It is not often that people of the past are able to tell their story in their own words, however, thanks to over 180 surviving treasures, predominantly of a written nature, the people of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms narrate their history in an exhibition at the British Library. Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War explores over 600 years through surviving books and remarkable finds from excavations around the country. Although many items have not survived the passing of time, beautifully illuminated manuscripts illustrate the ways of life, wars, religions and the beginnings of the English language.

The Anglo-Saxons were migrants from Northern Europe who arrived in England during the 5th and 6th centuries. These Germanic-speaking people arrived in stages and are now combined into three groups: the Saxons, the Angles and the Jutes. The term “Anglo-Saxon” did not actually appear until the late 8th century when the bishop of Ostia, travelled to England to attend a church meeting, reporting back to the Pope that he had been to ‘Angul Saxnia’.

The exhibition begins with two of the earliest remnants of the early settlers of the 5th century. Rather than exposing the way they lived, it explains how they dealt with their dead. Referred to as a Spong Man, an anthropomorphic urn lid reveals that cremation was their predominant custom for disposing of bodies, as does the cremation urn displayed beside it. Found during excavations at Spong Hill, North Elmham, Norfolk, Spong Man is one of many pieces of pottery from the largest known Anglo-Saxon cremation cemetery. The urn, however, was one of over 1800 found in an early medieval cemetery at Loveden Hill, Lincolnshire. It is believed that some of the runes carved into the surface spell out a female name, however, it is unknown as to whether this was a woman of high status. Also, it cannot be sure that the Spong Man indicates the wealth or importance of the owner.

It is likely that these cremation objects would have been a part of a pagan ceremony. Although the Romans had introduced Christianity to England prior to the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons, the new settlers brought their pagan gods with them, for example, Woden, who may be synonymous with the chief Norse god Odin. Christianity returned to Britain in the 7th century with missionaries from Rome visiting with the intention of converting kings. England was made up of several smaller kingdoms and it is believed that King Æthelberht of Kent was the first to be converted.

- The St Augustine Gospels

- The Lindisfarne Gospels

- The Lindisfarne Gospels

- St Cuthbert Gospel

The British Library displays some of the oldest, handwritten documents in existence, including the earliest letter sent from England and the earliest English charter. In the beginning rooms of the exhibition, however, the majority of the documents and manuscripts are religious. Along with Christianity came religious books, which were copied numerous times, each area having its own version. To begin with, only the Gospels were copied, which, although there are only four, would have taken a long time to write out by hand. On display are the St Augustine Gospels, the earliest Durham Gospel Book, the Echternach Gospels, the St Chad Gospels, the Bury Gospels, the Trinity Gospels and the Grimbald Gospels, to name a few.

All of these Gospels are rare and it is lucky that they have survived as far as the 21st century. Many have been lost during wars and invasions or during the dissolution of the monasteries in the 16th century. Others have been destroyed by fire, for example, during the Cotton Library fire in 1731 once owned by Sir Robert Bruce Cotton (1571–1631), to whom the British Library collection is indebted. In some instances, parts of books were salvaged, as can be seen in the exhibition, although rather singed at the edges.

Sir Robert Bruce Cotton’s library was the richest private collection of manuscripts ever accumulated, surpassing even the Royal Library. One of the most well-known treasures in his collection, at least by name, was the Lindisfarne Gospels, now owned by the British Library. It is believed that these were the first English translation of the Gospels and remain to be the most spectacular manuscript to survive. It is believed that they were written and illustrated by Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne, also called Holy Island, off the northeast coast of England between 698-721 AD. It contains all four Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John; as well as other traditional sections included in medieval texts, such as letters of St Jerome. As well as being an example of Anglo-Saxon religious texts, it is a phenomenal work of art with numerous illuminations, illustrations and coloured patterns on every page.

