Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites

Organised by the National Gallery in collaboration with Tate Britain, the Arnolfini Portrait painted by Jan van Eyck (c1390-1441) takes pride of place in an exhibition about the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Although this portrait was painted 400 years before the founding of the group, it had a significant impact on a group of British artists who wanted to break away from the stagnant style of painting of the 1800s. Reflections: Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites explores the connection between one famous oil painting and the many artists it inspired.

The Arnolfini Portrait was obtained by the National Gallery in 1842, the 186th piece of work added to the growing collection. What made it extra special was the nationality of the artist. Jan van Eyck lived in the Netherlands and this portrait was the first painting the gallery received from this country. Available to public view for the first time, many flocked to see and study the painting, including William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-82) and John Everett Millais (1829-96), the founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Jan van Eyck is the most acclaimed painter of the Early Netherlandish School and one of the first to use oil paints – he was originally believed to be the inventor of oil painting, but this has since been disproved. Little is known about his early life, however, from 1432-9, van Eyck helpfully dated all his paintings, allowing art historians to determine his whereabouts and the people with whom he associated. Two other van Eyck paintings are in this exhibition, however, it is the Arnolfini Portrait, sometimes called Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife (1434), that remains his most famous.

Van Eyck – Arnolfini Portrait

In this exhibition, the portrait is referred to as the Arnolfini Portrait and reveals a man and woman holding hands in a bedroom. This couple has been identified as members of the Italian Arnolfini family, the man possibly being Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini who lived in Bruge at a similar time to van Eyck. From the date of the painting, 1434, it has been determined that the woman was Arnolfini’s second wife.

The figures are dressed in the fashions of the time, which today look rather peculiar. Arnolfini’s dark purple coat or jerkin appears to be made of velvet, but it is his black hat that makes him look rather odd. His wife, on the other hand, is much more brightly clothed in a fur-lined green gown.

Although the foreground characters have now been identified, the purpose of the portrait was lost for many years. This resulted in a large number of theories about the intended subject of the painting. Some believed that it showed a husband and wife, and others believed that it was a promise of future marriage. The theories escalated with the notion that the woman was pregnant, therefore a hasty marriage is occurring in private, however, the old-fashioned costume may be the cause of the appearance of a swollen stomach.

The National Gallery does not pay too much mind to the purpose of the painting, preferring to draw visitors’ attention to the items in the background. Although the room appears to be rather small with plain walls and uncarpeted flooring, other objects suggest the couple is richer than they may initially appear. On the window sill sit a few oranges, which were an expensive fruit during the 1400s, and above the couple hangs an intricate, polished chandelier.

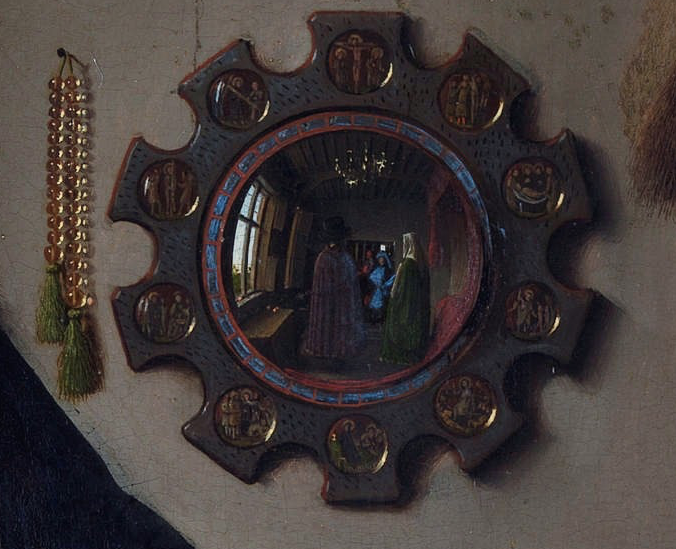

The key element of the Arnolfini Portrait, however, is the convex mirror hanging on the wall behind the couple. Mirrors were considered a luxury at the time of painting, therefore, also hint at the wealth of the Arnolfini family. Within its reflective surface, two male figures can be seen entering the room, giving the painting more depth and sparking more theory about its purpose – some suggested that the figures in the mirror could be witnesses of the marriage.

