After captivating audiences in Beijing, Barcelona and Seoul, the official Meet Vincent van Gogh Experience has arrived in London. When Vincent van Gogh died in 1890, not only did he leave behind a great number of paintings and drawings, his voice was captured in hundreds of letters to his brother and other friends and acquaintances. Using the wealth of information in these correspondences, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam has designed an exhibition through which the artist speaks directly to the visitor. An audio guide tells Van Gogh’s story, reading directly from many of his letters in order to teach visitors everything they need to know about one of the most celebrated artists in the world.

Please do touch! Nothing is off-limits in this experience, there are no ropes separating visitors from exhibits. Large recreations and 3D prints of Van Gogh’s works allow people to see and feel the texture of the paint. Reproductions of tools and materials help to demonstrate the artist’s method and technique, and interactive stations throughout the experience encourage visitors to create their own art, using the words of Van Gogh as their guide.

Unlike art galleries where everything is neatly hung on walls, the Van Gogh Experience uses digital projections, props, and videos to make it feel as though one is walking directly into a Van Gogh painting. The breaking down of traditional boundaries lets visitors pull up a chair at the Potato Eater’s table, sit on a haystack, stand beside the Yellow House and enter Van Gogh’s recognisable bedroom.

As you progress through the exhibition, the scenes change, revealing key turning points in Vincent’s life. With his disembodied voice in their ears, visitors accompany the artist from Nuenen in the Netherlands to Paris, Arles, Saint-Rémy and Auvers-sur-Oise in France. Engaging with the sets provides the opportunity to feel as though you are seeing the world and his paintings through Van Gogh’s eyes.

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born on 30th March 1853 in Zundert, Netherlands. He was the first surviving child of the Dutch Reformed Church minister Theodorus van Gogh (1822-85) and Anna Cornelia van Gogh-Carbentus (1819-1907), born exactly a year after a still-born brother. Vincent had many siblings: Anna (1855-1930), Theo (1857-91), Lies (1859-1936), Willemien (1862-1941) and Cor (1867-1900); however, it was with Theo that Vincent had the strongest relationship.

At least 902 letters of Van Gogh still exist, 819 of which he sent and 83 he received. Vincent burnt the majority of correspondence he received since it was impossible to keep them all; Theo, on the other hand, did not like to throw things away and managed to save 658 letters from his brother. Twenty-one letters to his sister Wil (Willemien) also exist, however, there appear to be none addressed to his other siblings.

Vincent was initially taught at home by his mother and a governess before joining the village school in 1860. In 1864, however, he was sent away to boarding school where he felt abandoned and deeply unhappy. Eventually, he returned home and his uncle obtained him a position at the art dealers Goupil & Cie in The Hague. After completing his training in 1873, Vincent was sent to Goupil’s London branch where he began earning more money than his father. In retrospect, it is believed this was the best year of Van Gogh’s life.

The earliest dated letter from Vincent to Theo was sent in September 1872 in which he begins to confide in his brother, telling him about the things he has seen or read. “You must write to me in particular about what kind of paintings you see and what you find beautiful.” (January 1873) The letters continued during Vincent’s time in London where he regularly visited museums. “English art didn’t appeal to me much at first, one has to get used to it.” (January 1874)

Theo began working with Goupil & Cie three years after his brother, which made their relationship even stronger. Vincent’s letters, however, had become rather gloomy, often writing about a “quiet melancholy”. This may have been triggered by the rejection of Eugénie Loyer who he had confessed his love to whilst living in London. Vincent began to isolate himself and became religiously fervent, adopting the words “sorrowful, yet always rejoicing” (2 Corinthians 6:10) as his motto.

Van Gogh’s father and uncle arranged for him to be transferred to Goupil’s Paris branch, however, due to Vincent’s poor attitude, he was dismissed in 1876. Over the next few years, Vincent explored a variety of career possibilities, including returning to England to work as an unpaid supply teacher in Ramsgate. This proved unsuccessful, so he returned home where he worked at a bookshop in Dordrecht. This also proved futile and Vincent spent hours doodling or reading the Bible.

Even though Van Gogh’s father was a minister, he thought his son’s religious passion was excessive. Nonetheless, to support Vincent’s new-found desire to become a pastor, his father sent him to live with his uncle and theologian Johannes Stricker (1816-86). Unfortunately, Vincent failed the entrance exam for the University of Amsterdam, nor did he pass the three-month course at a Protestant missionary school in Laken, Belgium.

