Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), one of the pioneers of abstract art, is known for his use of primary colours and simple geometric shapes. Whilst his work is highly recognisable, his philosophy that art should reflect the spiritual world is less known. Until 3rd September 2023, Tate Modern is exploring Mondrian’s life, work and philosophies alongside Hilma af Klint (1862-1944), a lesser-known female abstract artist.

Pieter Cornelis Mondriaan was born in Amersfoort, the Netherlands on 7th March 1872 to strict Protestant parents. His father, of the same name, worked as a head teacher but was also a qualified drawing teacher. Having been introduced to art at a young age, Mondrian entered the Academy for Fine Art in Amsterdam after qualifying as a primary school teacher. For some time, he managed to combine his career in education with his love of art, producing naturalistic and Impressionistic paintings in his spare time.

Most of Mondrian’s early works are landscapes featuring pastoral scenes. Influenced by his home country, Mondrian frequently painted windmills, rivers, fields and trees. Whilst these were representational works, Mondrian experimented with the many art movements of the late 19th century, including Impressionism, pointillism and Fauvism. By 1893, he had enough work to display at his first exhibition.

Mondrian’s early works begin to show a degree of abstraction as he started to experiment with different colour palettes, for instance, red, yellow and blue. The trees and other features gradually became less distinct, such as Gray Tree (1911), which Mondrian produced while staying in Paris. While living in France between 1911 and 1914, Mondrian changed his surname from Mondriaan to Mondrian and took inspiration from the Cubist artists Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Georges Braque (1882-1963). Although Gray Tree contains a measure of representation, the branches are more angular and geometric than in his previous work.

In 1908, Mondrian developed an interest in Helena Petrovna Blavatsky’s (1831-91) Theosophical Society, which believed it was possible to gain a spiritual knowledge of nature. Through his work, Mondrian determined to seek this knowledge. Mondrian and other artists, such as Hilma af Klint, sought to present spiritual concepts visually using abstract techniques and colours. Joining the Dutch branch of the Theosophical Society in 1909 had a greater impact on Mondrian’s aesthetic than the myriad of competing art movements.

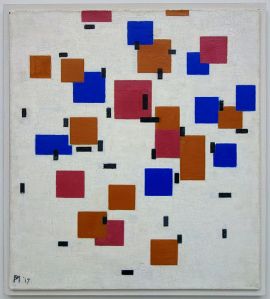

While Mondrian was visiting his home country in 1914, the First World War began, forcing him to remain in the Netherlands for the next four years. During this time, he resided in the artists’ colony in Laren, where he met Bart van der Leck (1876-1958) and Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931). Although Mondrian had experimented with primary colours in the past, Van der Leck’s exclusive use of the colours red, blue and yellow had a profound impact on Mondrian’s artwork. Van Doesburg, whilst using a wider range of colours, encouraged Mondrian to continue developing his Cubist style.

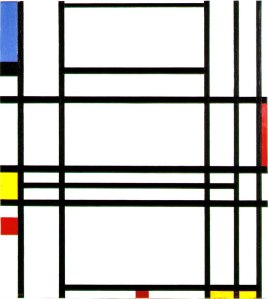

Gradually, Mondrian’s work became less pictorial and moved away from Cubism. Together with Van Doesburg, Mondrian founded De Stijl (“The Style”), also known as Neoplasticism, in 1917, which advocated pure abstraction. Whilst Cubism is an abstract movement, De Stijl reduced visual compositions further to vertical and horizontal lines and shapes, using only black, white and primary colours.

Between 1917 and 1918, Mondrian published an essay called Neo-Plasticism in Pictorial Art in instalments in the new movement’s magazine, also called De Stijl. Mondrian believed traditional representation art only focused on the external world, whereas geometric abstraction created a sense of balance and harmony to emphasise the internal qualities of the universe. Mondrian also maintained that the fundamental principles of the universe could be demonstrated in grid-like compositions.

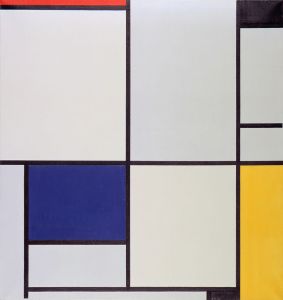

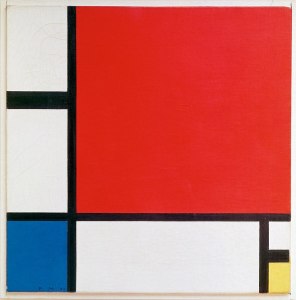

After the First World War, Mondrian returned to Paris, where he remained for two decades. Here, he fully embraced “pure abstract art” and produced some of his most iconic artworks. Mondrian began by painting grid-like compositions consisting of thin black lines forming rectangles, which he filled with blue, red, yellow, grey or white paint. Over time, the black lines increased in thickness, and the number of geometric shapes reduced.

Although digital and photographic versions of Mondrian’s paintings appear flat, that is not the reality. The black lines are the flattest parts of the compositions, whereas the coloured sections are built up from many layers of paint. Close examination reveals Mondrian only moved the paintbrush in one direction when applying red, blue or yellow, but the white sections have brush strokes running in several different directions.

“Holland has produced three great painters who, though a logical expression of their own country, rose above it through the vigour of their personality – the first was Rembrandt, the second was Van Gogh, and the third is Mondrian.” So said Katherine Dreier (1877-1952), a founder of New York City’s Society of Independent Artists, after visiting Mondrian’s studio in Paris. Dreier purchased one of Mondrian’s paintings and exhibited it in the United States at the end of the 1920s.

