“The possibilities of paint are never-ending.”

– Frank Bowling, 2017

For the first time in his career, the 85-year-old Frank Bowling has been honoured with a major retrospective of his life and artwork by Tate Britain in London. The exhibition offers the chance to view the best of Bowling’s works and discover an artist that many know little or anything about. His large canvases dominate the rooms and show off his unique techniques, including his “Map Paintings” and “Poured Painting”. Being the first black man to be elected to the Royal Academy of Arts, it is surprising Frank Bowling is not better known.

Richard Sheridan Patrick Michael Aloysius Franklin Bowling, shortened to Frank, was born on 26th February 1934 in Bartica, British Guiana (now Guyana). His father, Richard Sheridan Bowling, was a police paymaster and his mother, Agatha Elizabeth Franklin Bowling was a seamstress. When Frank was six-years-old, the family moved to New Amsterdam on the Berbice River in the north-east of the country where his mother established the Bowling’s Variety Store. Frank grew up helping his mother, which included washing the feet of beggars who came to the store for a meal. His father, on the other hand, showed him very little love.

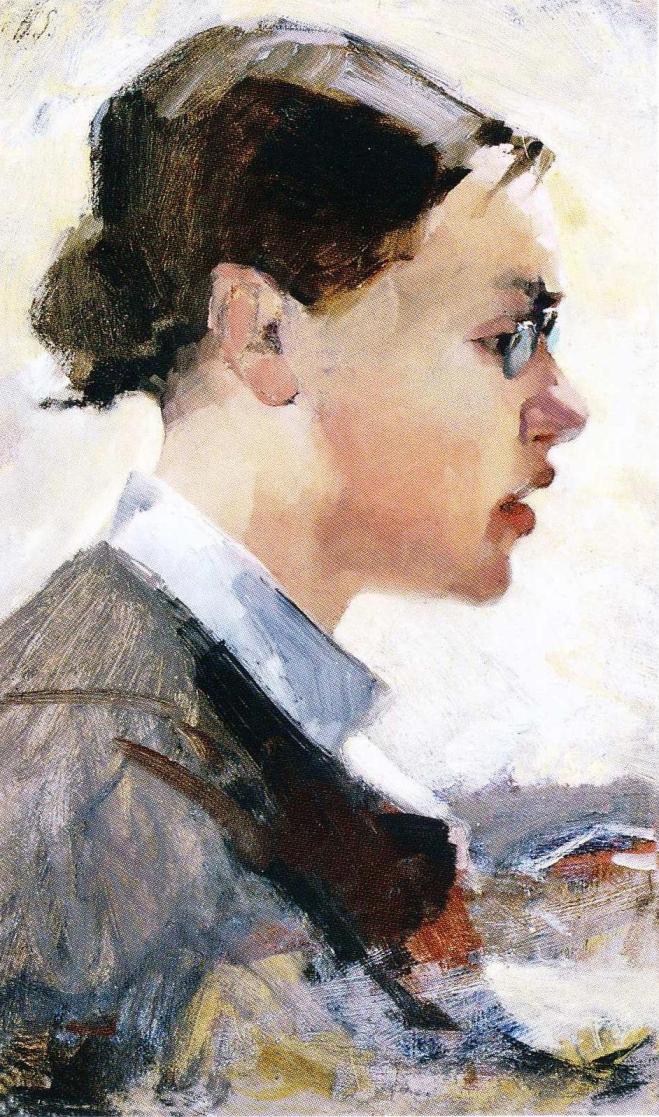

In 1953, Bowling flew to England to live with an uncle and finish his education. He dreamed of becoming a writer or poet but soon after he had finished school, he was drafted into the Royal Air Force for two years. After this, the young South American decided to train as a painter, first enrolling at the Regent Street Polytechnic, then the Chelsea School of Art. In 1959, Bowling was awarded a scholarship to the Royal College of Art’s (RAC) Painting School where he became acquainted with other talented students, including David Hockney (b.1937) and Ronald Brooks Kitaj (1931-2007).

In 1960, Bowling was expelled from the college after marrying Paddy Kitchen, a writer and art critic, who was a member of staff at the time. Despite this, Bowling was determined to persevere with his art and enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London for one term. Here, he began to develop a taste for the artist Francis Bacon (1909-92), which is evident in his earlier work. Fortunately, the RAC was persuaded to readmit Bowling, which is where he finished his art training. His letter of readmission is on display in the exhibition.

Birthday, 1962

Bowling’s penchant for abstract art was clear during his time at art college. When the students were asked to produce a painting on the theme of birthdays, Bowling did not go down the obvious route. Instead, he produced an impressionistic oil painting of a woman giving birth. When he was younger, Bowling witnessed a neighbour giving birth and the intense pain he observed stayed in his mind for many years.

Titled simply Birthday (1962), Bowling appropriated Francis Bacon’s style of composition, including line work and brushwork. Whilst the open window is fairly lucid and geometric, the figure of the woman in labour is blurred and distorted.