The mirror in the Arnolfini Portrait

The mirror itself is quite fascinating; van Eyck has successfully painted the glass to look like a real mirror, but the detail in the frame is even more impressive. Around the edge are ten small circles showing the scenes from the Passion of Christ. Although they are tiny, each scene has been carefully painted fully.

According to a ten-minute film included in the exhibition ticket price, the Arnolfini Portrait was not appreciated by people at the time of completion. It was not a popular piece of work and often changed hands, being passed from one owner to the next. However, this all changed in the 19th century. The realistic nature of the outcome was highly admired, as well as the pristine condition it was in despite its age. At this time, paintings would often degrade quickly, therefore, many were intrigued by the artist’s technique.

“A picture has just been added to the National Gallery which affords as much amusement to the public as it administers instruction to the colour-grinders, painters, and connoisseurs, who, since the day of its exhibition, have crowded rooms to admire its singularity and discuss its merits. To every one it is a mystery. Its subject is unknown, its composition and preservation of its colours a lost art.”

– Illustrated London News, 1843 (a copy features in this exhibition)

Jan van Eyck used paintbrushes to apply the oil paint to the canvas, however, he also used his finger to help blend the colours together. This may also have helped to produce the smooth finish since no individual brush stroke can be detected.

It was after the Arnolfini Portrait was put on display that three young students from the Royal Acadamy began their revolutionary art movement. Hunt, Rosetti and Millais were disappointed with the High Renaissance method of teaching they were receiving at the academy, therefore, were fascinated with the painting by van Eyck. They decided to revive the techniques used in the early artwork in Italy and the Netherlands of the fifteenth century, produced before the emergence of Raphael and his style of painting. As a result, they named their movement “The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood”.

Although the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood only had three founding members in 1848, they quickly added other artists to the group who shared their dissatisfaction with the Royal Academy. They developed rules, which whilst never published, were closely followed by all members of the brotherhood.

- To have genuine ideas to express.

- To study nature attentively, so as to know how to express it.

- To sympathise with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parading and learned by rote.

- To produce thoroughly good pictures and statues.

The Pre-Raphaelites aimed to produce genuine ideas that evoked emotion. They moved away from the popular military victory and classical history paintings in favour of what they thought were more serious subjects. Some of their outcomes had a religious nature, however, they also took inspiration from literature, for example, Shakespeare and Tennyson.

“… absolute, uncompromising truth in all it does, obtained by working everything down to the most minute detail, from nature, and from nature only.” – John Ruskin (1819-1900)

Mariana by Sir John Everett Millais (1851)

The Pre-Raphaelites were not only influenced by van Eyck’s style of painting, they were particularly intrigued by the use of the mirror in the background. The National Gallery has focused on this motif rather than the movement in general, with a selection of Pre-Raphaelite artworks that feature mirrors.

One painting that the National Gallery has deemed important enough to use on advertisements for the exhibition is Marianna (1851) by Sir John Everett Millais.

Millais was a thriving portraitist whose paintings of beautiful young women earned him popularity. He had a taste for Shakespeare plays and Tennyson’s poems and often painted scenes based upon them. Mariana was a character in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure but also features in a poem by Tennyson. In this particular scene, Mariana has been sent into exile by her fiancé Angelo after her dowry was lost at sea.

The mirror in this composition does not play much of a role, however, an accompanying drawing in the exhibition suggests that Millais originally intended to include a mirror behind Mariana’s head. However, art critics still link Mariana with the Arnolfini Portrait. They claim that Mariana’s rich blue dress emphasises the curvature of her spine and slim figure in a similar way that the bright green gown in the van Eyck painting amplifies the swelling stomach of the Arnolfini woman.

The National Gallery explores the different ways that mirrors are used in the artworks by Pre-Raphaelite painters. Some painters used mirrors in a metaphorical sense, often to suggest ideas or feelings that could not be conveyed through the main section of the painting. One example of this is William Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience (1853).