Undeterred, in 1879 Vincent took up a missionary post in the coal-mining district of Borinage in Belgium. Up until this point, his letters to Theo had contained passages or references to the Bible, however, his experience of the squalid living conditions made him turn his back on religion. Feeling that he had no career prospects and nowhere to go, Vincent returned home.

After a few months living with his parents and a brief spell in a lunatic asylum – presumably for depression, Vincent returned to Borinage where he temporarily lodged with a miner. A letter written to Theo at the time suggests Vincent had stopped writing to him during his difficult period. “My dear Theo, It’s with some reluctance that I write to you, not having done so for so long … Up to a certain point you’ve become a stranger to me, and I too am one to you, perhaps more than you think…” (August 1880)

Whilst living in Borinage, Van Gogh became interested in the people and scenes around him, producing quick sketches, which he sent to Theo. His letters became both a means of communicating and a way of documenting his ideas. Encouraged by his brother’s new way of expressing himself, Theo encouraged Vincent to take up art in earnest. Van Gogh followed Theo’s recommendation, eventually registering at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts. Vincent’s early sketches in Borinage proved to be more than a desire to draw but also the inspiration for Van Gogh’s first major work, The Potato Eaters.

The Potato Eaters (De Aardappeleters)

Five Persons at a Meal

By the end of 1883, loneliness or, perhaps, poverty had driven Van Gogh to move in with his parents, who were then living in the Dutch town of Nuenen. During his two year stay, Vincent completed many drawings, watercolours and oil paintings of the local weavers and cottages. Unlike the vivid colours of his later work, Vincent worked in sombre earth tones to capture the true nature of the scenes.

The colours inadvertently reflect the events in Van Gogh’s life during the period he stayed with his parents. In August 1884, the neighbour’s daughter Margot Begemann fell in love with Vincent and he, reluctantly at first, developed a strong relationship with her. They both wished to marry but their families were strongly against the proposal. Upset, Margot swallowed rat poison and was rushed to hospital where she was lucky to survive. Unfortunately, Vincent received another blow not long after this incident on 26th March 1885 when his father died.

Nonetheless, Van Gogh continued with his drawings and paintings then, the same year, Theo wrote to him asking if any of his paintings were ready to exhibit. Vincent replied that he had been working on a “series of peasant studies” and submitted his first major work, The Potato Eaters. This was a culmination of several years work, taking inspiration from the people in Nuenen, who often sat for him, as well as his experience in Borinage.

“You see, I really have wanted to make it so that people get the idea that these folk, who are eating their potatoes by the light of their little lamp, have tilled the earth themselves with these hands they are putting in the dish, and so it speaks of manual labour and—that they have thus honestly earned their food. I wanted it to give the idea of a wholly different way of life from ours—civilized people.”

– Vincent to Theo (30th April 1885)

Two years later, Van Gogh considered The Potato Eaters to be “the best thing I did”, which he confessed in a letter to his sister Wil. Critics, on the other hand, were less inclined to agree, including Vincent’s friend and fellow artist Anthon van Rappard (1858-92). Initially, Vincent was angry with Rappard’s criticism and told him that he “had no right to condemn my work in the way you did” (July 1885). A month later, with his confidence in tatters, Vincent tried to defend his efforts, writing “I am always doing what I can’t do yet in order to learn how to do it.”

In November 1885, Van Gogh spent a brief time living in a room above a paint dealer’s shop in Antwerp. Although Theo supported him financially, Vincent chose to spend the money on painting materials rather than food. He also bought Japanese ukiyo-e woodcuts, which he studied and copied, incorporating some elements into his paintings. He also broadened his palette, beginning to paint in reds, blues and greens.

“My studio’s quite tolerable, mainly because I’ve pinned a set of Japanese prints on the walls that I find very diverting. You know, those little female figures in gardens or on the shore, horsemen, flowers, gnarled thorn branches.”