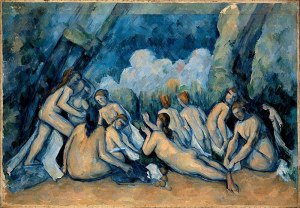

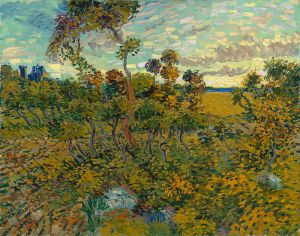

As well as Francis Bacon, Bowling was influenced by a number of artists he met. In 1961, he visited New York where he viewed work by people such as Jackson Pollock (1912-56). Pollock’s technique of pouring or splashing liquid household paint onto a horizontal surface was something Bowling would incorporate into his own work later in life.

Unfortunately, many of Frank Bowling’s early works have been destroyed or are missing. He worked in many different London studios during the early 1960s and many paintings were left behind or mislaid whenever he moved. Amongst the missing is a painting Bowling produced in response to a political event. In 1961, the Democratic Republic of the Congo earned their independence from Belgium and installed their first president, Patrice Lumumba (1925-61). Martyrdom of Patrice Lumumba was produce after the president was murdered later that same year.

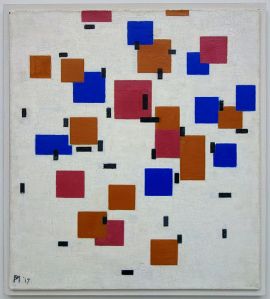

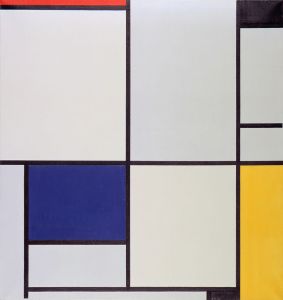

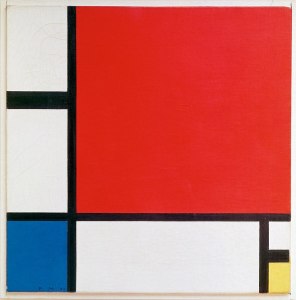

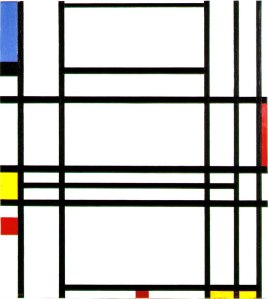

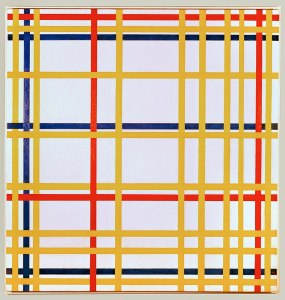

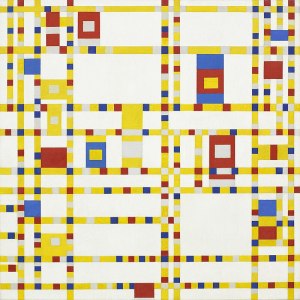

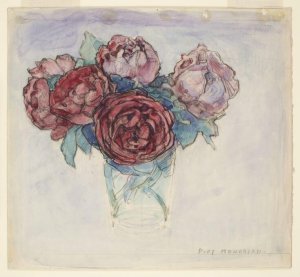

The year 1962 was quite significant for Frank Bowling. Firstly, his eldest son Dan was born to Paddy Kitchen, shortly followed by his second son Benjamin to another woman, Claire Spencer. Evidently, his marriage to Paddy did not last long. In the same year, Bowling graduated from RCA after writing a thesis about Piet Mondrian (1872-1944). The Dutch painter’s style was another influence for Bowling’s work.

On graduating, Bowling was awarded the silver medal for painting, with David Hockney winning gold. He was offered a travelling scholarship to Rome but requested he visit Barbados, Trinidad and Guyana instead. This was his first trip home in over a decade.

Toward the end of 1962, Bowling held his first major exhibition at Grabowski Gallery in London. His painting Birthday was purchased by the Arts Council and he was able to meet lots of new people who would become friends and mentors.

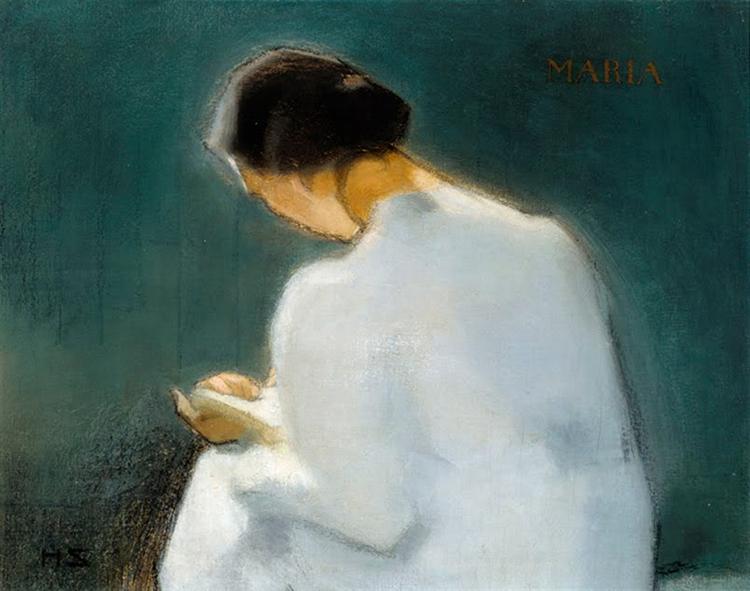

Swan I, 1964

Big Bird, 1964

In his early career, Bowling frequently produced artworks in response to events or things he had witnessed. He produced a series of paintings titled Swan, which was based upon a dying swan drenched in oil he had come across on the River Thames. He used thin, rhombus-shaped canvases for these paintings, an idea he took from an American painter, and filled them with coloured stripes, which was a concept inspired by someone else. His dying swans are painted on top of the geometrically decorated canvases in a less precise manner, almost as if they are moving in an attempt to escape.

