Have you ever looked at a piece of writing and instantly known it was written several decades or even centuries ago? What gives it away? The condition of the paper or parchment is a good indication; if it is stained, torn and fragile, it is unlikely to have been written yesterday. The use of language also hints at its time frame, however, so does the style of handwriting. Compare your handwriting with those in handwritten books in the British Library, British Museum or collections such as the one at the Derbyshire Record Office. Why do we no longer write like our ancestors 800 years ago? What changes occurred to result in the simplified letters of today? Handwriting, as you will discover, has a surprisingly interesting history.

The history of writing dates back further than the invention of paper and pen, however, the history of handwriting in the ways that we are familiar today, date back to around 1100 – at least in Britain. During this early Medieval period, which lasted until approximately 1485, there were very few people who could read and write. Only those with important jobs or children from rich families were taught to read but mostly, the “profession” of writing was left to the specially trained scribes.

Naturally, not many examples of writing exist from the Medieval period of Britain due to damage and loss, however, the samples that have survived tend to be legal documents, such as deeds of ownership. These were written in Latin as most deeds were before 1752. Unlike today where all important documents are signed and dated to avoid legal complications, these documents rarely mentioned the date and historians have only roughly worked out when they were written by the style of handwriting. There were, of course, handwriting styles that were preferred for other languages, for instance, Gothic, Anglo-Saxon and Gaelic. These languages, however, were used in local areas, whereas, Latin could be understood by people in several countries.

Carolingian minuscule alphabet

This Medieval style of handwriting has been named Carolingian minuscule or Caroline minuscule and was developed in c.780 AD by Alcuin of York (735-804), a Benedictine Monk of Corbie Abbey, France. Alcuin had been invited to France by Charlemagne (748-814), who had founded the Carolingian Empire, hence the name of the script.

Alcuin of York and his fellow monks were responsible for writing and copying religious documents, which they did in Carolingian minuscule. Soon, the style of handwriting was being used throughout the Holy Roman Empire for both Christian and Pagan texts. The Vulgate, a 4th century Latin translation of the Bible originally written by Jerome of Stridon (347-420; Saint Jerome) was copied in Carolingian minuscule to make it legible to literate classes across Europe.

Carolingian minuscule was a rounded, uniform style of writing based on the Latin alphabet, which has many similarities to the modern alphabet. It was easy to distinguish between upper and lowercase letters and there were clear spaces between each word. Whilst most of the letters are recognisable today, there were no tittles (dots) above the letters i and j, however, other markings occasionally appeared above certain letters. Whereas in contemporary modern languages these markings would change the pronunciation of the letter, Carolingian scribes used marks to shorten a word. The first word in the deed of grant of the land of Greasby is Ric with a line above the c. This indicates the word has been shortened and should be read as Ricardos, the Latin form of Richard. The deed had been written on behalf of Richard de Rollos (1061-1130), who was giving the land of Greasby on the Wirral to the abbey of St Werburgh in Chester.

As time went on, gradual changes occurred to Carolingian minuscule, making the handwriting more decorative. These changes can be seen when comparing deeds written around 1100 with King John’s (1166-1216) royal charter to the Abbot and monks of Saint Werburgh, Chester, in 1215. Written in Latin and dated 11th January in the 16th year of the reign of King John, the same year the Magna Carta was signed, the royal charter granted the abbey the right of ‘infangthief’, which allowed them to arrest and try thieves caught within the land they leased from the King – all land in those days belonged to the reigning monarch. The charter states this grant was in exchange for the salvation of the souls of the King and of his ancestors.

The medial ‘s’ in Old Roman cursive

The hand that penned the royal charter added flourishes to certain letters, which emphasises their difference from contemporary alphabets. The letter s, for instance, is known as an archaic “long s” and went on to inspire the Eszett (ß) in the German alphabet. The long s, in turn, had derived from the medial s in Old Roman Cursive.

When written as it was in the royal charter, the s could be mistaken for an l to the modern reader. Some scribes added a “nub”, which made it look like a lower-case f. Usually, if a word contained both an s and an f, the writer would refrain from adding the nub to save confusion, for example, ſatisfaction (satisfaction).

