For the next few months, visitors to the National Gallery have the opportunity to discover what happened when artists broke with established traditions to create new art movements. After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art spans the decades between 1880 and the First World War. Impressionism had already shaken the art world, encouraging other artists to experiment with new, modern ideas. The exhibition explores Neo-Impressionism, radical non-naturalist styles, avant-garde artists, Fauvism and Cubism with examples from well-known artists.

The exhibition begins with The Sacred Grove (1884/9) by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1891), who Vincent van Gogh dubbed “the master of us all”. The mural-like painting depicts an ancient grove populated by the muses of the arts. Whilst the scene is a nod towards classical art, the simplified forms, flattened areas and limited colour palette are examples of the ways artists of the 19th century broke away with tradition.

The Museum of Fine Arts in Lyon commissioned Puvis to produce a painting for public display, which served both educational and patriotic purposes. Political opinion still divided France between the Republicans and the Royalists, so the gallery hoped for something to unite the two factions and create a new identity for the country. Critics described The Sacred Grove as a Utopia, and whilst some disliked the limited colours, it gave the painting a dream-like quality.

Puvis included the nine Greek muses and a few nymphs and angels, which makes it difficult for some viewers to determine the figures’ identities. It is generally agreed that Polyhymnia of Rhetoric, Clio of History and Calliope of Epic Poetry are seated in the centre of the painting. Thalia of Comedy and Terpsichore of Dance are in deep discussion towards the left while Euterpe of Music and Erato of Love Songs fly above. Melpomene of Tragedy is recognisable from her dark clothes and melancholic pose, while Urania of Astronomy lies on the riverside.

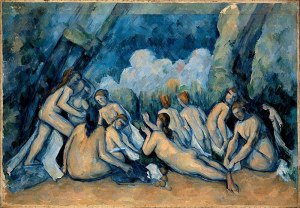

Bathers, painted between 1894 and 1906 by Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), demonstrates Neo-Impressionism, which evolved from Impressionism. Whilst Cezanne drew upon classical pastoral and nude scenes, his execution is rather crude and the bodies distorted. The painting depicts a frieze of eleven naked women relaxing in a woodland glade, which some liken to Titian’s Diana and Actaeon (1559), although Cezanne had no mythological motive.

Cezanne’s artwork is flat and compressed. Although each woman is distinct, their featureless bodies appear as a single mass when viewed from different angles. The scene is predominantly built up from shades of blue, contrasted with touches of orange and brown. Darker blues indicate shadows and trees, which adds perspective to the otherwise flat canvas.

Bathers appeared in the Cezanne memorial exhibition held the year after his death in 1907, which attracted the likes of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. Critics argue whether Cezanne’s crude portrayal of the human body was deliberate or whether he lacked skill. Cezanne once admitted he felt too shy to hire models, so he relied on paintings in galleries for inspiration.

Although opinions were divided over Cezanne’s work, it is evident he influenced many people. Homage to Cézanne (1900) by Maurice Denis (1874-1943) depicts a scene in the shop of the art dealer Ambroise Vollard (1866-1939), who is selling Cezanne’s still-life Fruit Bowl, Glass and Apples. Vollard stands behind the easel, keeping it upright while a crowd of men gather to view the artwork.

The majority of the figures in Homage to Cézanne represent Les Nabis, a group of artists who transitioned from Impressionism to abstract art. They admired Cezanne’s work for its bright, almost unnatural colours. Artists depicted by Denis include Édouard Vuillard, Paul Ranson, Ker-Xavier Roussel and Pierre Bonnard. Denis also inserted a self-portrait and, on the right-hand side, his wife, Marthe. The two men in the foreground are Paul Sérusier and the symbolist painter Odilon Redon. The former is attempting to explain why Les Nabis enjoy Cezanne’s works.

Ironically, Denis’ Homage to Cézanne turns away from the Neo-Impressionist style and Les Nabis by reverting to classicism. Denis produced the painting after a visit to Rome, where he studied classical sculpture and artwork. On his return, Denis argued that classicism was at the core of French cultural tradition. Following a final exhibition in 1900, Les Nabis decided to go their separate ways.

The painting depicted in Homage to Cézanne originally belonged to Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), another artist Les Nabis admired. The exhibition features a handful of works by Gauguin, including Vision After the Sermon (1888), which portrays the Biblical scene of Jacob wrestling with an angel (Genesis 32:22-32). Gauguin initially followed the Impressionist movement but became disillusioned towards the end of the 1880s. Instead, Gauguin preferred a simplified style that reflected his passion for primitive objects and Japanese prints. As a result, Gauguin became the leader of a small group of artists known as Synthesists.