Bowling’s swan theme continued in his large scale painting Big Bird (1964). The pattern of the background, reminiscent of Mondrian, is a stark contrast to the expressively abstract birds. In 1965, this painting was submitted to the First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal where it won the grand prize for painting. Bowling was not overly keen about participating in the exhibition because he did not want to be categorised as a Black painter. He wanted to be regarded as an artist without his ethnicity taking centre stage. Later in life, he remarked that he felt suffocated by his background and frustrated that the art world focused more on his skin colour than his paintings. He observed that Guyana often felt like the heavy rock the Greek king Sisyphus was doomed to repeatedly roll up a hill.

Cover Girl, 1966

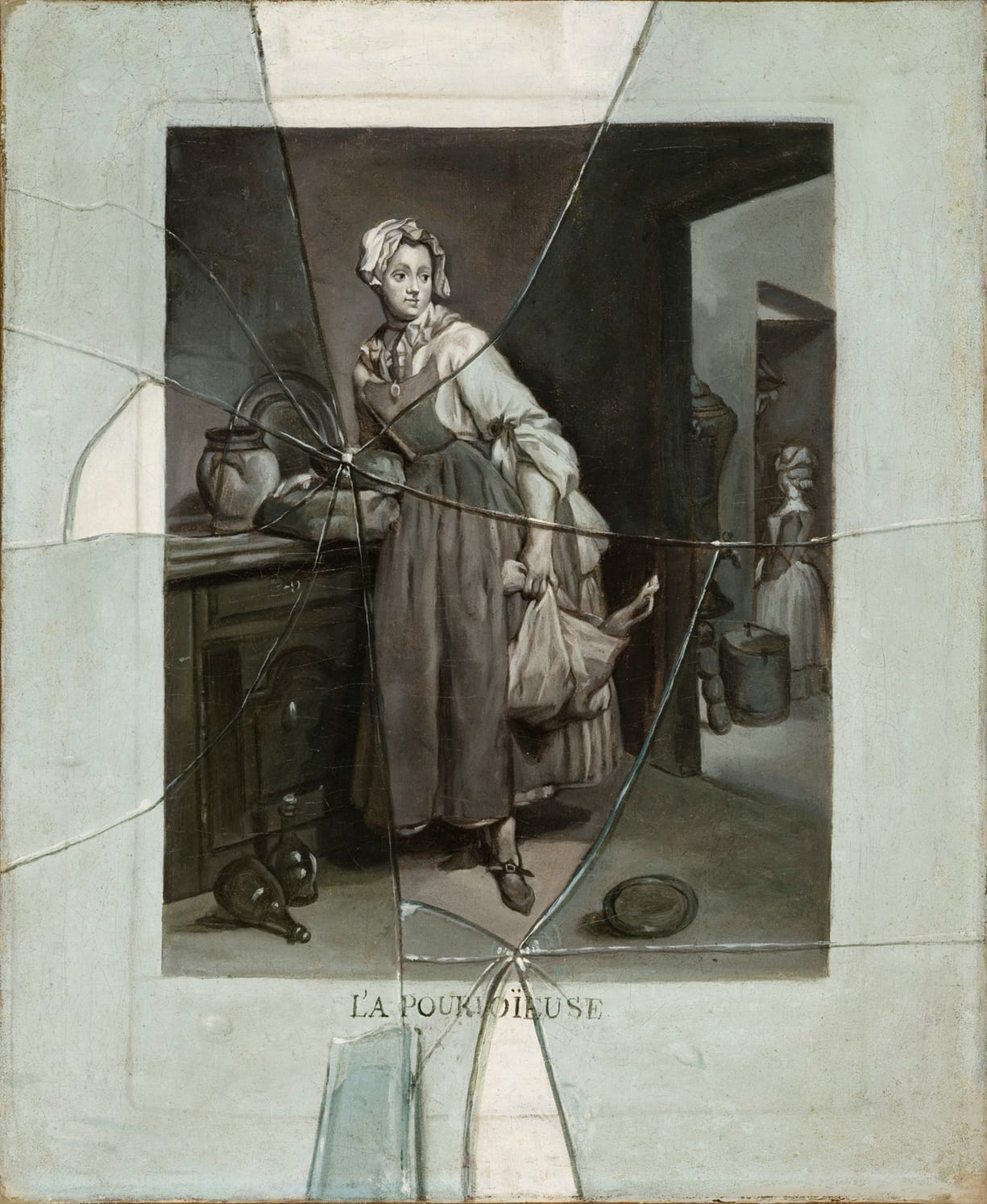

Mirror, 1964-6

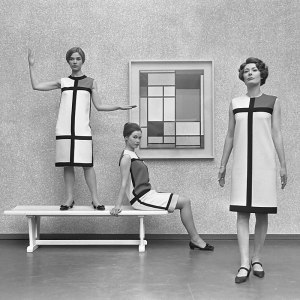

Despite his aversion to being remembered for his geographic and ethnic backgrounds, Bowling’s life in Guyana featured heavily in his paintings, particularly his childhood home. Bowling continuously experimented with different pictorial approaches and techniques, which included photography and silkscreen. Using photographs of his childhood home, Bowling created a stencil that he could repeatedly use to print the image onto his canvases. In his painting Cover Girl (1966), for example, the image of his old house floats in the background. The “cover girl” in question is based on a photograph of the Japanese model Hiroko Matsumoto (1926-2003) that Bowling found in a copy of the Observer. The dress is inspired by the designs of the French fashion designer Pierre Cardin (b.1922) and the hairstyle by British-American hairstylist Vidal Sassoon (1928-2012).

