Until 22nd August 2021, the British Museum is finally hosting its Thomas Becket: murder and the making of a saint exhibition, which celebrates the 850th anniversary of Becket’s brutal murder. Having been postponed due to Covid-19, visitors can now discover the murder that shook the Middle Ages and learn about the life, death and legacy of Thomas Becket. The exhibition features objects from the British Museum’s collection and those on loan from Canterbury Cathedral and other locations around Europe and the United Kingdom. Each object, whether an illuminated manuscript, item of jewellery or a sacred reliquary, helps to tell the story of Becket’s journey from a merchant’s son to an archbishop, to a martyr and a saint.

Thomas Becket was born in Cheapside, London in December 1120 to Gilbert and Matilda. Both parents were of Norman descent and may have named their son after St Thomas the Apostle, whose feast day falls on 21st December. Gilbert Becket was a small landowner who gained his wealth as a merchant in textiles. At the age of 10, Becket attended Merton Priory in the southwest of London. He later attended a grammar school in the city where he studied grammar, logic, and rhetoric. At around 18 years old, his parents sent Becket to Paris, where his education expanded to include the Liberal Arts, such as arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy.

After three years, Becket returned to England, where his father found him a position as clerk for a family friend, Osbert Huitdeniers. Shortly after this, Becket began working for Theobald of Bec (1090-1161), the Archbishop of Canterbury. At this time, Canterbury Cathedral was a place of learning, and Becket received training in diplomacy. Theobald entrusted his clerk to travel on several important missions to Rome. He also sent Becket to Bologna, Italy, and Auxerre, France, to study canon law. Following this, Theobald named Becket the Archdeacon of Canterbury and nominated him for the vacant post of Lord Chancellor.

Thomas Becket was appointed as Lord Chancellor in January 1155. He became a good friend of King Henry II (1133-89), who trusted Becket to issue documents in his name. Becket had access to Henry’s royal seal, which depicted the king sitting on a throne, holding a sword and an orb. For his work as Lord Chancellor, Becket earned 5 shillings a week. The king also sent his son Henry (1155-83) to live in Becket’s household. It was customary to foster out royal children into other noble families, so it was a great honour for Becket.

Following Theobald’s death in 1161, Henry II nominated Becket for the position of Archbishop of Canterbury. This was a strange choice because Becket had no religious education and lived a comparatively secular lifestyle. Nonetheless, a royal council of bishops and noblemen agreed to Becket’s election. On 2nd June 1162, Becket was ordained a priest, and the following day, consecrated as archbishop by Henry of Blois, the Bishop of Winchester (1096-1171).

It soon appeared Henry had an ulterior motive for selecting Becket as the new Archbishop of Canterbury. He wished Becket to continue to hold the position of Lord Chancellor and put the royal government first, rather than the church. This would place the church under Henry’s power, but his plan failed, and Becket renounced the chancellorship, which Henry saw as a form of betrayal. Despite his secular background, Becket transformed into an ascetic and started living a simple life devoted to humility, compassion, meditation, patience and prayer. Becket also started to oppose Henry’s decisions in court, which created significant tension between them.

The rift between Henry and Becket continued to grow throughout the two years following Becket’s archbishopric appointment. Their main arguments focused on the different rights of the secular court and the Church. Henry wished to punish churchmen accused of crimes at court, whereas Becket insisted this infringed upon the rights of the Church. Neither Henry nor Becket gave up their argument, and the issue was never resolved. Becket disagreed with many of Henry’s decisions and refused to endorse and sign documents.

On 8th October 1164, Henry summoned Becket to Northampton Castle to stand trial for allegations of contempt of royal authority and malfeasance in the Chancellor’s office. Despite Becket’s attempts to defend himself, he was convicted of the exaggerated crimes. Angry and fearing for his life, Becket stormed out of the trial and fled to the continent, where he spent six years in exile under the protection of Louis VII of France (1120-80).

Running away did not fully protect Becket from the king. Henry confiscated Becket’s land and wealth in retaliation for leaving the country without his permission. He also forced members of Becket’s family into exile. The king took the opportunity to go against the ways of the Church, knowing that while in exile, Becket could not prevent anything. On 14th June 1170, Henry II had his son Henry crowned as joint monarch at Westminster Abbey. By ancient rights, only the Archbishop of Canterbury could perform coronations, but the king undermined Becket by asking the Archbishop of York and Bishop of London to conduct the ceremony.

Learning of the “Young King’s” coronation, Becket approached Pope Alexander III (1100-81), who had previously forbidden the Archbishop of York from conducting such ceremonies. The Pope permitted Becket to excommunicate the bishops involved. This was a punishment reserved for serious offences.