The long s began to decline in use during the 19th century, however, before then, several rules had been made about its usage. If the s came at the end of the word, the writer was to use a round s. If the word contained a double s, the long s could replace one or both of the letters, unless it was at the end of the word, for instance, ſinfulneſs (sinfulness) and poſſeſs (possess).

In some words, the long s stuck out like a sore thumb, however, other letters, such as b, h, l and d, had long ascenders too. The descenders, on the other hand, such as p, y and g, were short. Drawing attention away from the tall characters were decorative capital letters, such as the elaborate H in the royal charter. These nuances gradually disappeared as people began to write faster. The fancy letters were reserved for important, official documents.

Quitclaim from Alice le Waleys to Isabel de Cressy of land in Buxton © Derbyshire County Council 2020

During the 1200s, a new type of handwriting script emerged that was unique to England. Now known as Anglicana, the script has been referred to as charter hand, court hand, and cursiva antiquior over the years due to its use in the production of legal documents. Anglicana was written with a thick-nibbed pen and was much quicker to handwrite than Carolingian minuscule, thus allowing scribes to take on and complete more work. This also meant books could be produced more quickly and sold at cheaper prices than those written in a more laborious script.

The ascenders of certain letters were much shorter in the Anglicana script, often being bifurcated (divided) with a curl on either side. Evidence of this can be seen in the quitclaim from Alice le Waleys to Isabel de Cressy, which legally transferred land and property in Buxton, Derbyshire from one woman to the other. These ligatures also leant themselves to joining together two or more letters, which helped the scribe write faster, not needing to remove their pen from the page.

The ascenders of certain letters were much shorter in the Anglicana script, often being bifurcated (divided) with a curl on either side. Evidence of this can be seen in the quitclaim from Alice le Waleys to Isabel de Cressy, which legally transferred land and property in Buxton, Derbyshire from one woman to the other. These ligatures also leant themselves to joining together two or more letters, which helped the scribe write faster, not needing to remove their pen from the page.

By the mid-1400s, the need for a scribe was reducing as more people were learning to read and write. Up until then, the majority of written texts had been in Latin, for which Carolingian minuscule and Anglicana had been purposely invented. As time went on, however, educated people began to write in English, a language which neither handwriting suited, therefore, a new style was needed. By the beginning of the 16th century, a form of handwriting called Secretary hand had been developed specifically for writing English, Welsh, Gaelic and German.

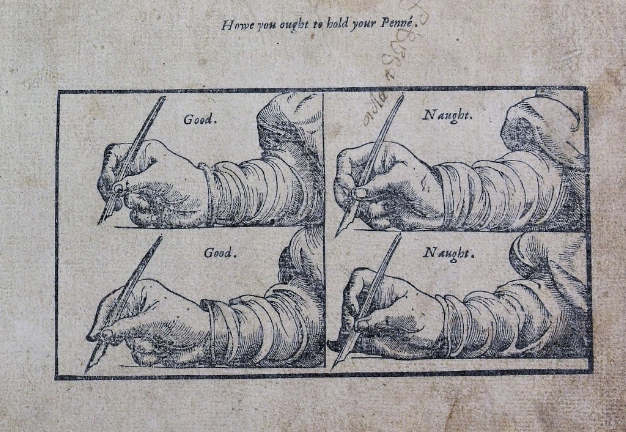

How to hold a pen, from a Sixteenth-Century handwriting manual – John de Beauchesne

Secretary hand was so-called because the majority of the people who wrote it were indeed secretaries or scriveners. John de Beauchesne (c.1538-1620), a Parisian scribe and teacher of penmanship who moved to England in 1565, wrote a book about the new style of handwriting with the rather lengthy title A booke containing divers sortes of hands, as well the English as French secretarie with the Italian, Roman, Chancelry and court hands. Also the true and just proportion of the Capitall Romae set forth by John de Beav Chesne P[arisien] and M[aster] John Baildon. Imprinted at London by Thomas Vautrovillier dwelling in the blacke frieres. The book explained everything from how to write each letter to how to hold a quill pen.