Painted at a similar time was the carefully worked out composition Mirror (1964-6). Whilst it contains many similar features, for example, the geometric backgrounds and Bacon-esque figures, there is no screen print of Bowling’s childhood home. Instead, Bowling includes two portraits of himself, one standing at the bottom of the stairs and one swinging from the top. The figure in between is Paddy Kitchen to whom he was still married. This particular painting fuses together several different styles, suggesting a rebellion against convention.

By 1964, Bowling had a third son, Sacha, with yet another woman, Irena, who he later married, although they would eventually divorce. The same year, he returned to New York and became acquainted with abstract expressionist Jasper Johns (b.1930). As well as painting, Johns was a sculptor and included found objects on his canvases. This is another idea Bowling would take up later in his career.

Frank Bowling relocated to New York in 1966, the same time that his marriage to Paddy came to an end. The following year, he was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship, which helped him establish himself in America. He moved into a studio in SoHo, New York, where he lived and worked until 1975.

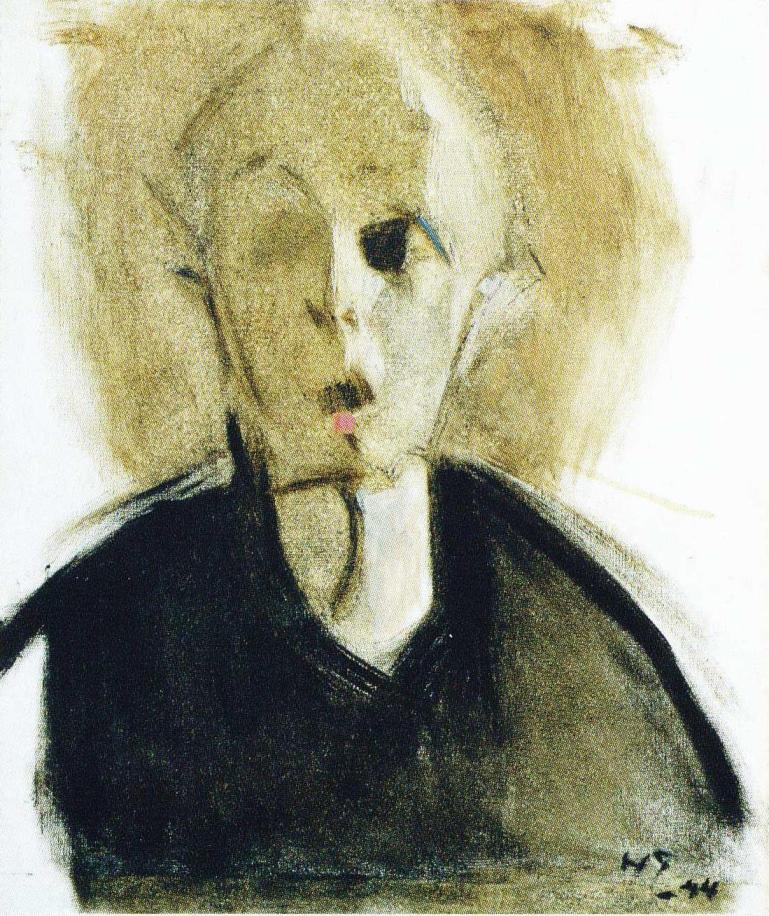

South America Squared, 1967

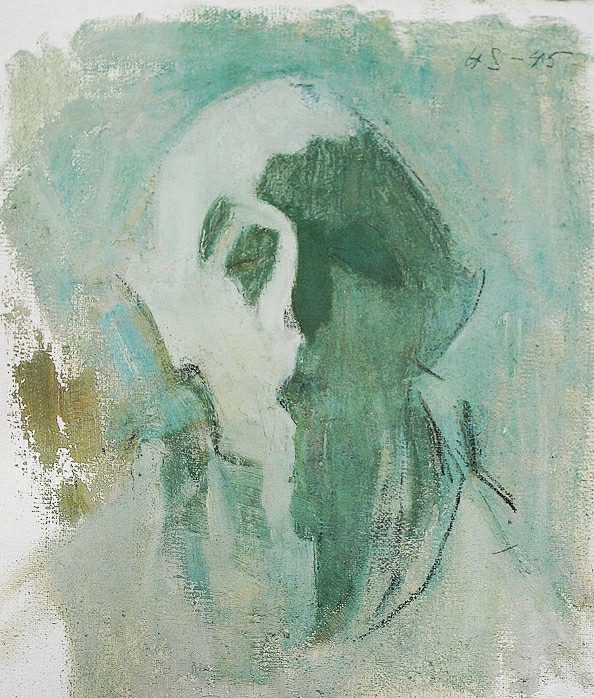

Polish Rebecca, 1971

Barticaborn 1, 1967

From 1967 until 1971, Bowling worked on what would become known as his “map paintings”. Tate Britain described these as “Fields of colour … overlaid with stencilled maps of the world and silkscreened images.” Bowling applied paint to the canvas by pouring or spraying, whilst using cut out stencils of various continents, particularly of the southern hemisphere, to block out certain areas, leaving a print of the shape in its place. He also used photographs of his sons or people he met in Guyana on a trip in 1968 with the photographer Tina Tranter.

