support my blog, become a Patreon from £5p/m or “buy me a coffee” for £3. Thank You!