Synthetism was a type of symbolism focusing on artists’ feelings about their subject and the aesthetic considerations of line, colour and form. Painters of this style included Gauguin, Bonnard, Charles Laval, Cuno Amiet and Maurice Denis, the latter of whom summarised synthetism: It is well to remember that a picture before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order.

The influence of Japanese prints is evident in the red background of Vision After the Sermon. Rather than painting a conventional landscape, Gauguin used a flat colour upon which the exaggerated shapes of the figures stand out. Although he used shading on the clothing of the Breton women witnessing the fight between Jacob and the angel, the colours are minimal. The flat tree trunk across the centre of the painting separates the women from the Biblical event, symbolising the women are either having a vision, praying or thinking about the story in the sermon they have just received.

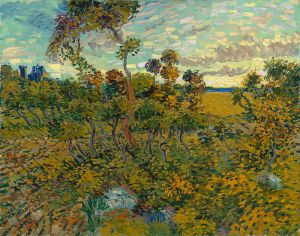

Gauguin spent several years in Breton, evidenced by the women in Vision After the Sermon. Around the same time, he visited his friend, Vincent Van Gogh (1853-90), in Arles. Van Gogh was a troubled soul who spent his later years in southern France before being confined to a mental institution following Gauguin’s visit. Van Gogh did not belong to a particular art movement, but his work inspired many, including the Fauves and the Expressionists.

The authenticity of Sunset at Montmajour (1888) remained questioned for many years after Van Gogh’s death because it was one of the few paintings he did not sign. It depicts scrub land with the ruins of Montmajour Abbey in the background. Van Gogh’s style is distinctive, with bright colours and thick, directional strokes. The authenticity of the painting was confirmed in a letter Van Gogh sent to his brother Theo, in which he described the yellow rays over the bushes as a “shower of gold” and the distant fields as blue and purple.

Working at a similar time to Van Gogh and Gauguin, although in a completely different style, was Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (1834-1917). Degas is predominantly associated with paintings of ballerinas, but he also focused on women in general, such as in Combing the Hair (‘La Coiffure’) (1896). Rather than asking women to pose for him, Degas captured women in secret to create a natural, innocent portrait.

Women combing their hair features in more than one of Degas’ paintings, but this is the only one that uses unnatural colours. Degas limited his palette to fiery orange-reds, a creamy white and black. Apart from a curtain, the background contains no detail, making the ordinary scene feel claustrophobic. The choice of colour suggests the lady had naturally red hair, but it is perhaps also a metaphor for the pain the woman felt while her maid brushed out the matted hair.

Some sections of Combing the Hair are more defined than others. The maid’s clothing contains more detail than the woman in red, who is either pregnant or misshapen. Some claim the picture is unfinished, but others note that Degas suffered from poor sight during his later years, making drawing and painting difficult tasks. His lack of eyesight may explain his choice of colour, which is much stronger than the pastel tones usually associated with Degas.

Two years after Degas’ death, the Fauvist painter Henri Matisse (1869-1954) purchased Combing the Hair, no doubt attracted to the bright, unnatural colour. Unlike Degas, Matisse frequently used models and sitters, as seen in his Portrait of Greta Moll (1908). Moll was a sculptor who attended Matisse’s art school, which opened in 1908. Moll had previously had her portrait taken by Lovis Corinth (1858-1925), which Matisse disliked. Matisse offered to paint a better portrait for 1000 francs, although with no obligation to buy it if Moll prefered Corinth’s attempt.

Three years before painting Greta Moll, the 1905 Salon d’Automne in Paris labelled Matisse and his associates Les Fauves, which meant “the wild beasts”. The term referenced Matisse’s use of bright colours, frenetic brushstrokes and broken lines. By 1908, Matisse wanted to distance himself from the label and understood that a portrait needed to be recognisable, although he still wished to use expressive colours.

Although Moll posed for over three hours, Matisse produced a simplified depiction of the human body. Rather than focusing on detail, Matisse concentrated on the placement of colour, for instance, the warm reddish-brown of Moll’s hair next to the cool blue background.

French artist Georges Seurat (1859-91) also focused on the placement of colour. Seurat devised painting techniques known as chromoluminarism and pointillism, which separated colour and form into tiny dots. The Channel of Gravelines, Grand Fort-Philippe (1890) is the only example of Seurat’s work in the exhibition and dates to the year before his untimely death. Seurat spent a great deal of time on the coast of the Channel, producing landscapes of small port towns, such as Gravelines. Unlike Matisse’s expressive use of colour, Seurat preferred subdued tones.

