Quixotism is a term to describe the impractical ideas or an extravagant chivalrous action made by an impulsive person. The term comes from the word Quixote, which was invented by the Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes for the titular hero of his 1605 novel Don Quixote. By the mid 17th century, the term was being widely used to describe someone who could not distinguish between reality and imagination, just like Cervantes’ famous character.

Don Quixote is considered by most to be the world’s first modern novel and Miguel de Cervantes is still regarded as the greatest Spanish writer. Searching through online exhibitions from Spanish museums via Google Arts & Culture, Cervantes crops up again and again, suggesting he is respected as a national hero. Yet, his life remains a bit of an enigma. It is generally believed he spent the majority of his life in poverty, however, there are some disputed claims in his biographies that sound rather quixotic…

- By Attributed to Juan Martínez de Jáuregui y Aguilar

- Portrait of an Unknown Gentleman – El Greco (1603-07)

It is not certain what Cervantes looked like, or even if that was his name. A portrait, attributed to Juan Martínez de Jáuregui y Aguilar (1583-1641), is said to be of the author, however, the signature and title were added to the painting centuries later. El Greco’s (1541-1614) Portrait of an Unknown Gentleman is rumoured to be a painting of Cervantes, however, there is no tangible evidence.

As for his name, he often signed his name Cerbantes, although his publishers always used Cervantes. He also had around eleven different signatures and, later in life, began to use the name Saavedra, which may have been the name of a distant relative or the Spanish version of an Arabic nickname he was given, meaning “one-hand”.

Miguel de Cervantes was born around 29th September 1547 in Alcalá de Henares, a Spanish city 22 miles from Madrid. His father, Rodrigo de Cervantes, was a barber-surgeon (someone who could use the same blade to shave your head or chop off your leg) from Córdoba, Andalusia. Although Cervantes’ paternal grandfather, Juan de Cervantes, was a successful lawyer, Rodrigo was frequently in debt and struggled to find work.

Cervantes’ mother was Leonor de Cortinas (c. 1520–1593) who came from Arganda del Rey but moved to Córdoba after marrying Rodrigo. Records suggest she was a resourceful woman, capable of looking after her children while Rodrigo was frequently in debtor’s prison. Records also reveal Leonor was able to read and write, therefore, she may have been responsible for educating her seven children when they were young: Andrés (b. 1543), Andrea (b. 1544), Luisa (b. 1546), Miguel (b. 1547), Rodrigo (b. 1550), Magdalena (b. 1554) and Juan (b.1556c).

By 1564, the family were living in Seville where Rodrigo had secured rented accommodation from his brother Andres. Although there is no written record, Cervantes and his siblings likely attended the local Jesuit college, however, in 1566, the family were forced to move to Madrid because Rodrigo was, once again, in debt.

- Bust of Cervantes erected in 1905, Burgos, Spain

- Statue of Miguel de Cervantes at the harbour of Naupactus (Lepanto), Greece

An arrest warrant dated 15th September 1569 reveals Miguel de Cervantes was charged with wounding a man named Antonio de Sigura in a duel. Who this man was is unknown, however, the incident is likely the reason Cervantes soon left Madrid and travelled abroad to Rome.

In Rome, Cervantes found a position in the home of an Italian bishop, Giulio Acquaviva of Aragon (1546-74), who had just been made Cardinal-Deacon of San Teodoro by Pope Pius V (1504-72) on 17th May 1570. What Cervantes did during this time is, of course, unknown, however, he cannot have been there that long before the Ottoman–Venetian War began (1570-73).

The Marquess of Santa Cruz

The Ottoman–Venetian War, also known as the War of Cyprus, was waged between the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Venice, the latter of whom was supported by Spain and several Italian states. When the war began, Cervantes, perhaps hoping it would redeem him from his earlier arrest, travelled to Naples to enlist. Don Álvaro de Sande (1489-1573), a Spanish military leader and friend of the family, found Cervantes a position under the Spanish admiral Álvaro de Bazán, 1st Marquess of Santa Cruz (1526-88).

Cervantes’ brother, Rodrigo, also enlisted in Naples and in September 1571, the siblings sailed on the Marquesa, which was one of the ships in the fleet of Don John of Austria (1547-78), the illegitimate son of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500-58) and half-brother of King Philip II of Spain (1527-98). Cervantes’ written account of life aboard the Marquesa reveals he was put in charge of a 12-man skiff who were forced to fight despite suffering from malaria.