South America Squared (1967) was the first “map painting” Bowling produced. The square shapes on the red canvas show that he had not quite left behind the influence of Piet Mondrian. To create the shape of South America, Bowling created a stencil with an epidiascope. This technique was introduced to Bowling by his American mentor Larry Rivers (1923–2002).

Polish Rebecca (1971) was named after Bowling’s friend Rita Reinhardt, the widow of the abstract painter Ad Reinhardt (1913-67). She had suffered tragedy during the Second World War when both her parents and sister were murdered during the Holocaust. Although the only “maps” represented are of South America and Africa, Bowling is hinting at the connection between the extermination of Jews in Europe with the dispersion of Jews in the southern regions.

Despite not wanting to be dictated by his past, all of Bowling’s “map paintings” are connected to his roots. Barticaborn I (1967), which was used on promotional material for the exhibition, refers to Bowling’s place of birth. Bartica is situated at the junction of three rivers: Cuyuni, Mazaruni and Essequibo. When visiting New Amsterdam with Tranter, they also went to Bartica to gather inspiration for Bowling’s work.

Ziff, 1974

Kaieteurtoo, 1975

At Swim Two Manatee, 1977-8

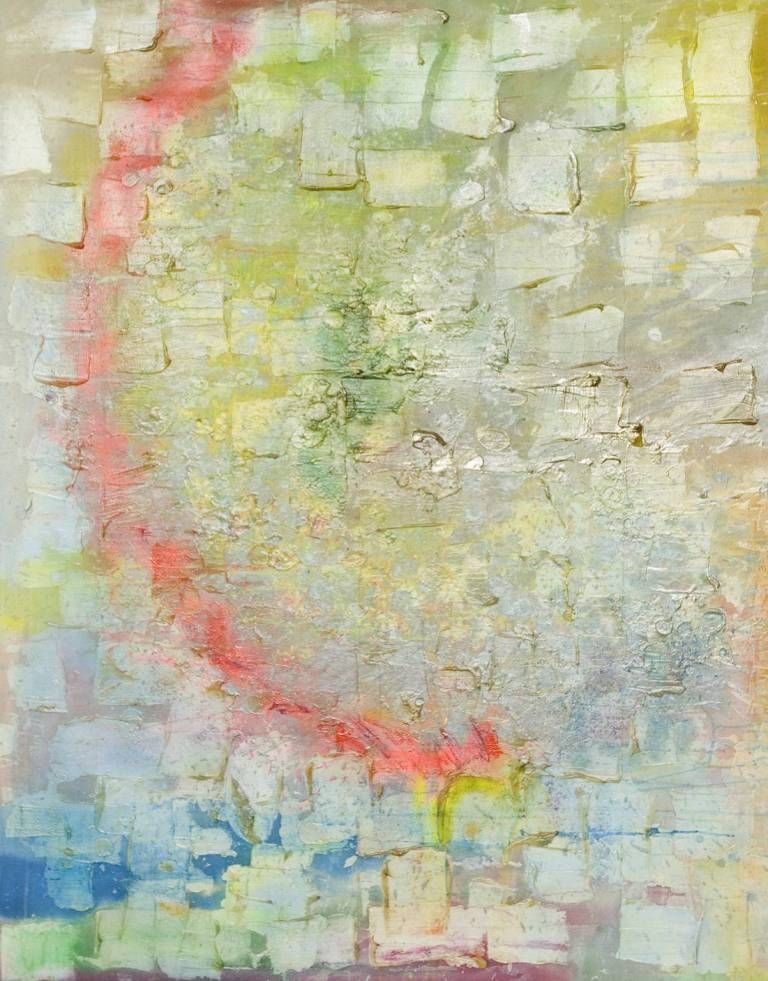

Around 1973, Bowling began using a new technique, which, although no mention was made in the exhibition, is likely inspired by the work of Jackson Pollock. This sudden change in his method may also be associated with the end of his marriage to Irena.

Bowling began experimenting by pouring different coloured paint onto a canvas and watching them merge together. In his New York Studio and later in his London Studio, which he took up in 1984 and still uses today, he set up a tilting platform, which allows him to pour paint from a height of two metres. The colours spill down the canvas, producing an unpredictable pattern.

All of Bowling’s “poured paintings” are a result of chance. He never began with an idea in mind; he let the flow of the paint take charge. He always titled the outcomes once he was finished, using the events of his daily life and the people he knew for inspiration. The ambiguously titled Ziff (1974) is a typical example of this style of work. Bowling filled the background with colour in a similar manner to his “map paintings” before applying liquid paint whilst the canvas was on the tilted platform.