– Vincent to Theo (28th November 1885)

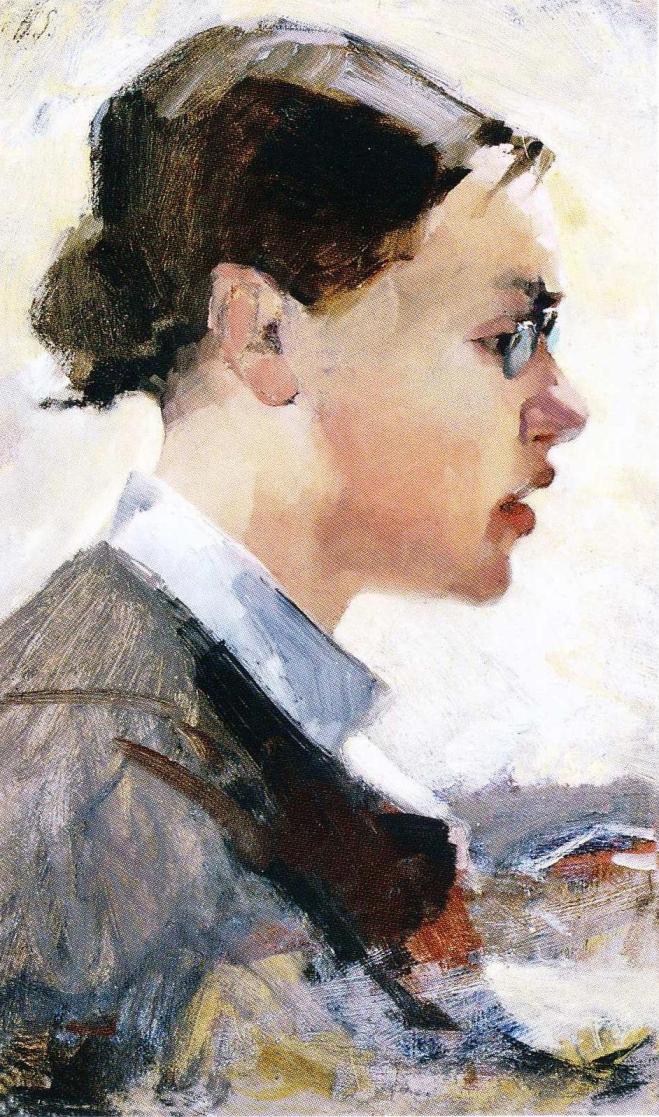

Portrait of Vincent van Gogh – Toulouse-Lautrec

Due to living in poverty and eating poorly, Van Gogh was hospitalised between February and March 1886, after which he moved to Paris where he lived with Theo. Since they were living together, there was no point in writing to each other, therefore, not a lot is known about Vincent’s time in Paris.

Other sources of information reveal Vincent spent time in the Louvre, examining paintings, colour schemes and artists’ techniques. Through Theo, he met up-and-coming artists, such as Émile Bernard (1868-1941) and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901).

Theo found living with Vincent almost unbearable and, although they remained firm friends and brothers, Vincent moved in 1887 to Asnières in the northwest of Paris. Here, Vincent met Paul Signac (1863-1935), a neo-impressionist painter who helped develope the Pointillist style. Inspired by Signac, Vincent began to include aspects of pointillism in his paintings.

-

-

The Yellow House, 1888

-

-

Starry Night over the Rhône, 1888

-

-

Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers, 1888

Van Gogh’s artistic breakthrough occurred after he had moved to Arles in the south of France in an attempt to recuperate from his smoking problem and smoker’s cough. It is believed he had the intention of founding an art colony, however, this never came to fruition. Nonetheless, existing letters reveal Vincent was in contact with several artists at the time, including Bernard, Charles Laval (1862-94) and Paul Gauguin (1848-1903).

During his year in Arles, Van Gogh produced over 200 paintings and 100 drawings, the majority of which were intended for the decoration of the Yellow House – a personal gallery of his work. When Vincent first arrived in Arles, he signed a lease for the eastern wing of the Yellow House at 2 Place Lamartine, however, it was not yet fully furnished so he was only able to use it as a studio. Meanwhile, he resided at the Hôtel Carrel and the Café de la Gare.

The Night Café, 1888

“I want to do figures, figures and figures … Meanwhile, I mostly do other things.” Van Gogh desired to paint portraits and, whilst he painted a few, he mostly produced landscapes. Inspired by the local harvests, wheatfields and landmarks, Vincent painted Arles in yellow, ultramarine and mauve. The wheat fields were a common feature in his landscapes, however, Vincent also painted his house, sunflowers, fishing boats and the Café de la Gare. Writing about one of his paintings of the latter entitled The Night Café, Van Gogh revealed he was trying to “to express the idea that the café is a place where one can ruin oneself, go mad, or commit a crime”.

