Until 8th March, the British Museum is celebrating the legend of Troy, which has endured for over 3000 years. With ancient artefacts and more recent artworks, the museum tells the story of the Trojan War from its beginning to its end, followed by the fateful journey home of one of the Greek heroes. Whilst this story may be purely mythical, the British Museum also explores the true existence of Troy, which was discovered during the 19th century.

Bust of Homer

Many people know some of the stories surrounding the Trojan War, which have been told for over 3000 years. Initially spread by word of mouth, it is generally believed the story was put together by the Greek poet Homer as early as the 8th century BC. There are some arguments that Homer never existed and the stories were compiled by several authors, however, the final result had been published under Homer’s name in two volumes, the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Written in a dactylic hexameter – a form of poetry – the Iliad spans approximately fifty-one days of the ten-year Trojan War on the coast of Anatolia, now known as northwestern Turkey. The city of Troy was under siege by a coalition of Greek states as revenge for the abduction of Helen of Sparta.

The war began shortly after the wedding of the sea-goddess Thetis and Peleus, the king of Thessaly. All the Greek gods and goddesses were invited to the ceremony except for Eris, the goddess of discord. Angry at being left out, Eris turned up unannounced and threw a golden apple into the crowd of party-goers. The apple bore the inscription “to the most beautiful” and three goddesses: Aphrodite, Athena and Hera, believed it was intended for them.

- The Judgement of Paris

- The Three Goddesses

The goddesses appealed to Zeus, the king of the gods, to decide who was the most beautiful. Reluctant to get involved, Zeus instructed Paris, the visiting Trojan prince, to make the decision. Paris’ judgement was by no means fair because, before he could make a decision, Aphrodite the goddess of love, promised Paris the love of the most beautiful woman on earth if he chose her as the winner of the competition. Naturally, Paris chose Aphrodite.

After the wedding, Paris visited the Greek state of Sparta where he met Helen, the woman Aphrodite promised him. Unfortunately, Helen was already married to King Menelaus, so when Paris returned to Troy with Helen, Menelaus was determined to get his wife back. Agamemnon, the king of Mycenae called together a huge fleet of Greek heroes to sail across the Aegean Sea in support of his brother Menelaus. Thus, the Trojan War began.

The Iliad begins in the middle of the plot after the Greeks have been attempting to breach the strong walls of the city of Troy for nine years. Although they had not managed to enter the main city, the Greeks had raided surrounding towns belonging to Troy and taken many inhabitants as prisoners. Amongst these prisoners was a young woman named Briseis who was given as a prize of honour to the Greek Hero Achilles, son of Thetis.

King Agamemnon’s prisoner was Chryseis, the daughter of a Trojan priest of Apollo. The Trojan’s offered money in return for the girl, however, Agamemnon refused. So, the priest prayed to Apollo who sent a plague over the Greek army until they returned Chryseis to her father. In retaliation, Agamemnon took Briseis from Achilles, causing the Greek hero to, quite simply, have a huge sulk.

The Death of Patroclus

Furious with Agamemnon, Achilles refused to fight in the war and asked his mother, Thetis, to make the Greeks realise how much they needed Achilles on their side. In the fighting that followed, the Trojans began to get the upper hand. In desperation, Achilles’ friend and potential lover Patroclus entered the battle disguised as Achilles in an attempt to raise the morale of the Greek soldiers. It worked; both the Greeks and the Trojans believed Patroclus was Achilles, however, this put him in mortal danger when he was targetted by the Trojan prince Hector.

When Achilles heard that Hector had killed Patroclus, he fell into a state of grief-stricken rage. Despite knowing the prophecy that stated if Hector died, Achilles would soon follow, the Greek hero returned to the battle site clad in new armour forged by the god Hephaestus. In a blind rage, Achilles killed Hector, tied the corpse to the back of a chariot, and proceeded to desecrate the body by dragging it around the battlefield for several days. Taking pity on Hector’s family, the gods protected Hector’s body from damage until Achilles could be persuaded to hand the corpse over to King Priam for a traditional Trojan funeral.