The Awakening Conscience (1853) by William Holman Hunt

Hunt’s painting shows a wealthy man with his mistress who appears to be in a slight state of undress. She is captured in a position suggesting she is just raising herself up from the lap of her lover. Her facial expression clearly illustrates that something has captured her attention beyond the painting’s frame. This is where the mirror plays a vital part.

Beyond the two figures, Hunt has positioned a large mirror which reflects what those studying the painting cannot see. The mirror is facing a window that looks out into a brightly lit garden. No one can know for certain what the lady has seen, however, the picture notes at the National Gallery suggest that she may have been reminded of her lost innocence. She is rising up as if her conscience has been awakened and it is not too late to escape her morally corrupt situation. “… the sunlit garden reflected behind her suggests that she will choose a path towards spiritual enlightenment, and that faith will be her salvation.”

As time went on, members of the Pre-Raphaelite movement began to move away from their initial aims, blurring the lines between their radical ideas and the commencement of the Aesthetic Movement. Not all Pre-Raphaelites were sucked into this new concept, however, those that were, took their mirror motif with them. With a new aim of creating art for art’s sake, the mirrors were used to emphasise beauty and reality rather than having any stronger symbolic nature.

Il Dolce far Niente (1859-66) by William Holman Hunt

From the selection of paintings that the National Gallery grouped into this category, the one that stands out the most is Il Dolce far Niente (1859-66) which was also painted by William Holman Hunt. Hunt was one of the Pre-Raphaelite painters who prefered to convey an enlightening purpose or narrative, which makes this particular painting an anomaly.

Il Dolce far Niente, which translates into English as “it is sweet to do nothing”, is a portrait that focuses on female beauty. The convex mirror in the background, tying it in with the majority of the other paintings in the exhibition, shows a reflection of the snug domestic scene, however, adds little else to the composition.

Apparently, the original painting was intended to be a portrait of Hunt’s fiancé, Annie Miller, but the engagement was eventually broken off. Hunt later repainted the face to turn it into a portrait of his wife, Fanny Waugh, whom he married in 1865.

When the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood combined their fascination of the convex mirror with their love of literature, the perfect poem was found. The Lady of Shalott (1832) by Sir Alfred Tennyson (1802-92) provided painters with potential scenes to show off their artistic style inspired by the Arnolfini Portrait. This ballad tells the story of a woman under a curse who cannot engage with the outside world. The only safe way to view the goings on outside her prison is through a mirror that faces a window. She spends her time painstakingly reproducing these reflections on a loom until one day she catches sight of the striking Sir Lancelot. Forgetting herself, she watches him from the window; the mirror cracks and her death is inevitable.

The poem, written in four parts and nineteen stanzas, supplied the Pre-Raphaelites with many scenes to illustrate, making good use of the prominent mirror. Four examples are shown in the exhibition, revealing different interpretations. Three of the four chose to encapsulate the curse in action, emphasising the cracking mirror and the Lady of Shalott facing the window, distraught with the realisation about what she has done.

The Lady of Shalott (1894) by John William Waterhouse

John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), was born at the same time the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was established. Although the movement had largely come to the end by the time he started his career, he was still influenced by their style. Waterhouse was also guided by other artists’ techniques of his era, for example, Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1865-1940), therefore his outcomes are not as smooth and detailed as the founders’ artwork.

Nevertheless, Waterhouse was one of the painters who attempted to demonstrate the curse of the Lady Shalott. The background contains the typical circular mirror complete with the crack symbolising the protagonist’s demise. The lady herself is tangled up in the skeins of wool, emphasising that she cannot escape her dreadful fate.

“I am Half-Sick of Shadows, Said the Lady of Shalott” (1913) by Sidney Meteyard

The painting that does not depict the breaking of the mirror is, perhaps, the most striking of the selection, if not the most beautiful in the whole exhibition. Sidney Meteyard (1868-1947), who was too late for the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood but worked in a later revival of the style, used rich, dreamlike colours to illustrate the fairytale-like ballad. Taking the title directly from a line in the poem, “I am Half-Sick of Shadows, Said the Lady of Shalott” (1913) reveals the lady dozing in front of the mirror and loom after witnessing two lovers who can still be seen in the convex mirror.

