© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Bump, bump, bump … Is that the sound of a teddy bear being dragged down the stairs? No! It is the sound of a famous bear of very little Brain making his way into the Victoria and Albert Museum. In a unique exhibition, the Best Bear in All the World is celebrated in Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic along with all of his friends. Now in his 90s, Pooh has become a timeless character with universal appeal, however, without the creative partnership between author A. A. Milne and illustrator E. H. Shepard, Pooh’s legacy would not have come to anything at all.

Pooh knew that an Adventure was going to happen …

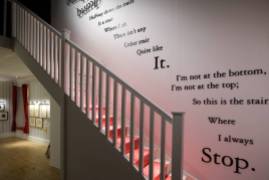

Stepping through the tall double doors, visitors are instantly transported to the fictional setting of Winnie-the-Pooh (1926). From above, Winnie-the-Pooh dangles at the end of a string amongst a barrage of large, pretend, blue balloons – an allusion to the narrative in which Pooh attempts to steal honey from the bees at the top of a tree. Wall illustrations and huge three-dimensional letters warmly welcome everyone Hallo, and thus, the spellbinding adventure begins.

Winnie-the-Pooh first appeared in a book titled When We Were Very Young in 1924. It contains a selection of poems aimed at young children by the author Alan Alexander Milne (1882-1956). It was also the first instance that Milne and E.H. Shepard collaborated together. The pair had met through the British satirical magazine Punch, which Milne was the assistant editor.

Previous to his child-oriented books, Milne had successfully written humorous verse, social satires, fairytales and plays, however, Pooh was destined to quickly overshadow these works. Likewise, Ernest Howard Shepard (1879-1976) had also achieved a lot before the advent of Pooh. The Punch contributor was already well-known for his pen and ink drawings, including the anthropomorphic illustrations of Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows (1908).

The Trinity College, Cambridge graduate, Milne, first experimented with juvenile stories after the birth of his only child Christopher Robin Milne in 1920. The name Christopher Robin has become synonymous with Winnie-the-Pooh and other characters, such as Eeyore and Piglet, but what some people may not realise is that the character was based on the author’s son. By observing Christopher playing in Ashdown Forest, Sussex, near the family’s weekend retreat, Milne concocted ideas for the adventures the fictionalised boy would go on with his favourite zoomorphic toys.

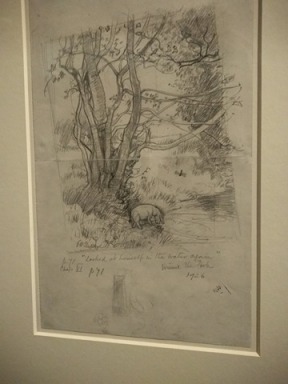

In order to produce the illustrations that would soon be greatly adored throughout the world, Shepard was invited to spend time studying and drawing Christopher’s toys. Sketch after sketch was produced – some of which are on display – until the perfect versions of the characters had been attained; thus, Pooh, Piglet, Eeyore, Tigger, Owl, Rabbit, Kanga, and Roo were born.

A map of the Hundred-Acre Wood

Shepard also spent time in Ashdown Forest drawing the trees and landscape and inventing homes for the funny creatures. The illustrator put in a considerable amount of effort to produce a clever and detailed map of Pooh’s home, The Hundred Akre Wood [sic], which helped to create a consistency throughout the illustrations in Winnie-the-Pooh and its sequel The House at Pooh Corner (1928).

What made Winnie-the-Pooh successful and cause A. A. Milne, to be regarded as the “laureate of the nursery”? Milne’s writing follows the first, although unofficial, rule of children’s fiction: get rid of the parents, then we can begin. Being the only human character, it is likely that children mostly relate to Christopher Robin, an adventurous boy who is usually much cleverer than his silly old bear. However, Milne has given human traits to all the toys/animals.

By using a mixture of thick and thin pen nibs, Shepard subtly conveyed the facial expressions and personalities of each character. Pooh is often striking a pose of mild bewilderment for he is a “Bear of Very Little Brain, and Long Words Bother Me.” Likewise, Piglet often sports a look of surprise at all he encounters.

Milne also gives his characters minor vices, proving that even fictional beings are not completely perfect. The rotund Pooh is a strong example of gluttony with his penchant for honey. As the cupboards in Pooh’s house midway through the exhibition reveal, he can get through ten jars of honey in four days. Bother!