Another notable manuscript that may hail from Lindisfarne is the St Cuthbert Gospel. This was found in the coffin of St Cuthbert (d. 687) the bishop of Lindisfarne when it was opened at Durham Cathedral in 1104. It is the oldest European book with its original binding intact and is thought to have been produced during the 8th century. Containing only the Gospel of St John, the small book has a wooden cover wrapped in red goats skin, decorated with a geometric pattern. In the centre of the front cover, a motif of a stylised vine sprouting from a chalice, which mirrors Mediterranean Christian imagery, represents the well-known verse “I am the vine, you are the branches.” (John 15:5)

Codex Amiatinus

Of all the religious texts in the exhibition, there is none as impressive as the Codex Amiatinus. This is the first complete Bible to be written in Latin, containing both the Old and New Testaments. Originally, three were produced in the early 8th century but only one survives in full.

Those who see the Codex Amiatinus on display at the British Library will be impressed by its remarkable size. Made from 1030 pages, 515 of which have been identified as animal skin, it is over 1 and a half feet (49cm) high with a weight of over 75 pounds (34 kg). Historians initially believed it was an Italian book, however, it has since been proven to have been produced in England during the 8th century. In 716, Abbot Ceolfrith took this volume to Rome, intending it as a gift to the shrine of Peter the Apostle. Since then, until this exhibition, it has been looked after at the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence.