“But in her web she still delights/To weave the mirror’s magic sights,/For often thro’ the silent nights/A funeral, with plumes and lights,/And music, when to Camelot;/ Or when the moon was overhead, Came two young lovers lately wed;/’I am half sick of shadows,’ said/The Lady of Shalott.”

– The Lady of Shalott, Tennyson, Part II, final verse

The expressive colours emphasise the dream-like state the Lady of Shalott. It suggests she may be dreaming of the lovers or imagining herself in a similar scenario, which she will never get to experience in real life. The flowers in the foreground, which help to frame the painting, also indicate the romantic, intimate scene the lady has recently witnessed.

From this exhibition, the National Gallery stresses the influence the Arnolfini Portrait with its convex mirror had on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. However, these were not the first people to be affected in this way. Long before Hunt, Rosetti and Millais began to make a fuss about the Royal Academy’s teaching methods, the painting was spotted by a seventeenth-century artist in the Spanish Royal Collection. Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) was enamoured with van Eyck’s portrait and went on to produce the second most famous mirror in the history of Western art.

Partial copy of “Las Meninas” (1862) by John Philip

The original painting, Las Meninas (c1656) is very famous and recognisable, however, it is currently hanging in the Museo Nacional Del Prado in Madrid. Fortunately, the National Gallery was able to display a partial copy of Las Meninas produced by John Philip (1817-67) in 1862. This copy shows approximately one-quarter of the original composition showing the detail in the bottom left-hand corner.

The partial copy by the Scottish artist brings in to focus the mirror hanging on the wall amongst a selection of framed paintings. This feature is likely to be overlooked in the original, the lighting drawing attention to the girls in the foreground.

Whilst the mirror is not round, as it is in the Arnolfini Portrait, it adds a further dimension to the painting. In the dark glass, the figures of the King and Queen of Spain can be seen, who do not feature anywhere else in the composition. This has resulted in the meaning of the painting remaining ambiguous, with critics coming up with varied suggestions about the purpose of the King and Queen’s presence.

The Pre-Raphaelites were not impressed with Las Meninas in the same way that the Arnolfini Portrait struck them. Although it contained a mirror, the painting style leant more towards impressionism than van Eyck’s hard-edged style. It was the photorealistic aspect that the Brotherhood wanted to replicate more than anything else.

Reflections: Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites is a visual journey of the Pre-Raphaelite movement and the effect a single painting can have on a large number of people. By limiting the display to paintings featuring mirrors, the National Gallery compares and contrasts the various interpretations artists developed. It is interesting to see how one key idea – a mirror – can result in so many different outcomes.

Occasionally, the National Gallery’s claim that various paintings were inspired by the Arnolfini Portrait is debatable, but, assuming this conclusion was reached by experts, visitors can only take their word for it. Regardless of whether the connection is obvious or not, the selection of paintings is beautiful and intriguing, and worth taking the time to study.

The National Gallery provides an audioguide at a small extra cost and has detailed notes throughout the exhibition explaining the paintings and the thoughts of the Pre-Raphaelites. By introducing the public to poems, such as The Lady of Shallot, the exhibition is as educational as it is entertaining.

Reflections: Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites remains on display in the Sunley Room at the National Gallery until 2nd April 2018. Tickets are £10 on weekdays and £12 at weekends.

What a major piece of writing. So interesting and educational, thank Hazel for spending the time to Marshall your ideas and present them so clearly

and compelling me to keep on reading.

You are a star.

I look forward to next week’s blog.

Pingback: The Great Spectacle | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Exploring London the Fun Way | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: The Life and Designs of William Morris | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Edward Burne-Jones | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: A Walk Through British Art | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: A Lone Woolf | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: The Power of Seeing | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Van Gogh and Britain | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Pre-Raphaelite Sisters | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: The Self-Portraits of Lucian Freud | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Spot the Cat | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: The Tale of Beatrix Potter | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Childhood: A Visual Story | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Simeon Returns to Bristol: Part Two | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Bible By Colour | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Bible By Colour – Part 2 | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Whistler’s Woman in White | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Poet and Painter | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Tate Britain’s New Acquisitions | Hazel Stainer