The Battle of Lepanto by Juan Luna (1887)

On 7th October 1571, the fleet defeated the Ottoman Empire at the Battle of Lepanto, however, the Marquesa suffered many fatalities. A total of 40 men were killed and a further 120 wounded, including Cervantes who received two blows in the chest and one in his left arm, which rendered it useless.

Cervantes wrote a poetic account of his experiences in battle, which was published in 1614 under the Spanish title Viaje del Parnaso (Journey to Parnassus). He declared he had “lost the movement of the left hand for the glory of the right”, but needed to spend six months in hospital in Messina, Sicily, to recover from the chest wounds.

In July 1572, Cervantes returned to service, however, records reveal it was still several months before his chest wounds had fully healed. During this time, Cervantes was mostly stationed in Naples, however, he took part in expeditions to Corfu and Navarino in Greece. The following year, he took part in the occupation of Tunis and La Goulette in Tunisia, which was, unfortunately, recaptured by the Ottoman Empire in 1574, thus giving them overall victory. Despite Spain’s loss, Cervantes was given letters of commendation from the Duke of Sessa, Gonzalo II Fernández de Córdoba (1520-78).

In September 1575, Cervantes and Rodrigo boarded the galley Sol to make their homeward journey to Barcelona. Unfortunately, the galley never got there. As they approached the city, the slender ship was attacked and captured by Ottoman corsairs, also known as Barbary Pirates, who took everyone on board to Algiers as their prisoners. The pirates sold many of their captives as slaves and kept the rest as hostages. Cervantes and his brother fell into the latter category and a ransom letter was sent home to their family.

Kılıç Ali Paşa (1837)

The brothers’ family could not afford to pay the ransom for them both, so only Rodrigo was able to return home. Forced to stay, Cervantes may have been used as a slave, however, there is no proper evidence of what his life was like at this time. One suggestion is Cervantes was one of the construction workers of Kılıç Ali Pasha Complex, a mosque in Istanbul built between 1578 and 1580. If this is true, then Cervantes and some of the other prisoners must have been moved to Turkey. The mosque was named after the Grand Admiral of the Ottoman fleet, who had many names, including Kılıç Ali Pasha. Born Giovanni Dionigi Galeni (1519-1587), he is mostly known in history books as Occhiali, however, he did feature in Cervantes’ Don Quixote under the name Uchali.

If Cervantes did work on the construction, he would have likely struggled without the use of his left arm. It may have been here that he was given the nickname “one-hand”, which may have led him to adopt the Spanish equivalent, Saavedra, as his surname.

Cervantes was in captivity for five years during which he attempted to escape at least four times. Throughout this time his family never raised the required ransom money but, in 1580, Cervantes was fortunate to be “rescued” by the Trinitarians. The Order of the Most Holy Trinity and of the Captives, to give them their full name, was founded by Saint John de Matha (1160-1213) in the 12th century with the express purpose of paying the ransom for Christians held captive by Muslims.

After his rescue, Cervantes returned to Madrid, however, he struggled to find work. His military employers, Don John of Austria and the Duke of Sessa, were both dead, therefore, there was no one suitable to provide Cervantes with a reference. Not much is known about how Cervantes lived between his release and 1584, however, some sources claim he was employed as a spy in North Africa.

By 1584 he was back in Madrid where he had conducted an affair with a married woman called Ana Franca. In November, his illegitimate daughter Isabel was born and, although Cervantes acknowledge paternity, he was then engaged to someone else. After her mother died in 1598, Isabel went to live with Cervantes’ sister, Magdalena.

In December 1584, Cervantes married Catalina de Salazar y Palacios (c.1566-1626) who he had met when visiting the home of a deceased friend in Castile-La Mancha. It is not certain what year Catalina was born, therefore, she could have been anywhere between 15 and 18-years-old on their wedding day. Their wedding documents are the first written record of Cervantes’ use of the double surname Cervantes Saavedra.

It appears Cervantes continued to struggle to find work and even when he was employed, it was not always straightforward. In 1587, he was appointed a governor purchasing agent but soon moved on to be a tax collector instead. Either Cervantes was not good at the job or he was deliberately committing fraud because he was frequently arrested for irregularities in his accounts. Records also show he made several applications for posts in “Spanish America”, however, these were rejected.