Bedroom in Arles, 1888

Once the Yellow House was suitable to live in, Van Gogh began displaying some of his paintings on the walls as can be seen in his depiction of his bedroom: Bedroom in Arles. When planning this painting, Vincent wrote to his brother that “colour must be abundant in this part, its simplification adding a rank of grandee to the style applied to the objects, getting to suggest a certain rest or dream.” The walls are a pale violet and the wooden furniture is “yellow like fresh butter”. On the bed, a scarlet bedspread lies on top of a “lemon light green” sheet and pillows. The windows are shuttered and the blue doors closed, one which led to a staircase and the other a guest bedroom.

-

-

Van Gogh’s Chair, 1888

-

-

Paul Gauguin’s Armchair, 1888

The guest room was used by Paul Gauguin when he agreed to visit Van Gogh in Arles. While waiting for him to arrive, Vincent frantically worked on paintings to decorate the house, including more sunflowers, a painting of his chair and a painting of the chair he had purchased in anticipation of Gauguin’s visit.

The Painter of Sunflowers by Paul Gauguin, 1888

Gauguin eventually arrived on 23rd October and the artists settled into a routine of sleeping and painting in the Yellow House. Noticing that Van Gogh always used visual references, Gauguin encouraged Vincent to paint from memory. They also went on outdoor ventures to paint en plein air, however, the only painting Gauguin completed in Van Gogh’s studio was The Painter of Sunflowers, a portrait of Van Gogh.

Van Gogh had hoped for friendship with Gauguin, however, after two months the relationship began to deteriorate. Vincent admired Gauguin and wished to be treated as his equal, however, Gauguin was rather arrogant and full of criticism, which was frustrating for Vincent and led to many quarrels. Every day, Vincent feared Gauguin would leave him, describing the situation as one of “excessive tension”. Eventually, Vincent’s fear became a reality.

It is difficult to determine exactly what happened next because Van Gogh had no recollection of the events. Gauguin claimed they had been cooped up in the house due to several days of heavy rain, which led to much bickering culminating in a huge argument. To cool off, Gauguin left the house to go for a walk, however, Vincent, presumably mistaking this action for abandonment, “rushed towards me, an open razor in his hand”. That night, Gauguin stayed in a hotel rather than returning to the Yellow House.