Kaieteurtoo (1975) was named after having a conversation about the Guyanese tourist attraction Kaieteur Falls. This is the world’s largest single drop waterfall by volume of water flowing, which stands at a height of 226 metres and has a width of 113 metres. This name felt appropriate because the dripping paint almost resembles a cascade of water.

Toward the end of the 1970s, Bowling was applying a growing number of contrasting techniques. As well as using his tilting platform, he used combined washes of paint, spattering and splotching. Although these were similar methods to the aforementioned Pollock, there is no doubt that the results are unique to Frank Bowling. An example of this is At Swim Two Manatee (1977-8), which has a greater density than some of his previous works. By using these unpredictable techniques, Bowling said he was making “painting happen almost as if I didn’t do anything about it.”

Vitacress, 1981

Ah Susan Whoosh

Moby Dick, 1981

Due to the randomness of the applied paint, some of Frank Bowling’s works were the result of happy accidents. Vitacress (1981), for example, looks like a cosmic sky featuring a moon or planet. This round imprint, however, was the result of leaving a bucket on a drying canvas. Despite being unintentional, Bowling loved the result and used the “technique” in future paintings.

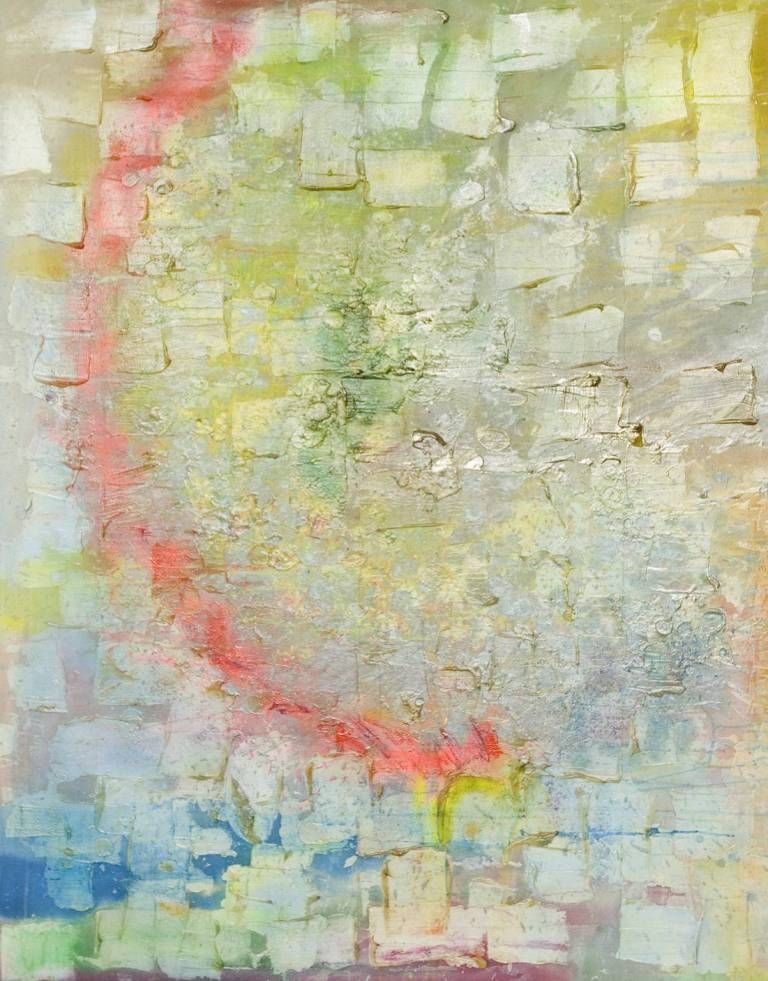

A selection of paintings at the Tate Britain is labelled “cosmic space”, however, this was never Bowling’s intention. As previously stated, Bowling never began an artwork with an idea in mind but let the flow of the paint dictate the outcome. By adding ammonia and pearlescence to the acrylics, the blending of colours produced a marbling effect, which in turn made them resemble cosmic space. Despite this, Bowling did not give them space-related titles, for instance, Ah Whoosh Susanna (1981).

As well as out-of-this-world results, some of Bowling’s artworks also resembled underwater scenes, for instance, Moby Dick (1981). The ammonia and turpentine also produced chemical reactions, which along with the water, altered the consistency and colour of the acrylic paint, allowing a smoother finish than other “poured paintings”.