At the end of the 16th century, Cervantes was living in Seville but moved to Madrid in 1606. Again, it is not certain what form of employment Cervantes took, however, he was later receiving financial support from Pedro Fernández de Castro y Andrade, better known as the Great Count of Lemos (1576-1622). The Count was a patron of several writers, which suggests Cervantes may have been a full-time author.

In 1613, Cervantes joined the Secular Franciscan Order, also known as the Third Order Franciscan, which was formed of male and female Catholics who wanted to follow the Gospels in the manner of Francis of Assisi (1181-1226). The order was not bound by any religious vows but was a typical way for a Catholic to gain spiritual merit towards the end of their life.

Three years later on 16th April 1616, Cervantes died from what is believed to have been diabetes. Reports of his death record he suffered from excessive thirst, which is a common symptom of the disorder, which at that time was untreatable. As stipulated in his will, Cervantes was buried in the Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians in Madrid. No evidence suggests Cervantes attended the Church, however, he felt he owed the Trinitarians for rescuing him from slavery.

As befalls many great authors of the past, Cervantes’ fame came after his death. Supposedly, Cervantes had written around two dozen plays by the end of the 16th century, however, only two survive today: El trato de Argel (The Deal in Algiers) and El cerco de Numancia (The Siege of Numantia). The former was based on his time in captivity, however, it did not earn him much money. Playwrighting was one of his many failed careers.

Cervantes’ first attempt at a novel was published in 1585 under the title La Galatea. Contrasting rural and city folk, the main characters, a rural herdsman called Erastro and a cultured shepherd called Elicio, vied for Galatea’s love. Through their dialogue, the reader learns about the differences between pastoral and urban life. Both men believed the other to have certain advantages and a simpler life, however, they soon learnt this is not the case. Cervantes promised a sequel but never got around to writing it.

La Galatea was not a major success in terms of earnings but attracted the attention of many readers and authors. Cervantes also wrote several short stories, which were collectively published in 1613 and dedicated to the Count of Lemos, who was by then his patron. It is not certain whether La Galatea earned Cervantes a patron or whether it was his second novel, for which he is most remembered.

In 1605, Miguel de Cervantes decided to challenge the ‘vain and empty’ chivalric romance stories that were popular at the time. The result was El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha (The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha), more commonly shortened to Don Quixote. This was actually volume one of the story we know today, however, at the time of publication, Cervantes may not have intended to produce a sequel.

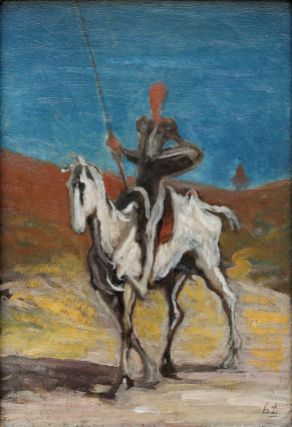

Labelled “the first modern novel”, Don Quixote follows the adventures of Alonso Quixano, who had read so many chivalric romance stories that he lost his mind and decided to become a caballero andante (knight-errant) like the heroes of the tales and serve his country. Having recruited a simple farmer, Sancho Panza, as his squire, Quixano travelled around the country, imagining he was performing his knightly duties.

At the beginning of the story, 50-year-old Quixano was living with his niece and housekeeper in La Mancha. His niece realised her uncle was losing his mind when he, a typically rational man, began to lose touch with reality. Having donned an old suit of armour, there was nothing anyone could do to stop Quixano, who had renamed himself Don Quixote, from setting off on his old horse, Rocinante. Since the heroes of his favourite stories always had a “lady love”, Don Quixote set his heart on his neighbour, Aldonza Lorenzo, whom he renamed Dulcinea del Toboso.

On his journey, Don Quixote met lots of trouble, mostly due to his irrational view of the world. He mistook a brothel for a castle, two friars for enchanters, windmills for giants and a serving girl for a princess. Being slow and ignorant, Sancho Panza did not realise Don Quixote’s monologues and actions were pure fantasy and offered his master his full support throughout the adventure. Eventually, after many mishaps, Don Quixote returned home.

When the book was first published, it was an immediate success. In an attempt to earn money, 400 copies were shipped to the Americas, although, due to shipwrecks, only 70 arrived in Peru. Unfortunately, Cervantes had sold his work to the publishers, therefore, there was no copyright. Pirated copies began to appear across Spain, which deprived Cervantes of financial profit.

