Leonardo da Vinci – attributed to Francesco Melzi

It has been 500 years since Leonardo da Vinci died on 2nd May 1519, aged 67, at Amboise in central France. To mark the anniversary, the Royal Collection Trust has curated an exhibition that brings together over 200 of Leonardo’s greatest drawings. Not only are these works of art, but they served as thought processes of the superhuman polymath. With interests including painting, architecture, anatomy, engineering and botany, these sketches provide an exceptional insight into the workings of Leonardo’s mind.

The first drawing featured in the exhibition is a portrait of Leonardo da Vinci with long wavy hair and beard. This is the only surviving representation of the influential genius to survive today, however, it is not a self-portrait. It has been accredited to one of Leonardo’s pupils, Francesco Melzi (1493-1570) who was bequeathed all of his teacher’s drawings. Melzi kept tight hold of every scrap of paper that Leonardo had drawn on, almost as if they were relics. After his death in 1570, they were passed onto the Italian sculptor Pompeo Leoni (1533-1608) who painstakingly mounted them all into at least two albums. By 1670, one of the albums had found its way into the hands of King Charles II (1630-85) and the drawings have remained in the Royal Collection ever since. In the early 1900s, the pictures were removed from the album, stamped with the cypher of Edward VII (1841-1910) and individually framed. There are around 550 of Leonardo’s drawings in the Collection, 200 of which have been specially selected for this exhibition.

Leonardo was born in 1452 near the town of Vinci in Florence, Italy. He was the illegitimate son of a lawyer, Piero da Vinci, and a peasant girl called Caterina. He was raised by his paternal grandfather, however, little else is known about his childhood. Leonardo was educated in the studio of Andrea del Verrocchio (1435-88) and, by the age of 20, was working as a painter in Florence. In 1480, Leonardo received his first big commission, the Adoration of the Magi, however, this remained unfinished by the time he moved to Milan the following year.

As a juvenile artist, Leonardo learnt how to draw using metalpoint. This was a stylus made from either lead, silver, copper or other metals. It was a laborious technique for, in order to make a mark on the paper, the surface had to be coated with a mixture of ground bone ash and glue. By the late 1490s, the method had fallen out of use across Italy.

The older drawings in the exhibition are examples of the metalpoint technique. These include a profile of a young woman wearing a cap, which may have been a preparatory study for a painting that is now lost. Leonardo also used this drawing method to practice and work out compositions before picking up a paintbrush. A sheet of paper containing a study of hands shows how Leonardo experimented with different positions before settling on the one that created the effect he was after.

Leonardo da Vinci – Virgin of the Rocks, 1503-1506

In 1483, Leonardo received the commission to paint what is now known as the Virgin of the Rocks for a church in Milan. He painted two versions, one which was never installed and now resides in the Louvre in Paris, and the other that was put in place in 1508. The painting has since been moved and hangs in the National Gallery in London.

Leonardo began working on the Virgin of the Rocks by producing a number of preparatory studies. One of these, which is on display, is for the drapery of a kneeling figure. Comparing this drawing to the final painting, it can be noted that the composition changed slightly, however, the study was an experimental sketch for the pose of the angel on the right of the Virgin Mary. The drawing has been produced with a series of brushstrokes, fine hatching and cross-hatching, which was almost unique to Leonardo at the time. Being left-handed, his strokes slant at a different angle to the majority of right-handed artists.

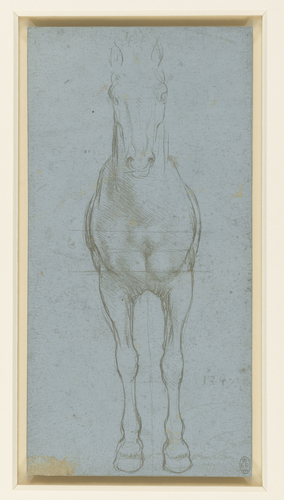

A horse divided by lines c.1490

During the 1480s, Leonardo entered the service of Ludovico Sforza (1452-1508), the ruler of Milan. He commissioned Leonardo to design a bronze equestrian monument in honour of his father Francesco (1401-66), the founder of the Sforza dynasty. Leonardo began by studying and drawing horses in various positions, such as rearing and walking, from all angles. When satisfied with his design, he built a bigger-than-lifesize model out of clay in order to construct the mould ready for casting. Unfortunately, the bronze needed for the monument was requisitioned in order to build a canon, thus the project was suspended.