Becket initiated a fragile truce with Henry II and returned to Canterbury on 2nd December 1170. At this time, Henry was unaware that Becket had excommunicated the bishops involved with young Henry’s coronation but soon learned about the act while at his Christmas court in Normandy. He reportedly flew into a rage and called Becket a traitor and “low-born clerk”. Four of Henry’s knights witnessed this outburst and hatched a plan to arrest Thomas Becket on behalf of the king.

On 29th December 1170, the four knights: Reginald FitzUrse (1145-73), Hugh de Morville (d.1202), Richard Brito and William de Tracy (1133-89), arrived in Canterbury. They found Becket in the cathedral and informed him he had to go to Winchester to account for his actions. Becket refused and proceeded to the main hall for vespers. Meanwhile, the knights went away and returned with their armour and weapons. Seeing this, the monks tried to bar the doors to the cathedral, but Becket allegedly exclaimed, “It is not right to make a fortress out of the house of prayer!”

According to eye-witness reports, the four knights rushed into the cathedral wielding their weapons and shouting, “Where is Thomas Becket, traitor to the King and country?” Standing near the stairs to the crypt, Becket announced, “I am no traitor, and I am ready to die.” The knights attacked, severing a piece of Becket’s skull. “His crown, which was large, separated from his head so that the blood turned white from the brain yet no less did the brain turn red from the blood; it purpled the appearance of the church.” (Gerald of Wales, Expugnatio Hibernica, 1189)

Thomas Becket’s story does not end at his death. The exhibition at the British Museum uses objects to narrate the events in chronological order. Becket’s death occurs only one-third of the way into the narrative, suggesting the Archbishop’s legend had only just begun.

The spilling of Becket’s blood had defiled the sanctity of the cathedral. The monks needed to act quickly to clean up the mess. They placed his body in a marble tomb in the crypt and cleaned up the blood, which they kept in special containers. Due to the number of eye-witnesses, the news of Becket’s death spread quickly, so the monks closed the cathedral to the public to prevent people from entering out of morbid curiosity.

On hearing of Becket’s murder, Henry II was shocked but initially refused to punish his men. This implicated the king of the crime, and rumours soon spread that Henry had ordered his men to kill the Archbishop of Canterbury. Becket’s popularity grew, and Henry feared his people turning against him. The pope also suspected Henry of foul play, so to appease him, Henry performed penance twice in Normandy in 1172. Afterwards, the king travelled to Canterbury to acknowledged his involvement with the crime and asked the monks to punish him accordingly. Henry underwent public humiliation by walking barefoot through the city.

Cult-like worship of Thomas Becket began throughout the country before spreading to the continent. People travelled from far and wide to visit his tomb, which the monks eventually opened to the public. Soon, rumours spread of miracles that happened to those who visited the location of Becket’s remains, which drew thousands more to the cathedral. On 21st February 1173, the Pope officially made Becket a saint and endorsed the growing cult.

Members of the Thomas Becket cult believed the saint’s blood held miracle properties. Becket’s blood-stained clothes were sought by those who believed touching them could cure them of many ailments. The monks also sold Becket’s diluted blood, known as St Thomas Water, to pilgrims in special flasks decorated to reflect the saint’s life. Many unwell people consumed the “water”, who claimed it healed them from their life-threatening illnesses. These flasks have been found as far as the Netherlands, France and Norway, indicating the distance people travelled to visit the saint.

A monk called Benedict, who witnessed Becket’s murder, undertook the task of recording all the miracles that occurred to pilgrims visiting Becket’s tomb. By 1173, he had recorded over 270 stories, and still, people continued to arrive at the cathedral in the hopes of receiving similar treatment. In 1220, Becket’s body was moved to a new shrine in Trinity Chapel, which helped accommodate the influx of visitors. This relocation marked the 50th anniversary of Becket’s death and was celebrated with a ceremony attended by King Henry III (1207-72), the papal legate, the Archbishop of Canterbury Stephen Langton (1150-1228), and large numbers of foreign dignitaries.

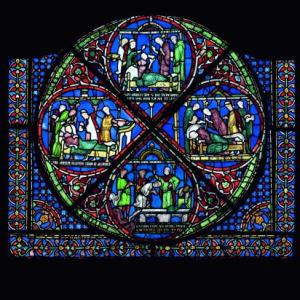

On loan from Canterbury Cathedral is a “miracle window” that reveals several experiences of pilgrims who visited Becket’s shrine. In 1174, the cathedral suffered a devastating fire, which destroyed most of the east side of the building. Over the next fifty years, stonemasons worked laboriously to repair the damage. During this time, they also built a new shrine for Becket’s body. The new chapel was decorated with stone columns and a marble floor. The stained-glass “miracle windows” completed the shrine.