Eeyore is full of self-pity and has since been diagnosed with depression by older readers, whereas, Tigger, the hyperactive tiger, is the vainest of the bunch, falsely believing that there is nothing that Tiggers cannot do – a claim that is disproven time and again. The names of these characters have become adjectives used in everyday life. Melancholy folk are often regarded as Eeyorish, and the sanguine, Tiggerish.

Other vices that appear are idleness (“What I like doing best is Nothing“), evasiveness, self-preservation, and suspiciousness. Being small and defenceless, Piglet is prone to the latter. He has many fears that he bravely faces in quite a few of the stories.

Rabbit, Owl, Kanga, and Roo are secondary characters but each has their own flaws, although, of course, they have virtues, too. Rabbit’s personality is not dissimilar to the stereotypical old man. He is usually portrayed as irritable and has little time for the other toys.

“Hallo, Rabbit,” he said, “is that you?”

“Let’s pretend it isn’t,” said Rabbit, “and see what happens.”

Owl is considered by the others to be wise and is often sought out for advice. Readers will instantly pick up on the inaccuracies of Owl’s intelligence and chuckle as Pooh and friends innocently believe his every word. “Owl hasn’t exactly got a Brain, but he knows Things.”

Kanga is the “mum-friend” of the group and always looks after everyone, including her excitable child, Roo. Whilst Rabbit is making plans and Tigger is causing hullabaloo, Kanga tries to keep everyone in check, although some may accuse her of spoiling all the fun.

Yet, it is not only a good set of characters that make a book an international sensation; the storyline has to attract the minds of its target audience, too. The overall theme is childhood innocence, which would both resonate with youngsters and amuse the adults doing the reading. Each story has its own issue from mishap and misunderstanding, and friendship and falling out, to problem-solving, and learning to read, count or write. In their own special way, each adventure in Winnie-the-Pooh and The House at Pooh Corner is as educative as it is entertaining.

As for the written storyline, Milne simplifies the language for the benefit of children, even going as far as to invent words that youngsters may use instead of correct terms and phrases. Many of these are words Pooh has misheard Christopher Robin pronounce and some are spelt phonetically rather than accurately, for example, Hallo, and Hunny.

The animals’ ability to spell is atrocious, as emphasised in both the text and the illustrations. Wol and Eor replace Owl and Eeyore, and letters are often switched around in the simplest of words. Fortunately, the intelligent reader can determine what these words are meant to say. Milne spices up the text even more by including random capitalisation of nouns. This adds to the child-like narrative and alludes to the characters learning the correct way to read and write.

Poetry is a common feature in the Pooh stories, which adds further hilarity to the story. On his walks around the Hundred Acre Wood, Pooh hums to himself “umty-tiddly, umty-too,” and makes up songs about nature, friendship, and the world around him. The majority of these are nonsense rhymes due to the fact that Pooh thinks Good Thoughts to himself about Nothing … However, the poems rhyme and have since been added to music by Harold Fraser-Simson (1872-1944), a neighbour of the Milne family in Chelsea. Now everyone can sing Tiddle-um-tum and tra-la-la.

Unfortunately, Milne’s style of prose did not sit well with everyone in the 1920s and 30s. Despite its growing success, Constant Reader, a.k.a Dorothy Parker (1893-1967) claimed in The New Yorker that the word hummy “marks the first place in The House at Pooh Corner at which Tonstant Weader fwowed up.”

The books’ harshest critic, however, was the real Christopher Robin, who purportedly hated the stories. Despite this, his restoration and renaming of Posingford Bridge, now Pooh Sticks Bridge, suggest he may not have been as averse as the media claims. A cardboard replica of the bridge is included in the exhibition for visitors to cross over, whilst pretending to play Pooh Sticks over an animated, digital river.

It is clear from the family photographs displayed in a nursery setting that Milne loved his son very much, and it is unlikely that he would have wished to upset Christopher by borrowing his name and toys for his literature. Pictured sitting on his father’s knee, and in another, with his mother Daphne, Christopher Robin poses for black and white photographs. He is also pictured in the woods with his toy bear who was about to become famous throughout the world.

Teddy bear, manufactured by Margarete Steiff, 1906 – 10. Museum no. MISC.10-1970. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Examples of bears that were similar to Christopher Robin’s are on display, including ones made specifically for the recent film Goodbye Christopher Robin (2017). Another bear, similar to the one belonging to E. H. Shepard’s son, sits beside Christopher’s. The reason for this is Shepard used both bears as visual references when developing the iconic illustrations.