Achilles killing the Amazons

This is where the Iliad finished, however, the war was by no means over. Troy called upon its allies for support, but the Amazons and Ethiopians were no match for Achilles’ strength. Whilst Achilles continued to fight, he knew as a result of Hector’s death, he was destined to die soon.

When Achilles was a baby, his mother dipped him into the waters of the River Styx to make him invulnerable to injury. Unfortunately, the ankle from which she dangled him did not enter the water, therefore, Achilles was vulnerable in this area. It was in this precise spot that an arrow shot by Paris hit Achilles, fatally wounding the Greek Hero. Despite their best warrior dead, the Greeks continued to fight.

The Greeks won the war thanks to an ingenious invention by Odysseus, the king of Ithaca. He encouraged the Greek army to build an enormous wooden horse, which they placed outside the walls of Troy as a decoy peace offering. Believing the Greeks had given up the fight, the Trojan’s accepted the gift and brought it into the city, unaware that it housed some of the best Greek fighters. Once through the walls, the Greeks crept out of the horse and attacked the city from within, eventually destroying Troy and killing King Priam and Hector’s son, Astyanax. Only one member of the royal family survived, Aeneas, the son of King Priam’s cousin, whose survival story is told in the Aeneid by Publius Vergilius Maro (Virgil).

Troy fell, the war ended and Helen was reunited with her husband, however, this was not the end of the story for the Greeks. The gods were angry at the sacrilegious atrocities committed by the Greeks during the war and decided to teach them a lesson by making their journey home rather difficult. No one’s journey was as bad as Odysseus whose ten-year attempt to return home is recorded in Homer’s Odyssey.

“Tell me about a complicated man.

Muse, tell me about how he wandered and was lost

when he had wrecked the holy town of Troy …”

– Odyssey, Homer, 700 AD

Initially, twelve ships, including one belonging to Odysseus, were driven off course by the storms caused by the angry gods. As a result, Odysseus and his men sheltered in the land of the Lotus-Eaters. These were a race of people whose primary food source was the lotus fruits, which had a narcotic effect on foreigners. Naturally, Odysseus’ men accepted food and hospitality from the peaceful natives and forgot that they were on their way home from Troy. It was only through physical force that Odysseus managed to get his men back onto the ships.

Since it was impossible to bring an endless supply of food on a ship, Odysseus soon had to make another stop. On an uninhabited island – or so they thought, Odysseus and his men discovered a cave full of meat and cheese. Before they could return to the ship, the cave’s owner, a cyclops named Polyphemus, arrived and sealed the entrance to the cave. Trapped inside, Odysseus had to think quickly and introduced himself to the cyclops as Nobody. Odysseus persuaded Polyphemus to drink excessive amounts of wine until the cyclops fell asleep. Taking the opportunity, Odysseus used a wooden stake to blind the one-eyed creature, who woke up with a shout. Other cyclopes arrived on the scene to find out what the fuss was about but soon went away when Polyphemus told them “Nobody attacked me.”

Hiding under the underbellies of Polyphemus’ sheep, Odysseus and his men escaped the cave when the cyclops unsealed the entrance in the morning. They could easily have sailed away and gone straight home, however, Odysseus foolishly boasted about defeating the cyclops, revealing his name in the process. Polyphemus prayed to his father, Poseidon the god of the sea, to curse Odysseus to wander the seas for ten years, losing all his men in the process.

Odysseus’ next stop was the island of Aeolia where Aeolus, the keeper of the winds resided. He gave Odysseus a leather bag containing all the winds except for the one that would blow their boat home. With instructions not to open the bag, Odysseus and his men set off towards Ithaca, however, whilst Odysseus was asleep, his men fell to temptation and opened the bag, releasing all the winds. As a result, the boat was blown off course, taking them even further away from home.

Following this, Odysseus and his men met with several disasters. The first occurred on the Laestrygonians’ Island where cannibalistic giants feasted on the majority of the men. The survivors sailed on to the island of Aeaea, where a witch-goddess Circe, daughter of the sun-god Helios turned all but Odysseus into pigs. Although Odysseus forced Circe to return his men to human form, her charm caused him to remain on the island for an entire year.