-

-

Towards Crab Island, 1983

-

-

Wintergreens, 1986

-

-

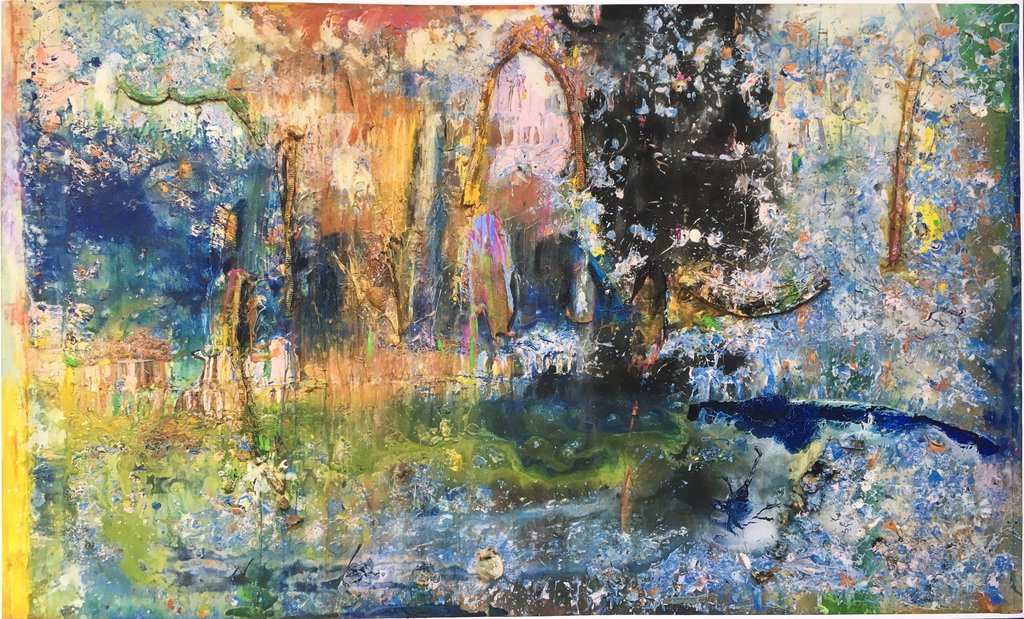

Spreadout Ron Kitaj, 1984-6

Bowling was still experimenting with techniques and media well into the 1980s. In 1983, he purchased a flat in Pimlico, not far from the Tate Britain, where he still lives today. He spent his time being with his sons, visiting Tate and working on his art. At Tate, he became familiar with J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable (1776-1837), whose use of colours sparked future ideas.

Perhaps inspired by Jasper Johns, Bowling began sticking found objects onto his canvases. These included plastic toys, packing material and oyster shells. As well as acrylic paint, he also used acrylic gel, acrylic foam, chalk, beeswax and glitter, all of which added to the texture of the final outcomes. Bowling tended to stick the items onto the canvas before applying paint using his pouring method. The weight and fluidity of the mixture occasionally dragged the items downwards into unplanned positions. Towards Crab Island (1983) is an example of this.

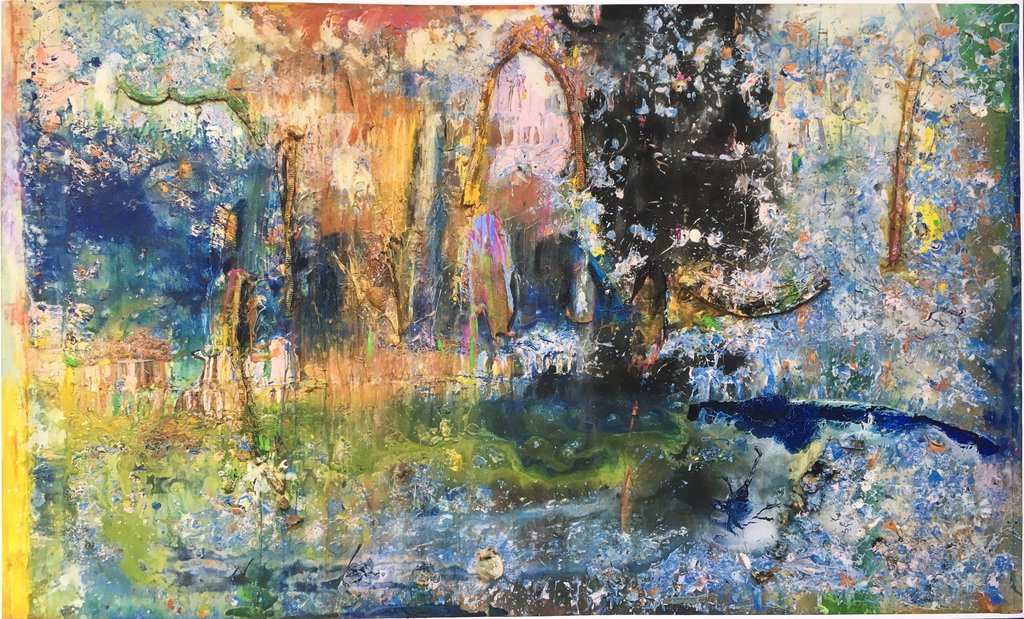

As always, Bowling named his paintings after they had been created and they were usually an unplanned experiment. During a summer residency at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Maine, however, Bowling was inspired by the rural landscape and forests, which he attempted to explore in his work. Without changing his method of working, Bowling produced Wintergreens (1986) using earthy colours to represent the scenery. He added several strips of acrylic foam, almost reverting to his geometric patterns from the 1960s. Although the paint obscures most of the found objects, there is apparently a cap of a film canister and a plastic toy owl hidden on the surface.

In 1987, Tate acquired its first painting by an artist of Afro-Caribbean descent: Frank Bowling’s Spreadout Ron Kitaj (1984-6). The title pays homage to Bowling’s fellow student at the RCA, R.B. Kitaj. Once again, Bowling created a design with acrylic foam, which was then dislodged when the paint was added. He describes these strips of foam as “the ribs of the geometry from which I worked.” Amongst the strips are bits of plastic jewellery, toys and oyster shells.