Five years later, Sforza was deposed by the French and Leonardo’s clay model was used for target practice by the troops and ultimately destroyed.

Leonardo’s drawings from this period also include designs for weapons, armour and grotesque figures. The latter deliberately distorted the ideals of beauty at the time and, perhaps, are some of the first examples of caricatures.

- Studies for the Last Supper

- The head of Judas c.1495

- The head of St Philip c.1495

- The head of St James c.1495

- The arm of St Peter c.1495

Before Sforza lost his position as Duke of Milan, he commissioned what would become one of Leonardo’s greatest works, second only, perhaps, to the Mona Lisa. Leonardo was tasked with painting a mural of The Last Supper onto the wall of the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. This painting represents the Passover meal Jesus had with his apostles not long before his arrest as written in the Gospel of John.

After he had said this, Jesus was troubled in spirit and testified, “Very truly I tell you, one of you is going to betray me.”- John 13:21 (NIV)

It is thought that Leonardo produced hundreds of sketches, refining his ideas for the final painting, however, only a few survive. Only one compositional sketch remains, showing a couple of ideas he experimented with. The challenge was to fit thirteen figures around a table whilst giving each one a distinctive characteristic. In one sketch, Judas is depicted at the end of the table and in another, he is standing to receive the bread from Christ. In the final painting, Judas has been integrated into the group of disciples.

The exhibition displays some of Leonardo’s initial sketches of some of the disciples, one of which is Judas. The traitor has a hooked nose, close-set lips and a muscular neck. His head is turned away from the viewer to look at Christ in mild surprise. In the painting, Judas’ facial expression appears to reveal his evil intent, however, it is thought this has been added by restorers at a later date.

The sketch of St Philip shows the disciple’s youth, emphasised by his long wavy hair and smooth face. St James also appears to be young with a similar hairstyle. The latter sketch, however, has been produced more rapidly than the others, suggesting it was drawn from a live model. Leonardo also practised the drapes of the clothing the disciples wore, for example, the sketch of St Peter’s arm who, dressed in thick fabric, leans over Judas’ shoulder in the final painting.

- A Bust of A Child in Profile c.1495-1500

- Studies for the head of Leda c.1505-6

- Studies for Christ as Salvator Mundi c.1504-8

Leonardo briefly returned to Florence at the beginning of the 16th century. By now, he was using natural red and black chalks to produce his sketches, as can be seen in the delicate bust of a young child. This is likely a drawing of the Christ Child, although, no evidence of a painting featuring the same figure exists. Also in orangey-red is a study of drapery for the recently rediscovered painting of Christ as the saviour of the world, Salvator Mundi.

In a combination of black chalk or charcoal and ink are a few studies for the head of Leda for the lost painting of Leda and the Swan. In Greek mythology, Leda was a queen of Sparta who was seduced by Zeus in the form of a swan. Leda then bore two eggs from which hatched two sets of twins: Helen and Polydeuces, and Castor and Pollux.

The painting, which was destroyed in the eighteenth century, is thought to be the only image of the female nude Leonardo produced; however, he was far more interested in the elaborately coiled and braided hair and plants in the foreground than her body. The exhibition also displays a number of plant sketches that indicate Leonardo’s scientific interest in botany.

One of Leonardo’s main reasons for returning to Florence was to paint a huge mural in the Palazzo della Signoria to represent the Battle of Anghiari. The painting had been commissioned by the government to show the victory over the Milanese in 1440. Unfortunately, Leonardo never had the chance to complete the painting and the progress he had made was later destroyed.

What has survived, however, are some of Leonardo’s studies of horses and riders. In some, the horses are running at full gallop, their manes billowing in the wind. In others, the artist has focused on the powerful expressions on the horses’ faces, their lips drew back and eyes wild.

Although Leonardo had nothing to show for the Battle of Anghiari commission, it rekindled an old interest of his: anatomy. Leonardo had begun studying anatomy many years before, however, his sketches were largely inaccurate. He had no knowledge of the circulatory system and believed that veins distributed nutrition to the liver. The heart, he assumed, produced the body’s spirit, which was pumped around the body via the arteries.