As time went on, this form of handwriting became less precise, making some pieces of writing difficult to read. Scribes of the Medieval period were carefully trained to write neatly and accurately. If they were unable to do this, they found themselves unemployed. By teaching the masses to read and write, penmanship became less focused on style; being able to write was considered more important than presentation.

Detail from a list of Jewels given to Arbella Stuart (1608) © Derbyshire County Council 2020

A list of jewels given to Arbella Stuart (1575-1615) by Lord William Cavendish (1552-1626) is an example of the messier form of secretary hand. Blotted with spilt ink, the list records the “Pearle rings and other things” received by Arbella on “this xxiij daye of february in the fift[h] yeare of the raigne of our Soveraigne Lord King James 1607”. This date, however, is incorrect from a contemporary perspective because, until 1752, 25th March was considered to be the first day of the year. Had the year begun on 1st January, the date would have been 23rd February 1608.

Despite being written in English, albeit with old-fashioned spellings, the script is difficult to decipher. The letter e, for instance, often lacked a full loop, making it look like the letter c. To add to the confusion, the letter r often resembled an x, making the world “pearle” appear to be written “pcaxle”.

Arbella Stuart was the grand-daughter of Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury (c.1527-1608), more commonly known as Bess of Hardwick, who had died ten days previous to the penning of the list of jewels. Bess was the mother of William Cavendish, who was created Baron Cavendish of Hardwick due to his connections to his niece Arbella. Lady Arbella was one of the contenders for the throne after Elizabeth I (1553-1603) but lost out to her cousin James VI of Scotland (1566-1625). As part of the royal family of Scotland, Arbella was expected to marry someone of James VI’s choosing – Ludovic Stewart, 2nd Duke of Lennox (1574-1624) – however, Arbella married her cousin William Seymour (1588-1660) in secret at Greenwich Palace in 1610. Subsequently, Arbella was considered a traitor and was imprisoned in the Tower of London where she died in 1615.

Secretary hand was not the only handwriting style in fashion during the Tudor and Stuart reigns in Britain. By the early 17th century, Martin Billingsley (1591-1622), an English writing-master and handwriting adviser, had identified six common handwriting styles in his book The Pen’s Excellency (1618). These were the Secretary (“the usuall hand of England”); the Bastard Secretary; the Roman; the Italian; the Court; and the Chancery. As early as the time of Henry VII (1457-1509), many writers had begun to use a cursive Italian style, from which the digital italic typefaces have developed. This style was often taught to ladies since they were not expected to write official or important documents, which required secretary hand.

For a while, the Italian style of handwriting was used to emphasise certain words within a document written in secretary hand. Playwrights, for instance, wrote character names and stage direction in an Italian script, and the dialogue in secretary hand. Eventually, secretary hand was phased out and our handwriting today stems from the Italian style.

John de Beauchesne, in his book A booke containing divers sortes of hands, as well the English as French secretarie with the Italian, Roman, Chancelry and court hands… demonstrated the Italian hand. At the time it was written, secretary hand was the preferred style and it took another century before the Italian style became the dominant style.

Derbyshire poet Leonard Wheatcroft (1627-1707) was one of the first writers to fully adopt an Italian style of handwriting. Rather than conforming to the style as drawn out by Beauchesne, Wheatcroft used a mix of styles to form a unique italic handwriting. Born in Ashover, Derbyshire, Wheatcroft was also the village tailor and, later in life, parish clerk and school teacher. Although his poems and autobiography were not published until the 20th century, he was well known as an author and many may have been influenced by his handwriting.

A notebook found in Derbyshire dating to the early 18th century demonstrated the transition from secretary hand to a “Round Hand” based on the principles of Italian handwriting. It is not certain whether the notebook was written by one person, who decided to change their handwriting style, or by two different hands. Nonetheless, the Round Hand is far easier to read with carefully shaped letters that provided the basis for modern handwriting.

By the 1800s, nearly everyone was writing in a style inspired by the Italian hand. Paper was becoming more affordable, as was postage, resulting in an increase of letter writing. The act of writing was no longer an ability reserved for the talented minority, therefore, less attention was paid to the neatness of the handwriting. People began to write faster, resulting in a forward slope that made a mockery of the original “italic” style. To fit more on a page, letter shapes became small and less distinct, making them difficult to decipher.