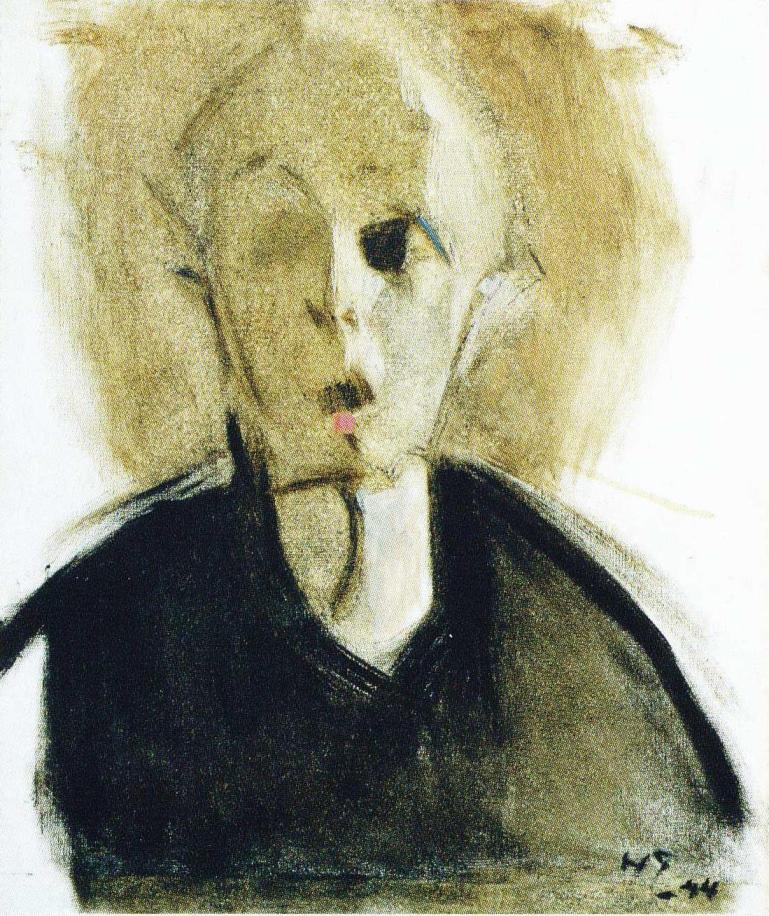

Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889

Alone in the house, Van Gogh was plagued by “voices” and cut off his left ear with the razor. Whether this was wholly or partially is now unknown since there are discrepancies between the sources from the time of the incident. Van Gogh bandaged his heavily bleeding wound, wrapped the ear in paper and delivered it to a woman at a brothel he and Gauguin frequented. Vincent was discovered unconscious by a policeman the following morning, who took him to the local hospital.

Van Gogh was diagnosed with “acute mania with generalised delirium” and remained in the hospital for some time. Although Gauguin had returned to Paris, the artists put the event to one side and continued to correspond through letters. They proposed to form a studio in Antwerp when Van Gogh was well but they never had the chance.

On 7th January 1889, Van Gogh returned to the Yellow House, however, he was still suffering from hallucinations. Some sources claim Vincent tried to poison himself, whereas others say this was one of his delusions; nonetheless, concerned for his welfare, inhabitants of Arles demanded that he was forcibly removed from the house. Vincent found himself back in the hospital, eventually agreeing to voluntarily admit himself to the asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

Corridor in Saint-Paul Hospital, 1889

The Starry Night, 1889

Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, 1890

Van Gogh stayed in the asylum for about a year, during which time he was allowed to paint. The clinic and its gardens were Vincent’s primary sources of inspiration as were patients and doctors. The Starry Night, one of Van Gogh’s most famous works, was painted in the hospital grounds.

Letters continued to be sent back and forth between Theo and Vincent as well as a few friends. Since there was a limited amount of artistic inspiration in the hospital, Theo sent his brother prints of famous artworks from which to copy. Some of Vincent’s favourite artists to study included Jean-François Millet (1814-75), Jules Breton (1827-1906), Gustave Courbet (1819-77) and Gustave Doré (1832-83).

Prisoners’ Round (after Gustave Doré), 1890

Two Peasant Women Digging in a Snow-Covered Field at Sunset, (after Jean-François Millet), 1890

Van Gogh’s letters to his brother became increasingly sombre and he suffered a relapse between February and April 1890. During this time, he felt unable to write, however, there are a few small paintings dated around this time. Two Peasant Women Digging in a Snow-Covered Field at Sunset was one of these, based on an artwork by Millet.

Meanwhile, Van Gogh’s paintings were beginning to attract attention and he was invited to submit some of his paintings to an avant-garde exhibition in Paris. Whilst some people were critical of his work, others defended Van Gogh’s style and he was soon invited to participate in an exhibition with the Artistes Indépendants in Paris. Claude Monet (1840-1926) declared Van Gogh’s work was the best in the show.

Almond blossom, 1890

It was not the success of the exhibition that buoyed Van Gogh’s motivation to write and paint again but rather the news from Theo that his wife Jo (1862-1925) had born a son, Vincent Willem van Gogh. “How glad I was when the news came… I should have greatly preferred him to call the boy after Father, of whom I have been thinking so much these days, instead of after me; but seeing it has now been done, I started right away to make a picture for him, to hang in their bedroom, big branches of white almond blossom against a blue sky.”

Almond Blossom is unlike any of Van Gogh’s previous paintings. The blue sky is more realistic than the swirly backgrounds of his recent works. The branches of the tree are outlined in black, which was a feature Van Gogh admired in Japanese paintings.

Wheatfield with Crows, 1890

By May 1890, Van Gogh was deemed well enough to be discharged from Saint-Rémy, however, he had no home to which to return. Instead, he moved to the Paris suburb of Auvers-sur-Oise to be closer to both Theo and his doctor, Dr Paul Gachet (1828-1909). Van Gogh continued painting, absorbed by “the immense plain against the hills, boundless as the sea, delicate yellow” and “vast fields of wheat under turbulent skies”. When writing to Theo about one of his final oil paintings, Van Gogh said that they represented “sadness and extreme loneliness” and “tell you what I cannot say in words”.