“In the place where Thomas suffered … and where he was buried at last, the palsied are cured, the blind see, the deaf hear, the dumb speak, the lepers are cleansed, the possessed of a devil are freed … I should not have dreamt of writing such words … had not my eyes been witness to the certainty of this.” (John of Salisbury, Becket’s clerk and biographer, 1171)

The six-metre tall windows, twelve in all, only reveal a handful of the miracles following Becket’s death. The window exhibited at the British Museum is the fifth in the series and records people cured of leprosy, dropsy, fevers, paralysis and other illnesses and disabilities. Six panels of the window tell the story of Eilward of Westoning, a peasant accused of theft. He was punished by blinding and castration, but during the night, Becket visited him during a vision. When Eilward awoke, he discovered his eyes and testicles had regrown.

St Thomas’ popularity continued to grow during the next couple of centuries. The pilgrimage to his shrine became as famous as those to Jerusalem, Rome and Santiago de Compostela. Pilgrims arrived from as far north as Iceland and as far south as Italy to visit Becket’s shrine and experience his miracles. The cathedral began selling souvenir badges and other paraphernalia made from lead, resulting in one of the earliest gift shops in the world. The majority of the badges featured images of Becket as the Archbishop of Canterbury or with a sword in his scalp to indicate his murder.

One of these souvenirs is referenced in The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer (1340s-1400), one of the world’s earliest pieces of literature. The book tells the story of an imagined group of pilgrims travelling from London to Canterbury. To pass the time on their journey to the shrine, each character competes to tell the best tale, for which the winner would receive a free meal on their return to the Tabard Inn in London. Chaucer’s characters are an eclectic mix of medieval pilgrims, such as a yeoman, a merchant, a shipman, a knight, a miller and a friar.

Pilgrimages to St Thomas’ shrine continued until the reign of Henry VIII (1491-1547). English kings and their families respected the saint, often visiting the cathedral and commissioning spectacular commemorative items. Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536), did the same, but the king’s attitude towards Thomas Becket changed when he tried to file for a divorce. Pope Clement VII (1478-1534) refused to comply with Henry’s wishes, so he took it upon himself to reject Catholicism and create a new branch of Christianity, the Church of England. In the years following his self-appointment as the Supreme Head of the Church of England, Henry dissolved Catholic convents and monasteries, destroying buildings and their contents in the process.

On 5th September 1538, Henry VIII arrived in Canterbury, where he and his men set about dismantling the shrine of Thomas Becket. They stole the jewels and gold embedded into the tomb, then removed the saint’s bones. Following this act, Henry stripped Becket of his sainthood. Henry VIII’s allies supported his actions and condemned pilgrimages and denounced Becket as a traitor. They removed his name from books, and anything containing references to Becket was destroyed.

Those who opposed the crown continued to revere Thomas Becket. They also respected the former chancellor Thomas More (1478-1535), who shared a similar fate when he opposed the king. No longer able to collect mementos of Thomas Becket, people began treasuring objects connected with Thomas More. Similar acts occurred after the execution of the chancellor Thomas Cromwell (1485-1540) during the reign of Mary I (1516-58).

Devoted Catholics managed to keep Becket’s memory alive by worshipping him in secret during the reigns of Protestant kings and queens. Many items connected to the Archbishop survived due to the number of pilgrims and devotees on the continent. One of the rarest reliquaries to survive is a fragment of Thomas Becket’s skull. The bone rests on a bed of red velvet and is secured in place by a golden thread. It is protected by a silver and glass case upon which is written “Ex cranio St Thomae Cantvariensis”, meaning “from St Thomas of Canterbury’s skull”. It is likely someone smuggled the reliquary out of the country during the Tudor period.

Opinions remain divided as to whether Thomas Becket is a saint and martyr or a traitor and villain. Yet, for the majority of people, Becket is a name confined to school history books. There is no cult following or pilgrimage route, yet kiss marks have been discovered on display cases holding some of the most revered objects. Perhaps Thomas Becket still has a following after all!

Thomas Becket: murder and the making of a saint is open until 22nd August 2021 in The Joseph Hotung Great Court Gallery at the British Museum. Tickets cost £17 for Adults, but Members and under 16s can visit for free.

My blogs are now available to listen to as podcasts on the following platforms: Anchor, Breaker, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts and Spotify.

If you would like to support my blog, become a Patreon from £5p/m or “buy me a coffee” for £3. Thank You!