Clara Palmer-Morewood’s recipe for Bakewell Pudding is an example of this rapid, slanted script. Written in 1837, this barely decipherable recipe disproves the legend surrounding the Bakewell Pudding, which was named after Derbyshire market town of Bakewell. The legend claimed that a maid working in the local White Horse inn during the 1860s made a mistake when making a jam tart. With no time to start the tart from scratch, the pudding was served to the guests who declared it a triumph. Not only has this legend been disproved by Palmer-Morewood’s handwritten recipe, but The White Horse was also demolished in 1803.

Illegible handwriting, such as Clara Palmer-Morewood’s, was unsuitable for professional purposes. Throughout the 18th and 19th century, clerks were required to have excellent handwriting and were responsible for writing up ledgers, wage books and minutes. This was particularly important in factories where everything and everyone needed to be accounted for; an error or messy handwriting could cause many problems.

Lumford Mill in Bakewell, Derbyshire, employed a clerk to document the wages of the employees. The cotton spinning mill was owned by Sir Richard Arkwright (1732-92) who invented the “water frame” in 1769. This was a water-powered spinning frame that helped to speed up the process of manufacturing cotton. Lumford Mill was one of several owned by Arkwright in partnership with Samuel Need of Nottingham (1718-81) and Jedediah Strutt of Derby (1726-97). The wages book is dated 1786 and records in neat columns the types of workers and their pay. From this book, we learn of “Youlgreave pickers”, who picked cotton in the nearby village of Youlgreave, and that the factory operated 24 hours a day.

A sample of a copper plate engraving – George Bickham (1741)

The form of Round Hand used for business and professional purposes became known as Copperplate Script, which is also a style of calligraphic handwriting. Unlike Carolingian minuscule in the 10th century, there was no specific way of writing each letter since each individual’s handwriting would be slightly different. The name of the script refers to the fine nibbed pens used in the 19th century, which resulted in a similar style to engravings or copybooks created using Intaglio printmaking. In this printing method, a thin stylus known as a burin cuts the design into a metal plate.

At school, children often used copy books printed in this manner from which to practice Copperplate writing. The example above shows the handwriting practice of Mary Elizabeth Goodall when she was at Cubley National School in Derbyshire. Each page contained an example of a business receipt, which the students attempted to copy in the same style underneath.

- Pardon of Sir John Gell by King Charles II © Derbyshire County Council 2020

- Charter for the Queen Elizabeth Grammar School in Ashbourne (first page) © Derbyshire County Council 2020

- Marriage settlement between John Franklin and Eleanor Anne Porden © Derbyshire County Council 2020

The journey from secretary hand to Copperplate shows how handwriting developed when writing in English. Documents in Latin, however, were still being produced and there were some notable changes in the style of writing. Carolingian minuscule had led to the development of Anglicana, but the process did not stop there. On the continent, a specific style was used for business transactions in the 13th century, which eventually made its way to England after 1350. Known as Chancery hand due to its use in the royal Chancery at Westminster, all legal documents, patents and Acts of Parliament were written in Chancery hand until 1836.

Several examples of Chancery hand have been preserved in documents dating to the years after the English Civil War, such as the Pardon of Sir John Gell written on the authority of Charles II (1630-85). Sir John Gell (1539-1671) of Hopton Hall in Derbyshire supported Parliament during the war and subsequently became the Governor of Derby in 1643. After his appointment, however, he became disillusioned by Parliament and stepped down from his position in 1646. In 1650, Gell was imprisoned in the Tower of London for not revealing a Royalist plot to the authorities but was pardoned three years later. When Charles II came to the throne, he also pardoned Gell, which was recorded by an unknown scribe in Chancery hand.

Earlier examples of Chancery hand exist, such as the charter for the Queen Elizabeth School in Ashburn. Written in Latin, the charter was adorned with painted figures and motifs including a crown, Tudor Rose, a lion and a dragon. The painting in the top left-hand corner of Queen Elizabeth I is believed to have been produced by the English limner Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619) who worked for the Queen and her successor James I.