During the 1930s, Mondrian significantly reduced the amount of colour in his compositions. He began to focus on the impact of lines, frequently doubling them up to create a new dynamism. These paintings are visually busier than his earlier grid-style canvases.

Due to the rise of Fascism, Mondrian left France for London in 1938, where he resided for two years. After Paris fell to the Nazis in 1940, Mondrian left Europe altogether, settling in Manhattan, New York. Mondrian continued to produce grid-like compositions, which, despite their simplicity, took hours to execute.

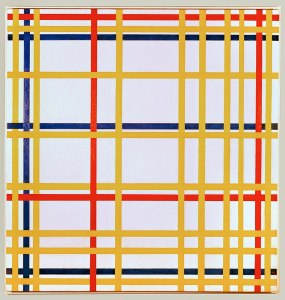

Moving to America brought about a significant change in Mondrian’s work. Rather than using black lines and blocks of colour, Mondrian began using red, yellow and blue lines instead. New York City (1942) is one example of Mondrian’s new style. The lines towards the top of the painting are denser than at the bottom, which some critics suggest represents the sky.

Using strips of tape, Mondrian experimented with the position of the lines before painting directly on the canvas. The technique is evident in the unfinished painting New York City I, which has some similarities to the completed New York City. The unfinished work hangs in the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf, Germany. Last year, an unearthed photograph of the painting in Mondrian’s studio proved the artwork had been hung upside down in the gallery.

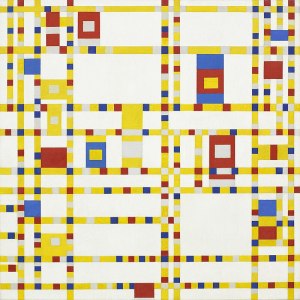

The grid-like cityscape in Manhattan inspired many of Mondrian’s artworks during the years he spent in America. He also took inspiration from the people in the city, particularly the jazz scene. Broadway Boogie Woogie (1943) incorporates rigid architecture and jazz tones by dividing the composition into more squares than previous works. Mondrian replaced solid lines with small adjoining rectangles of colour. Some critics suggest Mondrian captured the neon lights that dotted the city during the night.

“Mondrian’s life and his affection for music are mirrored in the painting [and that it is] a testimony of the influence which New York had on Mondrian.” So said Jürgen Stoye about the unfinished artwork Victory Boogie Woogie. Whilst some lines and shapes are complete, pieces of coloured paper indicate where Mondrian intended to paint. Stoye believed the music scene of New York began to influence Mondrian more than the grid-like architecture. Mondrian’s decision to rotate the canvas by 45 degrees may support this theory.

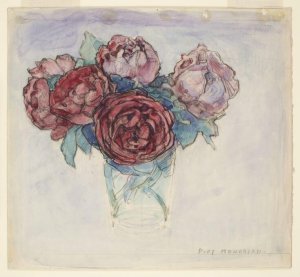

Despite Mondrian’s reputation for abstract art, he had a secret passion for painting flowers. He began producing floral images early in his career before branching out into Cubism and De Stijl, yet, Roses in a Vase (1938-1940) proves Mondrian continued to work on these subjects in private. Mondrian claimed to his close friends that he only painted flowers for commercial reasons, but the truth of this claim remains uncertain.

Piet Mondrian passed away on 1st February 1944 from pneumonia at the age of 71. Nearly 200 people attended his memorial service in Manhattan, including the artists Marc Chagall (1887-1985) and Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968). Mondrian left his estate, including the copyright to all his works, to his friend Henry Holtzman (1912-87), who had arranged Mondrian’s passage from London to New York in 1940. When Holtzman passed away in 1987, his children established the Mondrian/Holtzman trust to look after the paintings until the copyrights expired in 2015.

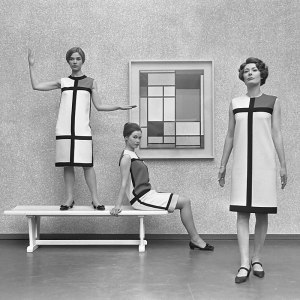

As an artist, Mondrian has inspired and continues to inspire many people. Art critic Robert Hughes (1938-2012) described Mondrian as “one of the supreme artists of the 20th century” who “believed that the conditions of human life could be changed by making pictures”. With such a distinctive and recognisable style, Mondrian’s work was quickly appropriated by other artists, particularly fashion designers. Before his death, Hermès designed a range of bags based on Mondrian’s latest paintings. Three decades later, Yves Saint Laurent released the 1965 Mondrian collection, featuring Mondrian’s iconic black lines and blocks of primary colours.

In 2008, the athletic footwear company Nike released a pair of trainers based on Mondrian’s De Stijl paintings. Since the copyright on Mondrian’s work expired in 2015, the amount of Mondrian-inspired fashion has risen considerably. A quick search on Google finds dresses and shirts on sale at Shein, Etsy, and ASOS. Dutch companies, such as the Miffy Shop, based on illustrations by Dick Bruna (1927-2017), have also embraced Mondrian’s style.

Modern art is subjective and open to interpretation. Some people may not appreciate Mondrian’s unique style or understand his work, but it does not diminish the fact that it has had a huge impact on the art world. Designers have put Mondrian’s pleasing patterns to good use, incorporating them into fashion and graphic design. Yet, beneath the layers of paint is an artist attempting to create a sense of balance and harmony in a world full of war, hate and fear.

To view some of Piet Mondrian’s paintings and notebooks in conjunction with Hilma af Klint, visit the Forms of Life exhibition at Tate Britain. Tickets are available until 3rd September 2023 and cost £20. Some concessions are available.

If you would like to support my blog, become a Patreon from £5p/m or “buy me a coffee” for £3. Thank You!