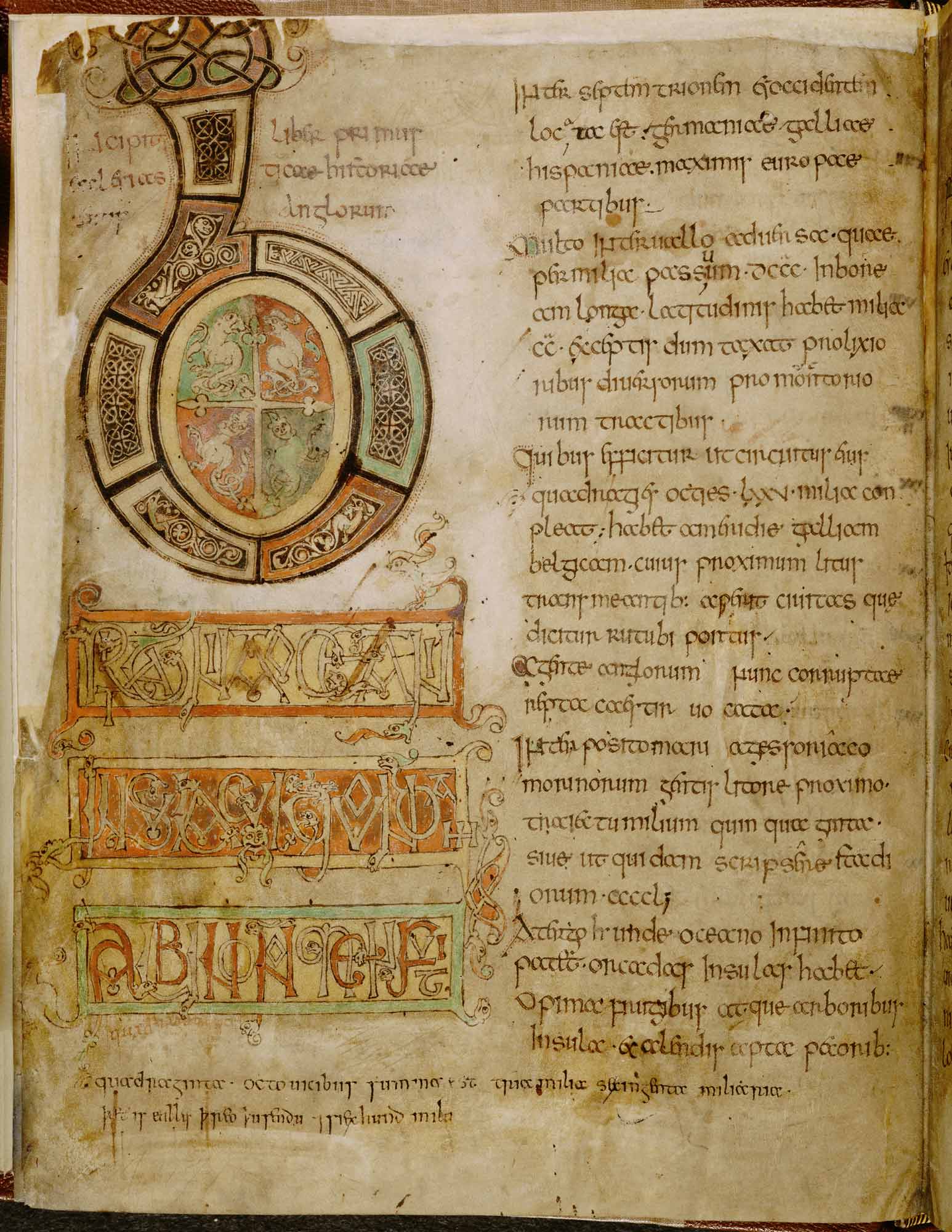

- Bede, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

- Bede, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

- Bede, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

For knowledge about the first half of the Anglo-Saxon period in England, historians rely strongly upon one particular manuscript. This is the Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, or Ecclesiastical History of the English People, completed by the Venerable Bede in 731. Bede (673-735), also known as St Bede, was the greatest scholar of the time, who produced a number of works on a variety of subjects. Due to this particular publication, of which the British Library has a few examples, Bede is often regarded as the father of English history.

Modelled on the Ecclesiastical History by the Greek Christian historian Eusebius of Caesarea (260/265 – 339/340 CE), Bede tells the story of the development of Christianity in England beginning with the arrival of St Augustine in Kent in 597. He also explains the attempts to convert the kings of other areas, including Mercia, Sussex and Northumbria, thus painting a picture of the landscape and kingdoms of Britain.

Bede acknowledges that he referred to other sources (now lost) to write about the years long before he was born, however, no one can be certain of the accuracy of his account. Whilst Bede was ahead of his time in stating that the world was not flat but rather a globe, he also assumed the Earth was the centre of the universe. Nonetheless, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History is one of the only written evidence of life during the Anglo-Saxon period, and it is thanks to the survival of his work that knowledge of that era can be ascertained.

- The Alfred Jewel

- Æthelstan presenting a book to Saint Cuthbert

- The law-code of King Æthelberht of Kent

Bede’s Ecclesiastical History also notes the changes in fortunes of the English kingdoms. By the mid-600s, Northumbria, which encompassed a large part of northern England, was the most powerful Anglo-Saxon kingdom. This period of time is referred to by the British Library as Northumbria’s “Golden Age”, however, by the early 8th century, things were beginning to change. With an aspirational king, Æthelbald, the kingdom of Mercia displaced Northumbria from its position as most powerful. Æthelbald went as far as to name himself “king of Britain”, although he did not have control of the whole of the British isle.

Mercia continued to sustain its supremacy throughout the 8th century, particularly during the reign of King Offa from 757 until 796. Offa was responsible for the building of a dyke fortification along the border of Wales, to keep the Welsh tribes out of England plus conquered other parts of the country, including Kent, Sussex and East Anglia. He also reintroduced the coinage system to Britain, such as the gold dinar and silver penny the Library has on display.

Unfortunately, the great efforts of King Offa were threatened by rival kingdoms and the hostile Vikings from Scandinavia who had begun raiding England in the 790s. As a result, much of East Anglia, Mercia and Northumberland became under the rule of Guthrum, the leader of the Danes. Nevertheless, the West and South Saxons consolidated their power under the leadership of King Alfred, perhaps one of the most recognised of the Anglo-Saxon kings – mostly due to the legend that he burnt some cakes! A jewel belonging to the king is on display in the exhibition. It is inscribed “ÆFLRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN” which translates as “Alfred ordered me to be made.”