Odysseus managed to avoid disaster as they passed the land of the Sirens. The Sirens were dangerous creatures who lured sailors to their deaths with their beautiful songs. Odysseus instructed his men to plug their ears, however, he wished to hear the music. Odysseus tied himself to a post so that he could not be tempted to follow the sounds of the Sirens’ voices. Whilst no incident occurred with the Sirens, there was danger just around the corner. The ship had to pass between two creatures: Scylla, a six-headed monster, and Charybdis, a whirlpool. Although they successfully avoided Charybdis, Scylla managed to snatch up six men.

The next island Odysseus and his remaining men visited was Thrinacia. Due to a storm, they were unable to leave the island for several days, causing them to use up all their provisions. Hungry, Odysseus prayed to the gods, however, his desperate starving men hunted down some cattle to feast upon. These cattle, however, turned out to be the sacred cattle of Helios, the god of the sun. As a punishment, the next time Odysseus and his men took to the sea, the gods caused a shipwreck, which only Odysseus survived.

With no means of getting home, Odysseus found himself washed up on the island of Ogygia, where he was kept captive by the nymph Calypso. After seven years of homesickness, Zeus compelled Calypso to release Odysseus so he could eventually return home.

Penelope mournfully waiting for her long-absent husband

For ten years, Odysseus’ wife Penelope waited patiently for her husband’s return. Believing him to be dead, many suitors tried to worm their way into the household. Penelope fended them off by saying she would only marry one of them after she had finished her weaving. Each day, she sat weaving and every night she undid the progress she had made, thus the work would never be finished.

On returning home, Odysseus found his home had been taken over by 108 young men. Disguised as a beggar, Odysseus killed the leader of the suitors and revealed himself to his wife. Finally, the Trojan War got its happy ending.

It is not certain whether there ever was a Trojan War and Odysseus’ journey home seems even less probable. For hundreds of years, people assumed it was a myth, a story for entertainment purposes. Nonetheless, this did not stop people from trying to locate the city of Troy. Believed to be situated in Anatolia – northwest modern-day Turkey – pilgrims visited the area, believing they were travelling the paths of their ancient heroes.

Heinrich Schliemann by Sidney Hodges

An English expatriate, Frank Calvert (1828-1908) believed he had located the site of Troy on a mound at Hisarlik, the remains of an ancient city near Çanakkale in Turkey. Seven years later, when Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890), a German pioneer of archaeology, arrived, Calvert quickly persuaded him to investigate the area. What they discovered was the remains of the mythical city of Troy. Although Calvert helped with the excavation, it was Schliemann who took the accolades.

Between 1870 and 1890, Schliemann’s excavations revealed more and more about the real city of Troy. It is estimated people first settled in the area around 3000 BC during the Early Bronze Age. For around four thousand years, people lived in Troy until it was abandoned in 600 AD. Schliemann’s findings and those of archaeology teams that followed him record how people lived during this lengthy period.

Life in Troy has been categorised into nine phases with Troy I being the earliest and Troy IX the last. Troy I was only a small village but by the time Troy II was established between 2500 and 2300 BC, the city had strong walls encircling a citadel, although still rather small. Being on the Dardanelles strait, Troy would have been in prime position for trading, which may explain its gradually increasing size.

By the Late Bronze Age (1750–1180 BC) Troy had a larger citadel with stronger, sloping walls, some of which can still be seen today. As well as access to the trade route, surrounding Troy was agricultural land, which was used to keep animals, particularly sheep and grow crops. Evidence of horses in the area have also been unearthed, which links to the Trojan prince Hector in the Iliad, who was described as a horse-tamer.

