Russian Art 1917-1932

What do you think of when you hear the term ‘Russian Art’? The majority would probably picture geometric shapes, sharp angles and bright colours, but this is only an example of one genre of art that has emerged from Eastern Europe. It is one of the few styles that managed to spread to the Western world before the Russian government had an opportunity to crush it. Russian art is actually so protean, it cannot be summed up in a simple description. How would you describe British art, American art, French art, Italian art etc? So many movements have influenced artists, thus constantly changing the styles and fashions of each country. Russia was no different.

For centuries, Russia was under the autocratic rule of the Tsars until in 1917, provoking a civil war, Vladmir Lenin rose to power as a Communist leader. With this revolution came dramatic changes to Russian society, and art was swept up alongside it. Avant-garde artists were excited about the new developments and the opportunities they would bring about for creative individuals. However, their eagerness was short lived.

Lenin and the Bolshevik party came to power so suddenly, they has been unable to gain the support of the majority; therefore drastic measures needed to be taken to ensure they gained popularity. This, however, was not going to be an easy thing to tackle in the profusely illiterate country. For that reason, artists were given the task of spreading ideology through the means of mass propaganda.

In April 1918, Lenin revealed his Plan for Monumental Propaganda, which relied heavily on artists and photographers to carry out. Paintings, sculptures and everyday paraphernalia were utilised in order to glorify Lenin and the Bolshevik party. Graphic designers were commissioned to design posters sporting slogans that honoured the party. The colour red was often used to represent the revolution.

One of the most shocking tasks Lenin demanded was the removal of artworks used by the Russian Orthodox Church, replacing the figure of Jesus with an icon of himself. It is hard to imagine how a predominantly Christian country would agree to let this happen, however, it did, and Lenin became almost saint-like.

After Lenin’s death, Russia became a very dangerous place to live, especially for artists who wanted to express their own voices. Joseph Stalin took Lenin’s place as leader of the Soviet Union. Throughout his dictatorship, Stalin made many changes and demands. One of these was the proclamation that Socialist Realism was the only acceptable artistic style. Gone were the opportunities for artists to experiment with their creativity. Ironically, the artworks accepted hardly revealed the truth about the Soviet Union, despite being classified as Realism.

Stalin believed that Russia was behind the times and was determined to industrialise the country. He introduced the concept of a Five-year Plan, which would set targets for every factory and farm belonging to the Soviet Union. Physical labour was demanded of all citizens in order to reach these goals. To encourage the population, Stalin commissioned – or more likely forced – designers, photographers, film producers etc. to promote his scheme. Photography was perhaps the preferred medium since its content is more believable than a painting and could be easily reproduced on posters and spread amongst the masses. However, these photographs were often staged in order to make situations appear better than they really were. Behind the lies of smiling faces, most workers were treated like slaves, often imprisoned or killed for not working as well as others. Thousands died from accidents, starvation or poor living and working conditions during this period.

Kazimir Malevich

The effects of the Russian revolution and Stalin’s dictatorship is evident through many artists’ changing styles. Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935) is a significant example of this. Although Social Realism was not enforced until the very end of his life, the reshaping of Malevich’s personal style documents the gradual elimination of techniques by the Soviet Union.

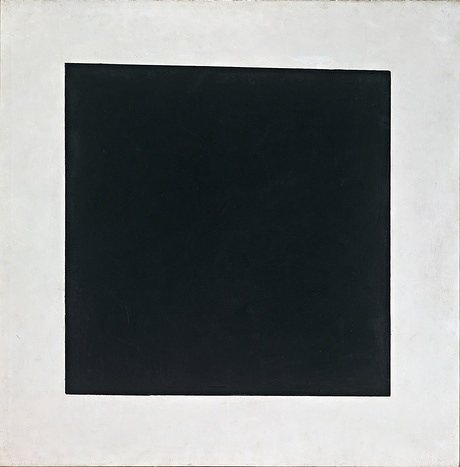

Black Square 1929 by Kazimir Malevich. Photograph: State Tretyakov, Moscow, Russia

Born pre-revolution, Malevich believed that art was a method of expressing spirituality, therefore outcomes need not be realistic, and could be based on metaphor rather than truth. At the height of his career in 1915, Malevich patented a style named Suprematism, a purely abstract art movement characterised by the use of geometric shapes and a limited range of colour. A particular famous piece that symbolises this movement is Black Square.

Unfortunately, Malevich’s movement was eventually denounced by Soviet authorities on the basis that it failed to convey social realities.

Malevich attempted to conform to Soviet ideology, however was still adamant to work in an abstract style. Despite rebelling against the governments artistic rules and regulations, Malevich’s new paintings were accepted and displayed at the State Russian Museum in 1932.

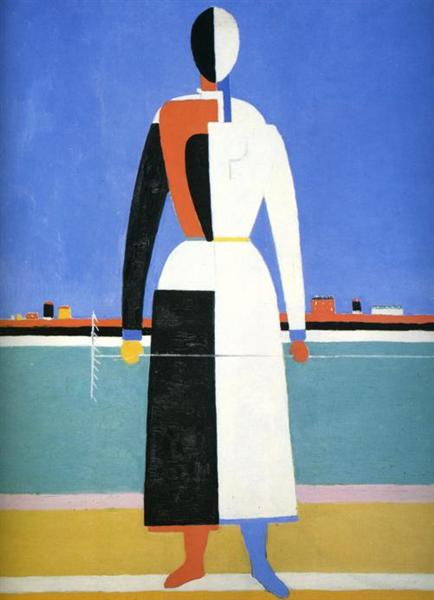

Woman with Rake, c.1932 Photo:as above

Presumably the subject matter of Malevich’s paintings were what granted him approval to painting in an abstract style. Depicted were anonymous figures showing peasant workers out in their fields. The blank faces and limited colour make up a characterless person that hides the truth about their working conditions. On the other hand, it also represents the loss of identity these people felt under the oppressive rule of Joseph Stalin.

At the very end of his life, shortly before dying of cancer, Malevich was painting in a style that the Soviet Union was enforcing throughout the country. Contrasting Malevich’s final self-portrait with an earlier one shows these dramatic changes and emphasises the control the Soviets’ held.

Although there were artists who refused to conform, yearning for the days when art showed the beauty and charm of Tsarist Russia, the world saw a utopian version, hiding the terrible truths.

As you can see, it is impossible to categorise something as “Russian Art”. There is pre-revolution art, which encompasses a wide variety of styles, and then there is Soviet Art, a “realistic” portrayal of Russia under Lenin, and then Stalin – as long as it expressed Communist ideology. Then, of course, there are contemporary artists living in a post-Soviet country, giving “Russian Art” a brand new meaning.

To fully understand the effects the Soviet Union had on the art world, it is best to see it with your own eyes. Luckily we have hindsight on our side, preventing us from falling into the trap of believing the lies and exaggerations shown in paintings and photographs.

Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1931 is an exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, London. You have until 17th April 2017 to go and see it.