From around 1506, Leonardo had access to human corpses from which to study in detail. He was on good terms with a handful of physicians who regarded Leonardo as an anatomist. In the winter of 1507-8, Leonardo performed his first post-mortem on the body of an elderly man in the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence. He recorded his findings in a series of notes and detailed drawings.

During his first dissection, Leonardo discovered the gastrointestinal tract and appendix. In writing, written backwards in mirror-image so that other people could not easily plagiarise his ideas but more so because, being left-handed, he was less likely to smudge the ink, Leonardo has produced the first description of this structure in Western medicine. He mentions the process of urine from the kidneys through to the bladder amongst other findings.

Leonardo also dissected animals, recording details of their internal organs, such as the lungs. Whilst claiming to have dissected thirty humans, he never performed an autopsy on a female. Nonetheless, he attempted to produce a diagram of the cardiovascular system and organs of a woman by combining the knowledge gained from other dissections, including animal, and ancient beliefs, such as a spherical, seven-chambered uterus.

Although recalled back to Milan where he served French occupiers in a number of ways for about seven years, he continued to work intensively on the anatomy. In 1513, Leonardo moved to Rome under the patronage of Giuliano de’ Medici (1479-1516), brother of Pope Leo X (1475-1521). Despite wanting to continue with his studies, he was not allowed to conduct any more dissections and his anatomical studies came to a halt.

Leonardo was ahead of his time with his anatomy discoveries and his drawings and notes were not fully understood until the 1900s. Although his work did not impact modern developments in biology, in hindsight it is clear that the Renaissance anatomist had learnt the scientific accuracies about the structure of the human body long before anyone else.

One sheet of sketches and jottings made by Leonardo show the musculature in an arm and the veins flowing from the body to the limb. Another sketch details the skeletal structure, revealing the spinal column, pelvis, arm bones and leg bones. There are a few errors on this particular page, for example, an elongated shoulder blade, but on the whole, it was an unprecedented drawing of a human skeleton.

In a heavily annotated drawing of muscles and tendons of a lower leg and foot, Leonardo debunked the theory that contraction of the muscles involved inflation with systemic air. In his drawing of a foetus in a womb, however, he had no real knowledge of the insides of a female’s reproductive system and yet he produced a drawing that looks close to the truth. Leonardo was intrigued that a foetus could fit in the uterus and so, using his knowledge of a cows placenta drew a curled up foetus with the umbilical cord wrapped around the crossed legs. Apart from being in the breech position, this illustration of the foetus is not too dissimilar to contemporary diagrams.

The Chateau of Amboise c.1517-19 – attributed to Francesco Melzi

From Rome, Leonardo travelled to France after accepting an offer of employment at the court of Francis I (1494-1547), the king of France. By now, Leonardo was 64 years old and he and his assistants were still painting his future famous works including St Anne and Mona Lisa. Settling at Amboise in the Loire valley, Leonardo held the position of painter, engineer and architect to the king. He mainly worked as a designer, producing sketches of architecture, costumes and equestrian monuments. The sketch of the Chateau of Amboise on display, however, was not produced by Leonardo’s hand. It is most likely the work of one of his assistants, the aforementioned Francesco Melzi. Although the style is similar to Leonardo’s the direction of the hatching indicates it was produced by a right-handed artist.

Francis I was a keen party-goer and held several lavish entertainments, for which Leonardo designed costumes. Leonardo went to town with the detail producing designs rich with ribbons, fringes, furs, quilted sleeves and breeches. Clothing ranged from mercenary soldiers’ uniforms to fools and even prostitutes.

Not only did Leonardo design costumes, but his drawings also showed the characters in action, for example, a young man on horseback complete with a lance. This showed how the material would fall as the body moved and may even have been a help to the seamstress. Not all the costumes were elaborate, however; his sketch of a masquerader dressed up as a prisoner involved rags and shackles.

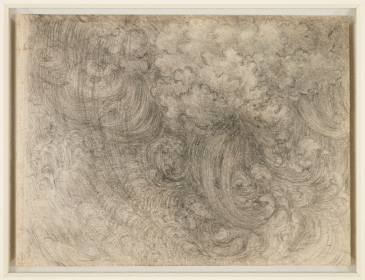

Toward the end of his life, Leonardo became preoccupied with cataclysmic storms, floods and man’s futile struggle against the overwhelming forces of nature. Art historians tend to believe Leonardo was extremely aware of the limited time he had left and was reflecting on some of his greatest creations, which had been destroyed in front of his very eyes, i.e. the equestrian monument commissioned by Sforza. Leonardo understood the impermanence of the world, having studied human anatomy, dissected dead bodies and examined plant and animal life for a number of years.