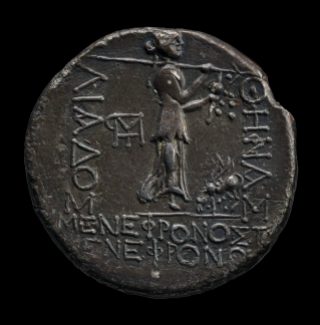

Troy was destroyed at the end of the Bronze Age (1180 BC), which some have attributed to the Trojan War. Other cities in the Mediterranean, however, were also destroyed for reasons unknown, which puts the specific Trojan War into question. Homer did not live, if he ever existed, until the 8th or 7th century BC, by which time Troy had been rebuilt and renamed Ilion, which is the name Homer uses in the Iliad.

Troy, or Ilion, flourished once more. Although it was not as important as other cities in the ancient world, it was a populous city for hundreds of years. It seems strange that a large city could ever be “lost”, however, by the 6th century AD, the population had dwindled and unused buildings crumbled away. Any evidence of Troy’s existence was eventually covered by debris until all that remained was the hill-shaped mound now known as Hisarlik.

Schliemann was convinced Troy II was the ancient Troy or Ilion mentioned by Homer and, therefore, the site of the Trojan War. Archaeologists today, who are still excavating the area, date Troy II to the Early Bronze Age, which is too early for the war, nor does it contain any physical evidence of combat.

Although the mythical Troy has yet to be proven or disproven, life in the city has been discovered and documented, beginning with the 100 or so items Schliemann brought to England for an exhibition at London’s South Kensington Museum (V&A) in 1877. Amongst the items were “face pots” that appeared to have eyes and may have, as Schliemann believed, been idols of the goddess Athena. Many other pots were also in the collection, some with three “legs” and one big enough to store enough grain to feed a small family for a year.

Rather than ending the exhibition here with the half-successful search for the site of the Trojan War, the British Museum returned to the myths with a selection of artworks that explore how artists have interpreted the stories over the past millennium. Authors have also used the Trojan myths as the basis of their stories, for instance, William Shakespeare‘s Troilus and Cressida and Edward Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (1590): “For noble Britons sprang/from Trojans bold,/And Troynovant was built/of old Troy’s ashes cold.”

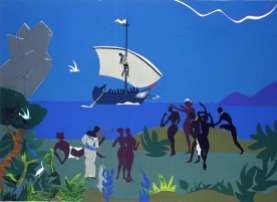

Even though artists have chosen to depict the same scenes, for instance, the sirens, their outcomes are very different. Take, for example, African-American artist Romare Bearden’s (1911-88) The Siren’s Song, which shows Odysseus tied to the mast of his ship in the background. In the foreground, the sirens are dancing in human form, attempting to lure Odysseus to his death. In Greek mythology, sirens were represented as part human and part bird, however, Bearden portrayed them as fully human.

Herbert Draper (1863-1920) is another artist who altered the appearance of the sirens. In Ulysses and the Sirens – Ulysses being the Roman name for Odysseus – Odysseus is once again tied to the mast, however, sirens in the form of mermaids are attempting to climb onto the ship. Mermaids are half-human, half-fish and may have been inspired by the Greek sirens. In folklore, mermaids also lure sailors to their deaths.

Whilst heroes tend to be portrayed during their prime, a few artworks at the British Museum reveal the vulnerable side of the great men. Hector was one of Troy’s best fighters and it was a great loss when he was killed in battle by Achilles. British artist of Huguenot descent Briton Rivière (1840-1920) painted Hector lying dead, face-down in the sand. As the Iliad tells us, Achilles dragged Hector’s body around the battlefield for several days, however, the gods protected the corpse from damage. In Rivière’s painting, Hector’s muscular body looks as pure as it would had he been alive.

Achilles heel is usually regarded as his only vulnerability, however, his emotions also get the better of him. Firstly, his anger causes him to stubbornly refuse to fight but when Patroclus is killed, his anger turns to grief followed by rage, which causes him to join the battle and go after Hector. The Swiss painter Henry Fuseli (1741-1825) produced a quick sketch of Achilles lamenting the death of his best friend. Achilles collapses over the body of Patroclus, which is an action that many would deem unmanly. Fuseli, on the other hand, admired Achilles and the other Greek heroes for their authentic emotions.