The Channel of Gravelines, Grand Fort-Philippe is much paler than Seurat’s earlier works, which makes the scene feel deserted. The painting is divided into sky and land, which helps create a sense of depth in an otherwise flat artwork. Only on close inspection are the tiny, pointillist dots visible on the canvas. From a distance, the sky and harbour appear as a wash of colour.

The concentration and colour of the dots produce the outlines and very subtle shading on the boat and houses in Seurat’s landscape. Seurat reserved the darker colours for a painted border, which creates a transition between the painting and the frame. To compliment the shades in the scene, Seurat used deep indigo on the lower frame, reflecting the sky above, and yellow on the upper frame, in reference to the sand below. Several artists adopted Seurat’s technique, including the frame, but the style was short-lived, perhaps due to the painstaking method of producing thousands of tiny dots.

In 1897, a group of Austrian painters formed the Vienna Succession, another short-lived art movement. Before the group split in 1905, it attracted many up-and-coming artists, including Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), known for his use of gold leaf in paintings. Yet, the only painting by Klimt in a British public collection contains no golden features.

Portrait of Hermine Gallia (1904) depicts a wealthy Jewish lady who wanted to establish herself in a predominately Catholic society. Gallia chose Klimt to produce her portrait because he was the most avant-garde and expensive artist of the time. Being able to afford to hire Klimt emphasised Gallia’s wealth and suggested she did not hesitate to embrace modern ideas.

Klimt paid little attention to Gallia’s face, instead concentrating on the pose and fashionable dress. Instead of using gold leaf, as in his seductive portraits of women, Klimt focused on the layers of translucent creamy white chiffon. Many believe Klimt selected or designed the dress specifically for Gallia’s portrait, despite it being a challenging material to paint. Klimt successfully depicted the outfit with long sweeping brushstrokes of thin paint, which allowed the priming of the canvas to show through, creating a translucent effect.

Max Pechstein’s (1881-1955) Portrait of Charlotte Cuhrt (1910) demonstrates another method of portraiture of the early 20th century. Also described as an avant-garde painter like Klimt, Pechstein developed an Expressionist style influenced by Van Gogh and Matisse. He used dynamic brush strokes and highly saturated colours, which became a crucial feature of the artistic group Die Brücke (The Bridge) that he joined in 1906.

The full-length portrait depicts 15-year-old Charlotte Cuhrt in a bright red dress, sitting confidently in an armchair. Her dark hat and flamboyant ring emphasise her status as the daughter of the successful solicitor, Max Cuhrt. The flat background contrasts with the shaded lines of Cuhrt’s clothing, making her appear three-dimensional in a two-dimensional world.

The shape of the canvas fit an altar-like frame, which added to the decorative scheme of Max Cuhrt’s apartment. The architect, Bruno Schneidereit, described the flat as a Gesamtkunstwerk (a total work of art) because every aspect of architecture, furniture and decoration coexisted in aesthetic harmony. Pechstein assisted Schneidereit with the design so that he would understand how his portrait of Charlotte would complete the room.

The final room of the exhibition introduced artists such as André Derain (1880-1954), Georges Braque (1882-1963), Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), who led the way forward in modern art. Before the World Wars, Braque and Picasso established Cubism, which offered an alternative way of portraying the world through fragmented shapes. Mondrian also embraced Cubism but went on to develop abstract art and De Stijl. As modern art became accepted, artists felt free to experiment with different styles and rarely stuck to one movement throughout their career. This is evident in Picasso’s work, which entered a Surrealist phase after the Second World War.

It is impossible to define modern art because there are so many branches, as shown in the After Impressionism exhibition. To say that modern art is everything that came after Impressionism does not enlighten anyone. The National Gallery attempts to chronologically reveal the progression of art, but it quickly becomes evident that there is no linear timeline. Styles came and went and inspired new methods, while some artists, for instance, Matisse, briefly stepped backwards to produce portraits for specific clients.

The National Gallery recommends allowing an hour to visit the After Impressionism exhibition. Some visitors may prefer to stay longer or return another day because there is so much to take in. Modern art does not appeal to everyone, but the curators have enabled visitors to appreciate why styles changed and what inspired the artists involved.

After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art is open until 13th August 2013. Standard admission costs between £24 and £26, although concessions are available. Members of the National Gallery can visit the exhibition for free.

My blogs are now available to listen to as podcasts on the following platforms: Anchor, Breaker, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts and Spotify.

If you would like to support my blog, become a Patreon from £5p/m or “buy me a coffee” for £3. Thank You!

A final note –

A final note –