This charter, which resulted in the founding of a Free Grammar School, was written with distinctively round letters in a broad nibbed pen. Ascenders, such as on the letters h, d and b are finished off with curls and loops, yet the script remains neat and even. Unfortunately, this evenness can make Chancery hand difficult to read, particularly with the letters m, n, u and i, which all have short vertical strokes. With characters written close to each other, words such as nominanimus become almost impossible to decipher at first glance.

Handwritten documents were often written several times before the final copy was produced. This allowed for any amendments and the correction of errors. The process of writing the final legal document onto official parchment was known as engrossing. Thus, the handwriting style became known as Engrossing hand. Whilst it was extremely similar to Chancery hand, the word spacing made it more legible and was also suitable for writing in English. Engrossing hand was commonly used throughout the 1800s once the legal language switched from Latin to English.

Up until the early 1900s, parents often created marriage settlements for their children and proposed spouses to detail how the assets owned by the bride and groom would be used after the marriage. Documents such as these were written in Engrossing hand, which by the 19th century combined elements of Chancery hand and secretary hand. The round, evenly spaced letters resembled the former, however, some of the letters had a more modern appearance. Like secretary hand, the letter c often looked like an r and an e lost its loop, so it resembled a c.

An example of Engrossing hand discovered by the Derbyshire Record Office is the marriage settlement between the explorer, John Franklin (1786-1847) and Eleanor Anne Porden (1795-1825). Eleanor was John’s first wife, who died not long after giving birth to their daughter, therefore it should not have been too difficult to establish a dowry. Unfortunately, both of Eleanor’s parents had died as had John’s father. As a result, the settlement was signed by Francis Bedford, an executor of Eleanor’s father’s will, and Henry Sellwood (1782-1867), John’s brother-in-law, who incidentally became the father-in-law of Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-92).

By the 1900s, the concept of writing in a particular style was gradually disappearing from education and business. New technologies were being invented to make writing quicker and cheaper, therefore, people no longer felt the need to painstakingly copy Engrossing hand or Copperplate script. Before the 1800s, people had to make their own quill pens from feathers, usually goose, from which they fashioned a nib with a sharp knife. The quill was then dipped into ink and applied to paper. Metal nibs became popular from the mid-1800s, which were longer-lasting, therefore cheaper, than their predecessors.

Before the 19th century, paper was handmade and expensive. People were conscious about wasting paper and went to great efforts to make sure their writing was perfect. From around 1830, paper was being produced by machines, making it more abundant and affordable. Paper was no longer a precious commodity and there was less need to always write in a perfect hand.

Machine-made paper had a different texture to handmade paper, which meant, along with the new metal nibbed pens, the writing process was a lot smoother. As a result, handwriting became broader and less angular, however, this did not always mean it was easier to read. Look at the handwritten note from a governess to her employer from 1896; the writing is barely legible.

Messy handwriting was not an employable trait, however, the invention of the typewriter put an end to this problem. Businesses who had employed clerks for their neat handwriting were now employing secretaries for their typing skills. Handwriting was still considered important and today primary schools continue to have writing lessons. Legal practices and businesses, on the other hand, adopted the typewriter for speed, neatness and cost. Since the invention of the modern computer, there has been no need to use particular handwriting styles. All official documents are typed and it is not often we receive a handwritten letter.

The art of handwriting, for the styles before the 1800s should definitely class as an art, has become a thing of the past. Calligraphy, brush lettering, and the art of typography should not be confused with handwriting because they have their own origins – which would take three articles to explain. We do not get much opportunity to study the handwriting of our ancestors, so next time you come across an old letter or a handwritten book, take time to look at the style of handwriting. Notice the shape of the letters, the ascenders, the thickness of the ink, the uniformity of the words and appreciate this forgotten art.

An Indefatigable Author: or An Idea in the Night George Moutard Woodward © Derbyshire County Council 2020

This blog was based on an online exhibition by the Derbyshire Record Office.

Image sources: Google Arts and Culture, Derbyshire Record Office, and Wikipedia

My blogs are now available to listen to as podcasts on the following platforms: Anchor, Breaker, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts and Spotify.

If you would like to support my blog, become a Patreon from £5p/m or “buy me a coffee” for £3. Thank You!