In Cervantes’ 1613 book of short stories, he promised his readers a sequel to Don Quixote: “You shall see shortly, the further exploits of Don Quixote and humours of Sancho Panza”. The following year, however, he was preempted by an unofficial sequel to Don Quixote, published under the name Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda. There are many theories about who this pseudonym belonged to, including those who think it was Cervantes stalling for time by faking a scandal. Nonetheless, the writing is poor compared to Cervantes’ and was quickly rejected by the public.

The real sequel was eventually published in 1615, ten years after the first part. Whilst Part One had been farcical, Part Two was more serious and philosophical. Due to his previous antics, Don Quixote was well-known across the country. Still delusional, strangers decided to take advantage of the confused man, resulting in a series of practical jokes. Still devoted to Dulcinea, Don Quixote sent Sancho Panza to find her, however, he returned with three peasant girls and told his master they were Dulcinea and her ladies under an enchantment. A Duke and Duchess led Don Quixote to believe the only way to lift the spell was to receive three thousand three hundred lashes, although Sancho prevented this from happening.

The story begins to end after a battle on the beach in Barcelona, which Don Quixote lost. The agreed prize for the winner was that the other had to obey the will of the conqueror. The victor declared Don Quixote had to refrain from acts of chivalry for a year. Returning home, Don Quixote fell ill, which remarkably restored his sanity. His final act was the penning of his will, in which he stipulated his niece would be disinherited if she married a man who read books of chivalry.

Both parts of Don Quixote have been published together since 1617, the year after Cervantes’ death. The same year, Cervantes’ final work Los Trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda (The Travails of Persiles and Sigismunda), a romance story that he completed three days before he died. It did not, however, receive much praise.

Miguel de Cervantes Memorial by Jo Mora, presented to city on Sept 3, 1916 – Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, California

Don Quixote is Miguel de Cervantes biggest legacy, for which he is known throughout the world. He is celebrated across the ocean in America where a memorial statue sits in San Francisco by Uruguayan sculptor Joseph Jacinto Mora (1876-1947). In Australia, a town near Perth bears Cervantes’ name, as does a municipality in the Philippines and Spain. There are several establishments named after the author, including the worldwide education charity Instituto Cervantes, the Miguel de Cervantes European University (Spain), the Miguel de Cervantes Health Care Centre (Spain) and the Miguel de Cervantes University (Chile).

Nowhere, of course, celebrates Cervantes more than his home country of Spain. Located in the city of Valladolid, Spain, is the Casa de Cervantes, a museum set in the house in which Cervantes was living in 1605. The museum consists of 17th-century furniture, paintings and ceramics relating to the author.

In Madrid, the Museo Casa Natal de Cervantes (Cervantes Birthplace Museum) is situated in what scholars believe was the family home where Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra spent his early years. Each room of the house represents the culture, activity and customs of the 16th and 17th centuries to help visitors envisage the life of Cervantes. The museum also boasts a significant collection of Cervantes’ works and provides activities for children, theatre students and literature students throughout the year. They also celebrate the annual Cervantes Week around 12th October.

Whilst it is the legendary Don Quixote that draws people to these museums, it has to be said that Miguel de Cervantes had an equally interesting life. Despite very few facts being known for certain, his experience in war and his capture by pirates make a fascinating story.

Evidence of Spain’s love of Miguel de Cervantes can be seen on Google Arts and Culture, which features several online exhibitions and articles about the author. Examples include:

Miguel de Cervantes: a life of adventure by Agencia EFE S.A.U.

The Don Quixote Route by Agencia EFE S.A.U.

Miguel de Cervantes: From Life to Myth by Acción Cultural Española (AC/E)

Cervantes, the brilliant author by Archivos Estatales

Cervantes in the World by Agencia EFE S.A.U.

Museo Casa Natal de Cervantes by Museo Casa Natal de Cervantes

The female world in Don Quixote by Instituto Universitario de Investigación

“He who loses wealth loses much; he who loses a friend loses more; but he that loses his courage loses all.”

Miguel de Cervantes

My blogs are now available to listen to as podcasts on the following platforms: Anchor, Breaker, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts and Spotify.

If you would like to support my blog, become a Patreon from £5p/m or “buy me a coffee” for £3. Thank You!