Throughout the writing and publishing process, Milne and Shepard were in close contact, with letters being sent back and forth containing new ideas and suggestions. A few of these have been acquired by the V&A, and visitors are invited to read them if they are able to decipher the tiny, almost illegible, writing.

By working together on Winnie-the-Pooh, the original book became one of the first of its kind in which text and illustration worked together. Traditionally, an illustrator was given a completed manuscript to draw scenes for, which would then be placed in strategically positioned sections of the page. What Milne and Shepard achieved were instances where text and illustration combined to make a complete image. In some instances, Milne refers to the pictures or refrains from mentioning the character’s name because the reader can already see to whom is being referred.

The entirety of the exhibition is made up of temporary walls containing enlarged versions of E. H. Shepard’s illustrations. By making them life-size, the museum has created a playground for children where they can walk through tiny doors, ring bells, open cupboards, climb into Piglet’s house and slide back out, sit at a table in a pretend forest and draw their own trees, and so on.

Whilst the children are having a fun, enjoyable experience, the adults are able to study some of the original manuscripts and illustrations. Over 270 drawings, letters, proofs, and photographs make up this extensive collection. The museum has gone even further to explain the techniques Shepard used to create atmospheric scenes, suspended animation, and the all-important human traits. Artists and illustrators may benefit from taking note of the use of lines and shading, and the clever trick of adding white gouache to create a snowy effect.

Before the exhibition really gets underway, a corridor fitted with a lengthy glass case reveals the many faces of Winnie-the-Pooh from the 1920s up until the present day. Winnie-the-Pooh had only been on bookshelves for four years when the father of the licensing industry Stephen Slesinger (1901-1953) began designing products featuring the increasingly popular illustrations. The ‘Teddy Toy‘ company founded by B.C. Hope and Abe Simmonds made some of the earliest Pooh merchandise, including a golden teddy bear.

The commodification of Pooh escalated further in 1966 when Disney produced its first animated film based on Milne’s stories. For this, art workers simplified the black and white drawings to fit their house style and gave Pooh the red t-shirt he is often seen wearing today. Alongside the film came a whole host of paraphernalia with new ideas being developed every year.

The books themselves have been translated into over 30 languages, including Latin. Not only that, new books have been published with simplified stories containing updated illustrations. Pooh has also been the face of cookery books, political satire, and a whole host of other things. Examples of these are situated in the primary section of the exhibition.

The final section of the exhibition reveals how E. H. Shepard’s black and white illustrations became the coloured versions that many children are familiar with today. Disney had already brought the stories into the colour world and determined the shades of each character, specifically Pooh and his redshirt. When the publisher Frank Herrmann (b1945) decided in 1970 to add colour to the originals, Shepard was already in his 90s and rapidly losing his sight. Nevertheless, with the aid of enlarged copies of his drawings, he developed coloured versions, however, due to the popularity of the Disney Winnie-the-Pooh, had to conform to the colours the public had grown to expect.

The coloured versions are bold and bright like many illustrations in the 1960s and 70s. Unfortunately, this removed the delicacy of the original hand-drawn lines, making them less detailed and gentle. This may have been the norm for illustrations of that era, however, in hindsight, the originals were already perfect.

The coloured versions are bold and bright like many illustrations in the 1960s and 70s. Unfortunately, this removed the delicacy of the original hand-drawn lines, making them less detailed and gentle. This may have been the norm for illustrations of that era, however, in hindsight, the originals were already perfect.

Here, the exhibition comes to an end. After a superb adventure through the minds of both the author and illustrator, visitors are much more informed about the silly old bear and his origins. Winnie-the-Pooh is much more than a story for children, he has found a permanent home in the world and it is difficult to imagine a life without him.

The Victoria and Albert Museum has excelled in its curation of Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic. Not only is it a grand display of illustration, it is like entering a different world. It is hard to believe that the same gallery hosted the Pink Floyd exhibition mere months ago.

Suitable for anyone between the ages of two and 102, Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic is worth the visit. It brings fresh insight into children’s literature and will hopefully ignite a passion for reading within the younger generation.

So they went off together. But wherever they go, and whatever happens to them on the way, in that enchanted place on top of the hill, a little boy and his bear will always be playing.