On 27th July 1890, Van Gogh failed to return to his lodgings for his evening meal. His arrival later in the night revealed the reason for the delay; Vincent had shot himself in the chest with a 7mm Lefaucheux à broche revolver. Although there was no damage to any vital organs, there was no surgeon in the area to remove the bullet. Two local doctors did the best they could and left him at home where he was joined by Theo. Vincent was in good spirits but soon began to suffer from an infection. Not long after his final words, “The sadness will last forever”, Vincent van Gogh passed away in the early hours of 29th July.

“… and then it was done. I miss him so; everything seems to remind me of him.”

– Theo to his wife Jo, 1st August 1890

Van Gogh was buried the next day in the municipal cemetery of Auvers-sur-Oise and was joined by Theo the following year. Theo had been ill and worsened after the death of his brother. Initially, Theo was buried in Utrecht, however, his wife had his body exhumed and reburied beside his beloved brother. Jo knew how much Vincent meant to Theo and it is thanks to her that Vincent’s letters have been preserved and made public. Although other family members were unhappy about this, without the letters Vincent may never have been as celebrated as he is today.

-

-

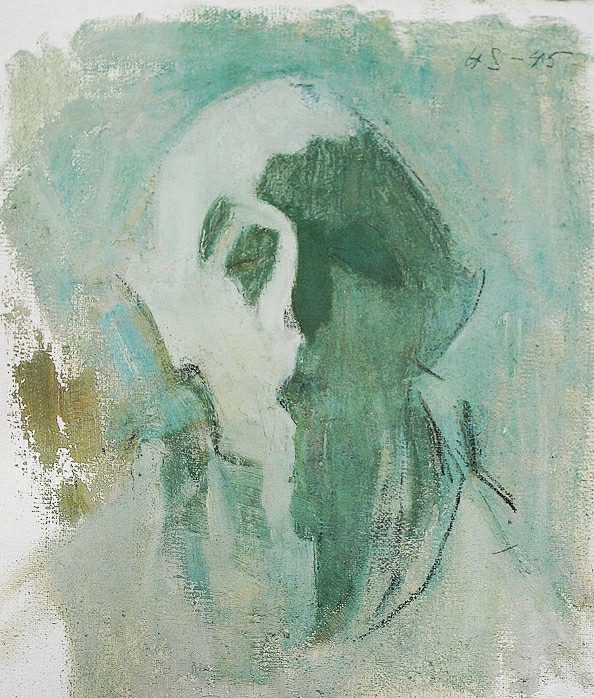

Head of the Dead Casagemas – Picasso, 1901

-

-

Homage to Van Gogh – David Hockney, 1988

-

-

Red Virginia Creeper – Edvard Munch, 1900

Van Gogh’s story does not end with his death but continues through the lives of millions of people around the world for whom he is still a source of inspiration. Well-known artists have been influenced by Van Gogh, including Pablo Picasso, David Hockney, Piet Mondrian, Henri Matisse, Edvard Munch and Francis Bacon.

Contemporary artists are also fans of Van Gogh and attempt to recreate his style, for example, a Van Gogh-esque painting of Donald Duck that appeared on a Walt Disney magazine in 2015.

The Meet Vincent Van Gogh Experience proves how much Vincent van Gogh is loved and appreciated. His life was full of mental anguish and unhappiness, which ended prematurely before he had the chance to witness his success. His tragic story is part of the draw to the artist, however, Van Gogh’s highly recognisable works are appreciated all over the world for their uniqueness.

With a museum named after him, Van Gogh has excelled beyond his expectations and it is a shame that he will never know. The Meet Vincent van Gogh Experience allows people to learn more about the artist, to discover his story, and to appreciate his work with a greater understanding.

Tickets for the Meet Vincent van Gogh Experience vary between £16.50 and £18.50 for adults, and £12.50 and £14.50 for children. Time slots and tickets can be purchased via Ticketmaster in advance. The experience will be open every day until Thursday 21st May 2020.

Ever yours,

Vincent

My blogs are now available to listen to as podcasts on the following platforms: Anchor, Breaker, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts and Spotify.

If you would like to support my blog, become a Patreon from £5p/m or “buy me a coffee” for £3. Thank You!