These sketches of deluges, however, were not created by an elderly man suffering from despair. They were drawn with the eye of a scientist, showing the optical qualities of cloud, rain, water and smoke.

A description of a deluge, with marginal sketches c.1517-18

As well as drawing, Leonardo wrote detailed instructions about how to draw an accurate deluge.

Let there first be shown the summit of a rugged

mountain surrounded by valleys. From its sides

the soil slides together with the roots of bushes,

denuding great areas of rock. And descending from

these precipices, ruinous in its boisterous course, it

lays bare the twisted and gnarled roots of large trees,

throwing their roots upwards; and the mountains,

scoured bare, reveal deep fissures made by ancient

earthquakes. The bases of the mountains are covered

with ruins of trees hurled down from their lofty

peaks, mixed with mud, roots, branches and leaves

thrust into the mud and earth and stones.And into the depths of a valley the fragments of

a mountain have fallen, forming a shore to the

swollen waters of its river, which has burst its banks

and rushes on in monstrous waves, striking and

destroying the walls of the towns and farmhouses

in the valley. The ruin of these buildings throws up

a great dust, rising like smoke or wreathed clouds

against the falling rain. The swollen waters sweep

round them, striking these obstacles in eddying

whirlpools, and leaping into the air as muddy

foam. And the whirling waves fly from the place of

concussion, and their impetus moves them across

other eddies in a contrary direction […]The rain as it falls from the clouds is of the same

colour as those clouds, in its shaded side, unless the

sun’s rays break through them, in which case the

rain will appear less dark than the clouds. And if the

heavy masses of ruined mountains or buildings fall

into the vast pools of water, a great quantity will

be flung into the air, and its movement will be in a

contrary direction to that of the object which struck

the water; that is to say, the angle of reflection will

be equal to the angle of incidence.Text adapted from Leonardo da Vinci: A life in drawing, London, 2018

This is the writing of a man still of sound mind; a scientist and an artist whose skills complement each other rather than contrast. Leonardo was a great thinker both visually and intellectually, and there has arguably not been anyone since who matches his genius.

By 1518, Leonardo’s health was deteriorating and reports state that he had lost the use of his right arm, which suggests he may have suffered a stroke. His weakness is evident in one of his final sketches, a portrait of an old, bearded man, which whilst not a literal self-portrait may at least be an indication of how he viewed himself: lank hair and rheumy eyes. The chalk lines are shorter and more hesitant than Leonardo’s previous work, suggesting he did not have full control over the chalk.

Leonardo da Vinci passed away at Amboise on 2nd May 1519, leaving all his loose sheets and notebooks to Francesco Melzi. Due to Melzi’s care and protection, and of those who handled them afterwards, the drawings have survived to today, where we can appreciate an insight into the greatest mind of the Renaissance.

The exhibition Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing does not display any of Leonardo’s famous works. There are no paintings or complete artworks. Instead, the 200 or so sketches piece together the real man: the artist, the engineer, the botanist, the anatomist, the scientist, the mathematician, the inventor, the geologist, the astronomer, the writer, the historian, the cartographer, the greatest man of all time. We are extremely lucky to have the opportunity to view these drawings when many of his major works have been lost or destroyed.

The chance to view the exhibition of Leonardo’s work in London is possible at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace until Sunday 13th October 2019 after which it will move to the Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse. Tickets are £13.50 for adults and it is highly recommended that they are booked in advance online.

My blogs are now available to listen to as podcasts on the following platforms: Anchor, Breaker, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts and Spotify.

If you would like to support my blog, become a Patreon from £5p/m or “buy me a coffee” for £3. Thank You!

Two great masters, Leonardo and Hazel combining their undoubted talents. A most interesting read and really enhances the pleasure of going to the exhibition. Hazel, once again you gave triumphed, thank you for sharing your, writing prowess.

Another great read Hazel. I have actually visited the house(cottage) which Francis I provided for him. Good to be reminded of Leonardo’s amazing talent.

Pingback: Simeon Investigates Covent Garden | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: The Virgin of the Rocks | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Unicorns: A True Story | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Spot the Cat | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Alma Mahler | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Raphael | Hazel Stainer