Great Thames II, 1989

Great Thames IV, 1989

Bowling’s engagement with colour came to a height at the end of the 1980s. With landscape artists such as Turner, Constable and Thomas Gainsborough (1727-88) in mind, Bowling began work on a series titled Great Thames. Two examples are on display in the exhibition. His choice of colour and luminous paint capture the play of light on the water at different times of the day.

“It’s exciting and challenging to work in London, Turner’s town, and the pressures of the weight of British tradition is exhilarating.”

– Frank Bowling

Sacha Jason Guyana Dreams, 1989

In 1989, Bowling was persuaded to participate in The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post War Britain at the Hayward Gallery. Despite his scepticism about being labelled by his ethnicity, curator Rasheed Araeen (b.1935) convinced him it was worth taking part. At this time, Bowling was thinking a lot about Guyana and his childhood, particularly following the death of his mother in 1988. Accompanied by his son Sacha, he returned to Guyana where he produced paintings based on the landscape. In 1990, Bowling purchased a loft studio in Dumbo, Brooklyn and split his time between London and New York.

In 1993, Bowling made his first trip to Africa to attend A/Cross Currents: Synthesis in African Painting in Senegal where he won the Pollock-Krasner award. He won the award again in 1998.

Girls in the City, 1991

Benjamin’s Mess (Hot Hands), 2006

Orange Balloon, 1996

In the 1990s, Bowling experimented with composition, occasionally sewing more than one completed canvas together, for example, Girls in the City (1991). He also began to work on smaller canvases than in the past and began to reduce the number of found objects he incorporated into his work. He stopped using acrylic foam completely and smoothed the acrylic gel with a spatula, rather than leaving it to dry in textured lumps. Bowling stated the reason he stapled seven canvases together in Girls in the City was to represent “the way people structure themselves … we live in buildings and express life in opposition to minimalism, enclosure and death.”

In the exhibition, there is at least one painting named after each of his sons, for instance, Benjamin’s Mess (Hot Hands) (2006). Unfortunately, Bowling’s eldest son Dan died in 2001, which prompted him to start using a lot of white in his works as a form of memorial. Despite the grief, Bowling continued to take part in exhibitions, for example, at the Venice Biennale in 2003 and at Tate Britain in 2004. The following year, 2005, Bowling became the first Black artist to be elected to the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

As well as naming paintings after his sons, Bowling titled them after other people he knew or admired. Orange Balloon (1996) was produced for Paul Adams (b.1977), who was both the youngest player in the South African cricket team and the first Black player. The painting itself has little to do with cricket or the cricketer.

Remember Thine Eyes, 2014

Wafting, 2018

Despite needing to sit down due to his age and diminishing mobility, Bowling continues to create art today, employing all the techniques he developed over six decades. Looking at Remember Thine Eyes (2014), it is evident that Bowling still uses his tilted platform, however, because he needs to stand in order to do this, he has only used the one colour (yellow) and possibly only one lot of pouring. The “eyes” have been created by resting two buckets on the wet surface – a technique he accidentally invented in 1981. The title comes from a line in Shakespeare‘s King Lear.

For parts of his artworks, Bowling is assisted by his wife, Rachel Scott who he married in 2013, although had been with since 1977, and his long-term friend Spencer A. Richards. Due to the spontaneity of Bowling’s work, it does not matter if either of them makes mistakes when carrying out Bowling’s instructions.

One of Bowling’s most recent works is Wafting (2018) in which he reverts to using tangible material. The polka dot material, purchased by his grandson Samson in Zambia, has been torn into strips and positioned on top of the canvas. It is not certain whether Richards or Rachel assisted with the fabric, however, Bowling does most of the painting himself, laying canvases on the floor so that he can pour on different colours from a seated position.

Although Frank Bowling’s artworks may not be palatable to everyone, it is a shame his name is not well known. Surely being the first Black man elected to the Royal Academy would have cause for celebration and be an event people would remember? On the other hand, Bowling does not want to be known as a Black painter, he wants his paintings to speak for themselves. After viewing a lifetimes work, it is easy to pick Frank Bowling’s paintings out of a crowd. Beforehand, however, you could be forgiven for expecting him to be a white man; after all, how many Black artists can you name?

By putting emphasis on Bowling’s wish not to be labelled as a Black man, Tate Britain inadvertently draws attention to his geographic and ethnic background. As Bowling said himself, it is something he cannot escape from. Even his artworks continually refer back to his homeland, whether in title or theme.

In the Tate Etc magazine, art critic Matthew Collings mentions that Bowling was disappointed not to see any literature about himself in the lobby of a past exhibition. There were plenty of publications about the other (white) artists who took part, which made it hurt even more. Although racism is less of a problem today, the majority of Bowling’s career as been plagued with adversity.

Some people will love his paintings and others will not understand them, however, regardless of this, Frank Bowling has received what he deserves: a retrospective of his life and career. With the exhibition virtually on his doorstep, Bowling can see his work being appreciated and enjoyed by different generations and know that it is not his skin colour they are interested in but the paintings on display. Finally, he has achieved what he has always wanted.

The exhibition Frank Bowling closes soon on 26th August. Tickets are £13, however, members of the gallery can view for free.

My blogs are now available to listen to as podcasts on the following platforms: Anchor, Breaker, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts and Spotify.

If you would like to support my blog, become a Patreon from £5p/m or “buy me a coffee” for £3. Thank You!