Helen of Troy, the most beautiful woman in the world, was a popular topic for artists. Since no one knows what Helen looked like, artists have portrayed their own perceptions of beauty. William Morris (1834-96) drew Helen as the Flamma Troiae (Flame of Troy) with long, flowing blonde hair. Although she supposedly ignites passion in men, she demurely looks down as though innocent of the effects of her beauty.

Evelyn De Morgan’s (1855-1919) version of Helen, however, is much more enticing. Aware of her beauty, golden-haired Helen looks into a hand mirror, absorbed with her own appearance. The contours of her dress reveal her slender legs and her bare arms are something women of the past would not have dreamed of showing in public.

Helen’s Tears – Edward Burne-Jones

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), on the other hand, took a different approach to Helen. Rather than focus on her beauty, Burne-Jones thought about how the war would have affected her. In his tiny watercolour, Burne-Jones shows Helen consumed by guilt about the destruction of Troy. Wearing dark clothing, she holds her hands to her face whilst Troy burns around her. Although the war was not her fault, she is taking the blame for the outcome, for it is for her that the Greeks came to destroy the city. The crown atop her head indicates Helen’s importance in the story. She is not just a beautiful woman, she is a queen. Paris may have taken Helen because she was the most beautiful woman in the world but the Greeks want her back because she belongs to them as the wife of Menelaus.

Contemporary artist Eleanor Antin (b.1935) recreated the Judgement of Paris in a humorous, modern, photographic manner. The male models represent Zeus and Paris who are looking at the three goddesses whilst trying to decide which of them is the most beautiful. Athena, the goddess of warfare amongst other things, holds her rifle aloft, whilst Aphrodite in magenta and purple strikes a tempting pose. Presumably, the winged child hugging Aphrodite is Eros, known as Cupid in Roman mythology. The most humorous depiction of a goddess is Hera, goddess of the home, who dressed as a 1950s housewife, holds a vacuum cleaner in one hand. Helen, who is dark-haired in this version, sits to the side, thoroughly annoyed that she is being treated as a possession rather than a human being.

William Blake’s (1757-1827) The Judgement of Paris is more in keeping with other artists’ version of the scene. The three goddesses, all of them naked, stand in front of Paris as he hands the apple to Aphrodite. In the sky above, a demonic figure, possibly Eris the goddess of discord, indicates the destruction that is yet to come.

The exhibition ends with two shields. Since Roman times, people have attempted to recreate Achilles’ shield, which as no one knows what it looked like, has been a virtually impossible task. According to Homer, the shield was forged by the god Hephaestus and, therefore, was better than any man-made shield. In 1822, John Flaxman (1755-1826) designed a shield that took inspiration from ancient works of art. Using clay to make a model, Flaxman included scenes from the Trojan War on the shield, which was eventually gilded in silver.

The other shield is a contemporary installation by Spencer Finch (b.1962). Made from fluorescent lamps positioned in a radiating circle, Finch created this shield after visiting Troy and feeling moved by the mythical stories. Whilst this particular shield would be useless in battle, it shows the story of the Trojan War is still fresh and popular in the 21st century. Whether myth or reality, the story continues to live on.

Troy: Myth and Reality is on display at the British Museum until 8th March 2020. Tickets are £20, however, under 16s can attend for free when accompanied by a paying adult.

My blogs are now available to listen to as podcasts on the following platforms: Anchor, Breaker, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts and Spotify.

If you would like to support my blog, become a Patreon from £5p/m or “buy me a coffee” for £3. Thank You!

What a tour de force. So much information included here. Well done once again for such an informative piece of work..

This was such a joy to read, thank you Hazel. I loved the retelling if the two stories and with your mastery of words and the illustrations you chose to add I found the whole reading experience a delight.

Thank you for sharing with us.

Pingback: The Finest of the Fine | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Beside the Sea | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Lady Jane Franklin | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Dealing With Cards | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Feminine Power | Hazel Stainer

Pingback: Alexander: The Making of a Myth | Hazel Stainer