During Alfred the Great’s reign (871-899), a peace treaty was agreed with the Vikings that England would be divided into two parts: the north and east would belong to them and the south and west to the Anglo-Saxons. At this time, Guthrum was persuaded to convert to Christianity and took the name Æthelstan at his baptism.

Æthelstan was also the name of Alfred’s grandson who reigned from 924-939. Initially, he was the king of the Anglo-Saxon section of the country, however, after the death of the Viking ruler in 927, he took back Northumbria and claimed land in south Scotland, making him the first “king of the English”. In Bede’s manuscript Life of Saint Cuthbert, Æthelstan is illustrated presenting a book to the saint. This is the earliest surviving representation of a king, thus the first royal portrait.

Whilst the Codex Amiatinus mentioned earlier is the most impressive manuscript in the exhibition, it is without a doubt that the Ruthwell Cross is the most remarkable non-book object. Although some may be disappointed that it is a digitally cut replica rather than the real thing, it is one of the best examples of Hiberno-Saxon art – a style that thrived after the departure of the Romans.

The original, found in the village of Ruthwell, Scotland, is a stone cross that reaches over five metres in height and is elaborately carved with scenes from the life of Christ. Although there are some debates about what these scenes are, most agree that they show characters such as Mary and Martha, Mary Magdalene, the Virgin Mary and Christ himself. One carving may represent one of Jesus’ miracles, the healing of blind Bartimaeus (Mark 10:46-52).

Believed to have been made in the 8th century, the cross features an unusual mix of Latin and Old English runes. Whilst it is odd to find both languages on the stone, the use of runes on a Christian monument was extremely rare. The runes spell out of a version of The Dream of the Rood, one of the oldest surviving Old English poems, which tells the story of the crucifixion of Christ from the perspective of the tree cut down to make the cross to which Christ was nailed. A written copy of this can be found in the late-10th-century Vercelli Book displayed nearby.

- Beowulf

- Old English Illustrated Herbal and other medical remedies

- Diagram of the planets’ orbits, from Isidore of Seville’s De Natura Rerum

“At the present moment, there are the languages of five peoples in Britain … English, British, Irish and Pictish, as well as Latin.”

– Bede

Religious books were not the only genre written during the Anglo-Saxon period. As the English language developed, more people were learning to read and write. Poetry was inspired by the multicultural and multilingual societies and made easier to write with the introduction of the Roman alphabet. Although parchment was expensive, people were able to practice writing on whale-bone tablets. These were covered in wax and scratched into with a bone stylus.

In one display cabinet is an example of an Anglo-Saxon glossary, a precursor of the modern dictionary. Unlike the older books in the collection, the Old English language is written in the new alphabet and is, therefore, legible. The first word on the opened page is “anser”, which is the Old English for “goose”. This is followed by “anguila” meaning “eel”.

Surviving in full, although undated, Beowulf is the longest epic poem written in Old English. Judging by the handwriting, it is thought to have been written in the late-10th or early-11th century, however, its author remains unknown. Consisting of more than 3000 lines, Beowulf tells the story of its eponymous hero as he battles with a monster named Grendel and a dragon guarding a hoard of treasure. The manuscript in the British Library is extremely fragile as a result of being exposed to the flames of the fire at Cottons Library and poor handling during the following years. A brief audio clip of Beowulf is available to listen to during the exhibition.

As well as literature, there was a growing interest in the natural sciences, although no Old English word exists for this topic. It was a branch of scholarship that combined religion with the order of the universe. As early as the 7th century, people were looking up at the stars and contemplating what was out there. In De Natura Rerum (On the Nature of Things), Isidore of Seville (d. 636) sought to combat superstition by offering explanations for natural phenomena, for instance, the planets of the solar system, as shown in one manuscript. This shows the ‘position of the seven wandering stars … called planets by the Greeks’ – the moon, Mercury, Lucifer, ‘which is also called Venus’, Vesper (or Mars), Foeton, ‘which they call Jupiter’, and Saturn – which all rotate around the Earth.

Most scientific texts were not written in England but imported from the continent and translated into Old English. These included books of remedies, particularly herbal remedies, which was the basis of medieval medicine. An example shown in the exhibition is lavishly illustrated with paintings of plants and animals, although these are not accurate enough to identify specific species.

“Books are glorious … they gladden every man’s soul.”

Solomon and Saturn, 10th Century

Naturally, books are the prominent feature of exhibitions at the British Library and it is through these that the major changes of Anglo-Saxon Britain can be determined. Religion remained a key theme throughout the exhibition, starting with the various versions of the Gospels as previously mentioned. After the conversion of the kings in the 7th century, the country became a deeply religious area, which helped to influence and strengthen the power of future kings.

King Edgar (959-75), the great-grandson of Alfred the Great, used the rising religious standards to his benefit. In control of the entire kingdom of the English, Edgar took the opportunity to reform and improve religious standards. Adopting the Rule of Saint Benedict written in the 6th century by Benedict of Nursia (480–550), Edgar reformed the way abbeys and monasteries functioned, for instance, separating monks and nuns into different establishments. As a result, the monasteries and nunneries began to prosper and become quite powerful.

“Nothing has gone well for a long time now … there has been harrying and hunger, burning and bloodshed.”

– Archbishop Wulfton

Whilst England was a wealthy and organised kingdom during the reign of King Edgar, its time of prosperity was not to last. The 980s brought more Viking raiders to the country and warfare was once again underway. As Archbishop Wulfton noted in The Sermon of the Wulf (1009), of which an audio excerpt is available, things were not going well for the Anglo-Saxons. By 1016, England had been conquered by Cnut (990-1035), the King of Denmark, who expanded his empire to include Norway and parts of Sweden. Cnut was a ruthless ruler and disposed of many of the aristocrats and governors of England, however, he allowed previous English laws to continue and supported the Church. He is most famous for the disputed tale that he set his throne on the seashore and commanded the tide to turn, which, of course, it did not.

After Cnut’s death in 1035, two of his sons, Harold and Harthacnut, had short reigns, eventually leading to the return of the royal English bloodline in the form of Edward the Confessor (1003-1066), the son of Aethelred II. Most people will know about the reign of King Edward, Harold Godwinson, the Battle of Hastings and William the Conqueror (1028-1087), and the Library mentions very little about the period.

The Coronation of William the Conqueror brought the kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons to an end, however, the exhibition could not close without the inclusion of one of the most famous books in history. At the end of 1085, William ordered a detailed survey of his kingdom, which, completed seven months later, revealed the names of landholders, settlements and assets of England. Titled the Domesday Book, a total of 31 counties were accounted for and 13,418 settlements recorded. A brief video provided by the British Library explains the importance of this book and how it offers a snapshot of the wealth and landscape of the late Anglo-Saxons.

The British Library has made excellent use of all the surviving books to paint a mental picture of English life between the 6th and 12th century. Amongst the books are remains of ancient artefacts discovered during excavations, for instance, the Burnham and the Staffordshire hoards.

Dubbed “by some distance, the most significant exhibition in London,” by the Evening Standard, Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms surpasses expectations. Rather than being a display of books that most people can’t read due to the Old English language, it is a concise history of the Anglo-Saxons and an insight into how the world we experience today stems from the events of so many centuries ago. The exhibition will appeal to a wide range of people from academics to those with a little interest in English history, although, it may not be overly exciting for young children.

Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms will remain open until Tuesday 19th February 2019. Full price tickets cost £16, however, concessions are available. Members of the British Library can view the exhibition for free.

My blogs are available to listen to as podcasts on the following platforms: Anchor, Breaker, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts and Spotify

If you would like to support my blog, become a Patreon from £5p/m or “buy me a coffee” for £3. Thank You!